In a recent memoir, Graham Nash—first with the Hollies, and then Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young—remembers the first time he heard the Everly Brothers’ song “Bye Bye Love.” Nash was on his way to flirt with a girl at the British equivalent of a high school dance when someone put on the tune. It had the power to momentarily halt Nash in his tracks and cause him to forget his lusty pursuit.

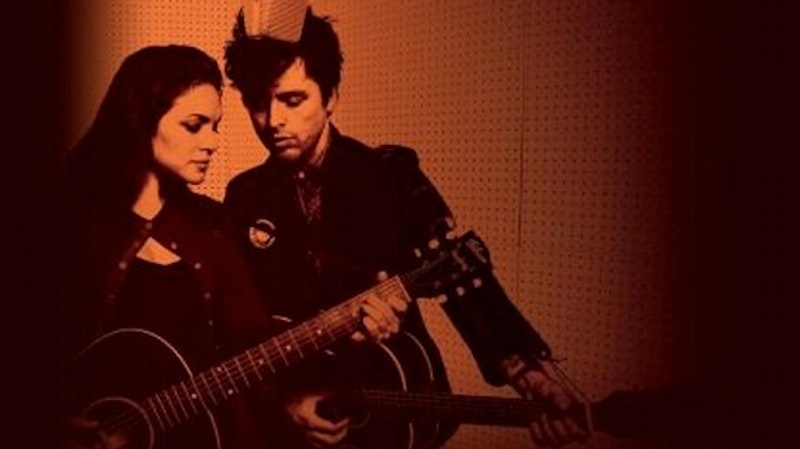

As the end of the year approaches, plenty will be written about musical trends in 2013, but most of these pieces won’t mention the sudden uptick in Everly Brothers tributes. Nash’s wasn’t the only one—back in February, the singers Bonnie “Prince” Billy and Dawn McCarthy released What The Brothers Sang, entirely dedicated to the catalogue of Don and Phil Everly. Providing some symmetry in the year, Foreverly, from Billie Joe Armstrong and Norah Jones, was just released. While the Bonnie “Prince” and McCarthy selected songs from across the Everlys’ career, Armstrong and Jones choose to re-do a single album: Songs Our Daddy Taught Us, from 1958, a record with an interesting history.

Songs Our Daddy Taught Us makes a virtue of concision, in length and instrumentation, and precision, in harmony. Guitars are the principal—usually the only—instruments; songs are performed with no flourishes and in tight arrangements. The Everlys’ voices don’t stalk or shadow each other so much as vie for the same space, breathe the same particles of air. The music’s almost claustrophobic, except for the cherubic innocence of tone. That innocence inspired singers in the 1960s, notably the The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel and the Byrds.

But don’t let the voices fool you: recording Songs Our Daddy Taught Us was a bold, maybe even stupid move, a partial rejection of the early rock and roll—the “Bye-Bye Love,” the “All I Have To Do Is Dream”—that brought the Everlys their burst of late 50s success. In a time when singles sold, they didn’t even release one from the album. At its quickest, Songs Our Daddy Taught Us moves at a lilting pace, but it rarely coheres around a firm rock backbeat; there’s no “Be Bop A-Lula” here. Instead, things tend towards the hymnal “Down In The Willow Garden,” or the waltzing “Lightning Express.”

The artists seemed pure and innocent, but this record was defiant, an early example of confounding expectations and turning their back on easy money and market demands. It’s possibly a decision they might have regretted later, because the Everly Bros. only enjoyed a short time in the limelight. The rock ‘n’ roll they helped inspire quickly moved past their idyllic charm, or took it in different directions. (Phil Everly didn’t have much to say about the album, telling The New York Times: “We did some strange albums in our time.”)

Where do Billie Joe Armstrong and Norah Jones fit in all this? Armstrong is known for his work as the lead singer of Green Day, which has a very distant relationship to the Everly Brothers. So diving into a more obscure selection from Don and Phil could be seen as a surprise. But one of pop’s standard career moves these days is for a veteran artist—the first Green Day album came out in 1990—to record some sort of tasteful, “rootsy” project, maybe working with old forms of Americana, covering some jazz standards, or doing a soul-lite album.

For Norah Jones, performing Everly tunes is less of a departure: her first album, which astutely combined soul, country, folk, and pop, existed in that tasteful, rootsy space already. She also covered one of the Everly’s predecessors, Hank Williams, on her debut. Her last few releases have moved into different sonic territory, but Jones has always been interested in older classics.

There’s one final wrinkle: Armstrong and Jones are not actually performing Everly Brothers’ songs, because Songs Our Daddy Taught Us mostly contains covers of traditional songs. So ArmJo are covering, song for song, an album of covers. They are channeling a lost innocence from a supposedly sweeter time—by paying homage to an album that was actually a bold release. There’s a lot of conflict at the foundation of the project.

On the surface, the result approximates the original. Armstrong and Jones work hard to evoke those close harmonies, though their voices are obviously more distinguishable. Interestingly, of the four Everly Brothers cover projects that come to mind, only one repeated the male-male singing that marks the original work: an EP released by Nick Lowe and Dave Edmunds in 1980. Bobbie Gentry and Glen Campbell sang Everly Bros tunes in the late-60s, as did Bonnie “Prince” Billy and Dawn McCarthy more recently; like Jones and Armstrong, these duets substituted male-female interplay for the signature male-male vocals.

This approach may not serve Jones and Armstrong well. Partially because of the different textures of their voices, it sounds less like a duet of equals, and more like Jones is serving as Armstrong’s backup singer. Usually they sing simultaneously; occasionally they trade off the lead vocal. There are times when Armstrong stops trying to sound sweet—though to his credit, he does a good job of escaping more than 20 years of built-in habit.

The other crucial change to the Everlys’ music is instrumental: the addition of a rhythm section, occasional flashes of electric guitar, and sprinkles of keyboards. The songs usually come on a little harder, a little quicker. Nothing charges forward, but everything is less wispy and delicate, the sound is fuller and thicker. The guitar is strong on “Roving Gambler,” the opening track; there’s an occasional kick drum, bursts of harmonica, a shuffling beat. “Silver Haired Daddy” is all rubbery bass and clicking drumsticks.

In Armstrong and Jones’ hands, “Down In The Willow Garden” leans towards the Animals’ “House Of The Rising Sun,” or an early Stax ballad. The guitar rises and falls in slow, inevitable waves, accompanied by military drum rolls, spurts of piano, weeping slide guitar. But the Everlys were trying to evoke “the way you’d sing those songs on your porch”—bare-bones and no frills.

The effect of these changes on Foreverly is predictable; it replaces the haunting fragility of Songs Our Daddy Taught Us with firmness and comfort. It’s tasteful, but it also relegates the past to a safe space for easy listening. The original album, quietly rebellious and sparsely unsettling, is wiped cleaned in this updating. This isn’t surprising, since Jones and Armstrong are engaged in archival work, resurrecting the past, dressing it up, and parading it in the present. It’s a conservative mission from the beginning—they even sang the vocals “live, making eye contact, as the Everlys had done.” But the strange thing is that they seem to be honoring a warped memory of a record, rather than the record itself.