Film music can be hard to get a handle on… and intentionally so. The music is a part of the whole, not the whole itself, and as such it's supposed to point elsewhere, or simply fade into the background. The music isn't the thing to look at, but the wallpaper behind the thing you're looking at, and what is there to say about wallpaper, anyway?

Broadcast's soundtrack for the experimental film Berberian Sound Studio certainly fits the aural wallpaper mode. It clocks in at 37 minutes and 39 tracks, each brief song fitted with a provocative, metal-worthy title like "Burnt at the Stake," "Collatina, Mark of Damnation," "Here Comes the Sabbath, There Goes the Cross" or "Found Scalded, Found Drowned." This isn't metal—it's drifting ambience, and the many short songs simply wander gently into one another, equal part fey woodland glade and ominous organ church service. I haven't seen the film, but just from listening, you'd have to assume it involves scene after scene of fairies quietly sacrificed on altars made of keyboards.

Occasionally a riff or motif will rise out of the worshipful miasma. "The Sacred Marriage" has multi-tracked ghostly voices and a funky beat that seems to have strolled in from a blaxploitation film before it shame-facedly dissolves into glockenspiel-like bells and choral dissonance. "A Goblin" is 30 seconds of truly impressive gurgling and gibbering, silenced by a whip crack and a rising wind that is cut off abruptly. "Mark of the Devil" sounds like a robot having some sort of catastrophic sine-wave-describable bowel-event while Gregorian chanters cheer him on through a busted radio. "The Equestrian Vortex" is much more vortex than equestrian; a kind of march with echoing cries drifting away and a repetitive, processional hook that gets lodged in your back brain.

That hook shows up again and again when you listen for it. It's turned into la-la-la’s by male voices on "Beautiful Hair." It gets a brief, slow, lyrical treatment on "Confession Modulation." And then it's rolled out for a full–length song treatment on "Teresa, Lark of Ascension," the album's longest and most realized track. Trish Keenan, Broadcast's singer, has a light, unearthly voice, which lifts up and wraps around similarly unearthly bells while her multi-tracked mirrors wordlessly imitate the keyboards and the keyboards soar up to try to imitate her voice. Halfway through, the echoey washes of wind come through and the voices lose purchase, until you're just left with that same motif and a dramatic organ flourish. If she's ascending to heaven, it's an oddly self-referential, artificial hereafter—like she's a lark transubstantiating into an exact facsimile of a lark.

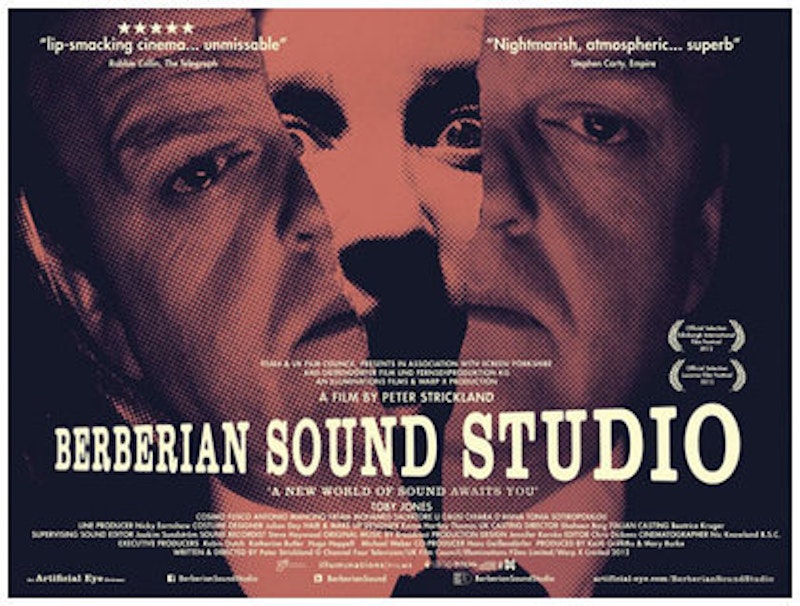

The sense that the soundtrack is deliberately erasing itself and spiraling into itself is perhaps thematic. As noted above, I haven't seen the film by Peter Strickland, but it's about a man going mad while making a horror film. The awesomely titled six-second track, "The Serpent's Semen," which is basically a single scream, is more than a little self-conscious. The scream means "scream" just as the atmospheric soundtrack means "atmospheric soundtrack"—and the ambient blankness, presumably, means "ambient blankness."

The sad twist to this is that Keenan was already gone by the time this album was released—she died of H1N1 flu in 2011. The soundtrack, with its self-referential devotional mode, then, ends up as a kind of unintentionally painful self-referential requiem. That beautiful voice fades into the background. If you're listening to this and thinking of a horror movie, it's one in which there aren't really any surprises or shocks. Instead there's just the wallpaper watching while something else happens somewhere, flat and blank and knowledgeable as grief.