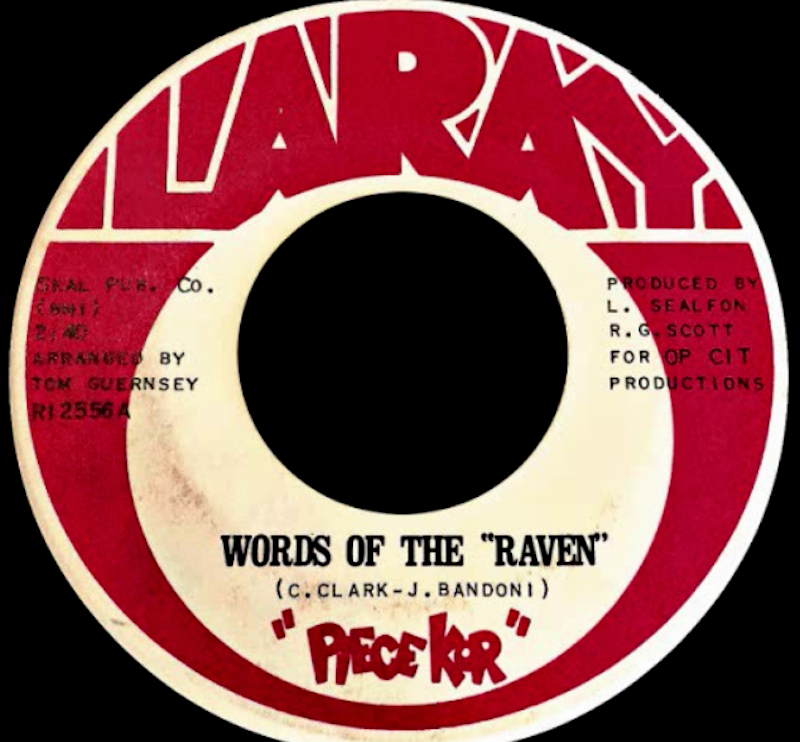

By the post-World War II era the fields and forests of northern Maryland’s Harford County began transforming into typical East Coast exurbia. Growth in the area was steady from the late-1800s through the 1930s. Between 1950 and 1970 Harford County’s population more than doubled, causing a dramatic dilution of the unique rural culture and natural beauty that existed there in pre-WWII years. To this day it’s a hodgepodge of suburban homogeny and bucolic remnants. 1960s teen rock bands that came from northern Maryland played music that reflected this clash of noise laden progress and organic energy. The greatest of these was a quintet called The Piece Kor.

The Kor’s story begins in Boston, birthplace of guitarist/songwriter Jack Bandoni. At age seven Bandoni began taking trumpet lessons and performing in school bands. Longing for a taste of shaggy-haired glory, the teenaged Bandoni traded in the trumpet for a guitar once The Beatles hit the US pop charts. In early-1965 his family moved to the Harford County town of Bel Air, MD. There Jack joined up with a modest bunch of rockers called The Zotos. They were significant for being the first band to feature collaborations from Bandoni and future Piece Kor vocalist Mick Ball. Richard Lynch was their bassist. Other members’ names have been forgotten.

It quickly became clear that The Zotos would never get out of the garage. Bandoni, Lynch, and Ball then left the group to form a new band who went by the name The Clan, one of several 60s rock hordes to brandish that loaded moniker. They had no hateful political agenda and merely chose the name because it sounded British. Any British cultural reference was cutting edge by the standards of 1965’s Beatle-crazed teen scene. Along with Bandoni, Lynch, and Ball, there were two other members whose last names are now forgotten—Alvin on drums, and Gary on organ. Their sets were dominated by early-1960s surf rock and British Invasion covers.

The Clan’s disastrous first show occurred at St. Margaret’s Church in Bel Air. That night Lynch got into an on-stage shouting match with his girlfriend. Lynch’s paramour objected to him playing in a band and gave him an ultimatum: quit The Clan or get dumped. Love won out in the end and Lynch ditched the gig before the group had even finished a song. Bandoni and the others soldiered on, but things remained shambolic. Early in the set the guitarist broke a string and didn’t have a replacement. The only song Jack could play without all six strings was The Surfaris’ “Wipeout.” They played the surf classic non-stop for 45 minutes, much to the chagrin of a dumbfounded audience.

Undeterred by public embarrassment, they stayed active gigging throughout the final months of 1965. It was then that Lynch’s younger sister started dating 14-year-old bassist Barry Scott. When she found out that her older brother had quit The Clan she secured an audition for Scott. Barry established a great rapport (musically and personally) with the rest of the group. Shortly before Barry’s audition, drummer Charlie Clark replaced the mysterious Alvin. The new drummer was 19, a few years older than the others. Clark had an impressive resume: he drummed for Bel Air’s The Malibus and Baltimore stars Tommy Vann & The Echoes. By this time the band were no longer called The Clan; they started going by a name that was still very Anglo-inspired: The Knights of Sound.

Knights gigs occurred at all of the standard teen hot spots—church halls, Knights of Columbus halls, armories and U.S.O. dances located in and around the region’s large military installations (Aberdeen Proving Grounds and Edgewood Arsenal), school dances, and teen centers. Gigging territory rarely extended too far from home, but they did occasionally rock out in northeast MD’s Cecil County. HarCo’s macho hippy haters and jarhead bullies seemed harmless compared to the menacing hillbilly element that confronted them in Rising Sun and Elkton.