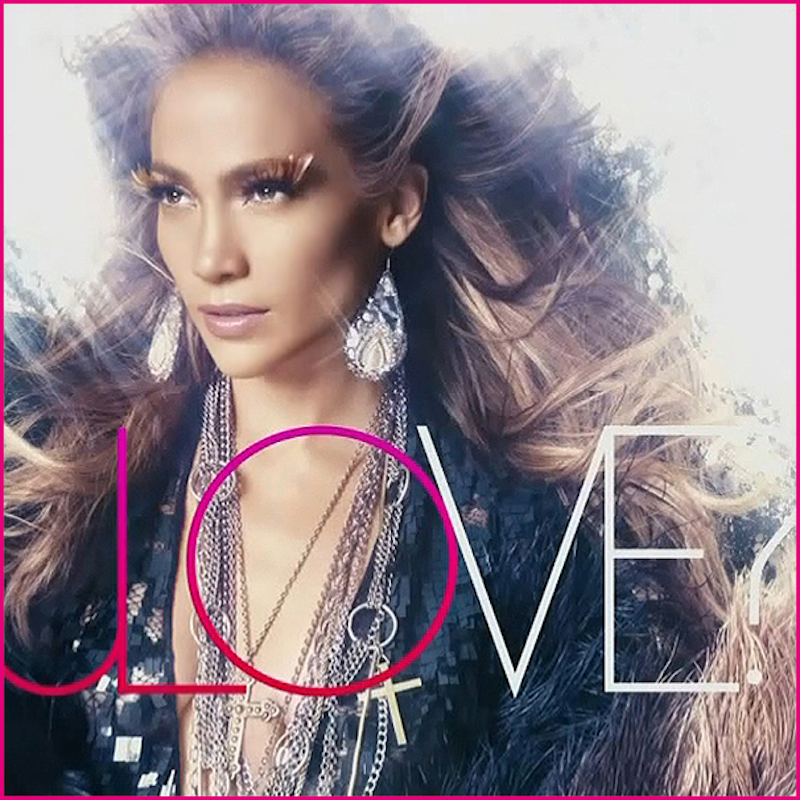

I downloaded Jennifer Lopez’s new album Love? on May 10, the day it was released. At the time, I was surprised to see that there was only one review on Amazon. A week or so later, there’s a bit more interest; the deluxe edition has 16 reviews and the regular edition has eight. Still, that seems like pretty small beer for a pop star. Indie darlings the Fleet Foxes, whose album came out the same day, have 32 reviews for Helplessness Blues.

J.Lo is more famous than the Fleet Foxes; Robin Pecknold’s butt has yet to become a tabloid sensation. But her greater exposure (as it were) doesn’t necessarily translate into greater interest in her album. In part, this is because her album simply isn’t that interesting. Love? is listenable dance floor fodder, and I’d even argue that the Danja-produced “Starting Over” attains a level of bittersweet confectionary genius. But even a rank popist such as myself can’t argue in good conscience that the album as a whole makes a coherent, or even incoherent, statement. The most you can say for Love? is that it’s a bunch of decent or good songs, some of which exist as vehicles for videos which will include images of Jennifer Lopez shaking it.

Still, the utter irrelevance of Love? is in itself a kind of relevance. Even Britney and Lady Gaga (who penned “Hypnotico,” a song Lopez turns into—wait for it—anonymous dance floor fodder) continue to work hard on album releases. For Lopez, though, the album seems like barely an afterthought. And, as Damian Kulash of OK Go noted in The Wall Street Journal, that makes her cutting edge.

Music is as old as humanity itself, and just as difficult to define. It's an ephemeral, temporal and subjective experience. For several decades, though, from about World War II until sometime in the last 10 years, the recording industry managed to successfully and profitably pin it down to a stable, if circular, definition: Music was recordings of music […] Then came the Internet, and in less than a decade, that system fell […] Music is getting harder to define again. It's becoming more of an experience and less of an object. Without records as clearly delineated receptacles of value, last century's rules—both industrial and creative—are out the window. For those who can find an audience or a paycheck outside the traditional system, this can mean blessed freedom from the music industry's gatekeepers.

J.Lo’s music is certainly “less of an object”—a single disc or album—and “more of an experience,” videos, pictures in fashion magazines, American Idol-judging, or just being her wonderful, hard-bodied self. If you’re looking for an “ephemeral, temporal, and subjective experience”—well, she’s it.

Of course, when Kulash said, “blessed freedom” I doubt he meant “blessed freedom to make utterly predictable dance pop.” When he said the new music landscape would allow artists to make an end run around “music industry gatekeepers,” he probably wasn’t exactly thinking about the alternative platform provided by American Idol. He might be surprised to discover that the loss of a “stable, circular definition” doesn’t necessarily mean that music will metastasize into uncontainable forms. It may, on the contrary, mean that pop music may become more like itself.

This isn’t actually all that surprising. People sometimes think of capitalism as a frozen hierarchy, reducing ineffable jouissance to cold, solid materialism. But the truth is rather more sinister. Capitalism doesn’t create objects and boundaries; it destroys them. As Marx wrote in The Communist Manifesto:

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relation of society […] Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois epoch from all earlier ones. All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned […]

The fact that albums are going the way of the eight-track is not a triumph over music-as-product. Rather, it’s just another part of the ongoing ineffable revolution that is capitalism. The music industry is not being destroyed; it is being perfected. As it dissolves, it purifies. Records solidified and reified music. They bounded it and contained it in a magic circle that drew a line between the product and art, body and spirit. As albums have become friable, that separation between product and art, or to put it more bluntly, between marketing and art, has disintegrated. Getting rid of the body doesn’t make the body more sublime; it just makes the spirit fungible. Musicians used to at least pretend they were selling albums. Now, increasingly, what they have to sell is themselves. The future is Love?