I’ve just finished reading The Hard Stuff, Wayne Kramer’s 2018 autobiography. Kramer was the lead guitarist and co-founder of the Detroit band, The MC5. It’s a very affecting read, the story of an aspiring musician brought low by drink and drugs, and then brought back to life again by love and music. He spent time in prison, from 1975-1979, while the punk music scene he inspired was taking off in Britain and the United States.

There’s a great interview with him on YouTube with DJ Jim Kerr. He talks about his incarceration for what he describes, with a broad smile, as “illegitimate capitalism”: meaning he sold drugs. He talks about the American prison system. There’s no such thing as a country-club prison, he says. It’s always hard, always destructive on families. He describes the system as medieval, and talks about the warehousing of human beings and the failure to rehabilitate. You’re sent to prison as punishment, not for punishment, he says. He also talks about his initiative, Jail Guitar Doors (after a song by the Clash which mentions Kramer) which involves providing guitars and tutoring for prisoners so that they can engage their complex emotions in a creative way.

He talks about his book—“your mistakes are how you learn,” he says—and about his addictions. “Was there—somewhere in your young confused mind—was there the allure, the romanticism of the tortured addicted artist?” asks Kerr. “I read William Burroughs, and read about other criminals and lowlifes and hard-drinking authors, you know, Hemingway and Byron, and the whole history of drugs and creative people,” says Kramer. “None of that caused me to be an addict. What caused me to be an addict was, I liked the effect of those potions when I put them in my body.”

He adds: “Life brings some pain with it. The Buddhists say life is suffering. And at a time in my life—I was in my early 20s—we know now in your early 20s your brain isn’t even done growing, and my life had collapsed. My way to make a living, the MC5, everything I’d worked on since I was 13 years old, went away. The band broke up. And this is not unusual. Most bands break up. Most bands don’t have the FBI tapping their phones, dealing with the police department on a daily basis, but the MC5 did, and one day it all went away and I suffered incredible grief from that loss. I lost my best friends, I lost my brothers, I lost my community, and I was in more pain than I was even conscious of.”

He says he was suffering from something akin to PTSD. He’d been traumatized by the experience and he discovered that these substances, alcohol and opiates, killed pain. He was self-medicating for his trauma, he says.

The MC5 weren’t just a band, they were an attitude. They were at the cutting edge of a political movement, the revolutionary, acid-tinged youth movement of the late-1960s and early-70s. That’s why the FBI were tapping their phones. They were members of the White Panther Party, set up in 1968 by John Sinclair, who was also their manager. This was in response to Huey P. Newton of the Black Panther Party, who was asked what white people could do to support them. Newton replied that they could form a White Panther Party, which is what they did.

Those who espouse revolution are often destroyed by it. The MC5 were just too in-your-face to last. They had an early hit with Kick Out The Jams, probably still their most famous song. As a single it opened with their lead singer, Rob Tyner shouting the words, “Kick out the jams brothers and sisters!” On the LP the introduction is more aggressive. “Kick out the jams, motherfuckers,” he roars. This led to a ban from Hudson’s, a Detroit based department store. The MC5 responded with a full page advertisement in the local underground magazine saying, "Stick Alive with the MC5, and Fuck Hudson's!" It included the logo of their label, Elektra Records. Hudson's pulled all Elektra records from their stores, and as a consequence, Elektra dropped the band. They later signed with Atlantic.

The origin of the phrase “kick out the jams” is interesting. People think that it’s an anarchist slogan, meaning to kick over all barriers, but Kramer tells a different story: “People said oh wow, kick out the jams means break down restrictions etc., and it made good copy, but when we wrote it we didn't have that in mind. We first used the phrase when we were the house band at a ballroom in Detroit, and we played there every week with another band from the area. We got in the habit, being the sort of punks we are, of screaming at them to get off the stage, to kick out the jams, meaning stop jamming. We were saying it all the time and it became a sort of esoteric phrase.”

There’s also another, alternative interpretation. This is from Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea's epic satirical novel Illuminatus! In this version the evil Illuminati, who rule the music industry (as well as everything else) use it as an attack upon their good-guy rivals, the Justified Ancients of Mummu (JAMs for short). “Kick out the JAMS,” therefore means kick out the Justified Ancients of Mummu. This makes the MC5 agents of the Illuminati and their hit single a rallying cry for the counter-revolution!

Obviously this is a joke. The opposite was the case, and it was their identification with the 1960s revolutionary movement that was their undoing. John Sinclair was arrested on a drugs charge, and the band soon found themselves at the sharp end of his bitter prose. “They wanted to be bigger than the Beatles, but I wanted them to be bigger than Chairman Mao,” he said. They were more interested in fame and wealth than they were in revolution, he said. Kramer denied this. They weren’t even allowed to take part in the benefit to raise funds for Sinclair’s defense. It was a case of the revolution eating itself, as former comrades turned on each other, a not uncommon occurrence when stress, political pressure and government interference get in the way.

There’s been a lot of debate over the years about who the first genuine punk band might have been, with fellow Detroit band the Stooges often coming high on the list. The MC5 are also contenders. They were older, more accomplished, and had been going for longer. In the early days of the scene the Stooges were like the MC5’s younger brothers, and it was the MC5 who got the Stooges their first recording contract, when both bands were signed to Elektra in 1968. The Stooges were never burdened with any political baggage, however. They just got on with perfecting their stage act and becoming the model on which the punk rock revolution was based.

It’s true that there are certain parallels between the sound of punk and what the MC5 were trying to do, but this can be overplayed. The MC5 were loud, energetic, fast-paced, working class and overtly political, but Kramer was/is an accomplished musician, and capable of playing extended guitar solos, something that was an anathema to the punk bands, mainly because they were much less musically gifted. The MC5 were into Free Jazz and Hendrix. Unlike the punk bands they were celebrating virtuosity and attempting to achieve it on their own terms.

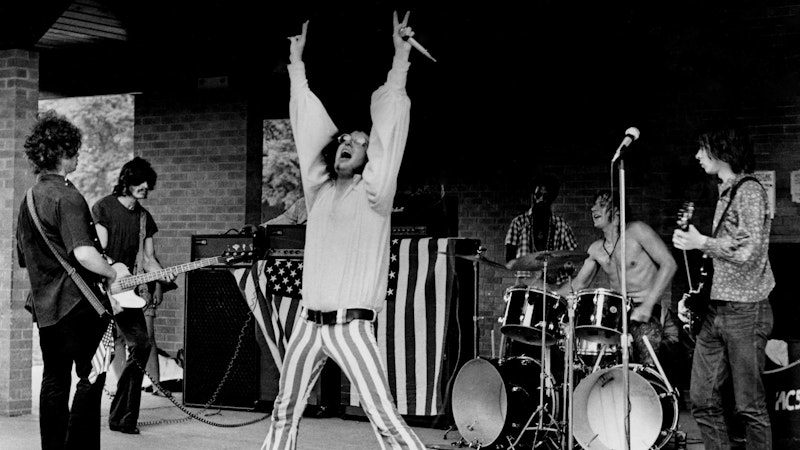

Other bands refused to follow them on stage. They were electrifying and dynamic, with the audience often calling for numerous encores. They used to blow other bands away with the sheer energy of their performance, including name bands like Cream and Big Brother and the Holding Company who refused to share a stage with them. They made the front cover of Rolling Stone even before their first LP was out. They also spent time in the UK and famously headlined Britain's first free festival, Phun City, held on Ecclestone Common, Worthing, in July 1970.

I’ve written about the origins of the word “punk” before. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary it means "something worthless," from "rotten wood used as tinder", possibly from the Algonquian language, ponk, meaning "dust, powder, ashes." Later it came to mean a worthless person, often associated with criminality, as in “punk kid” meaning a criminal’s apprentice. However there’s an earlier use of the word. It appears in The Fairy Queen by Henry Purcell (1692), Act I, Scene 1, and refers to the lead character’s Fairy tormentors, who are pinching him repeatedly, asking him to confess his crimes:

DRUNKEN POET: Hold you damn'd tormenting Punk, I do confess...

It’s used in Shakespeare too, in Measure for Measure (1604), Act V, Scene 1:

LUCIO: My lord, she may be a punk; for many of them are neither maid, widow, nor wife.

The suggestion here is that she’s a prostitute. According to the Oxford English Dictionary the first recorded use of the word is in a ballad called Simon The Old Kinge, dating from before 1575. It warns men that drinking is a sin akin to keeping prostitutes: “So fellows, if you be drunk, of frailty it is a sin, as it is to keep a punk.”

By the late-17th century it had acquired the meaning of a male prostitute, a boy or younger man kept for sex by an older man, which is also how it was used in US prison slang. A punk was a weaker prisoner forced into sex by a dominant prisoner. Later it was used to describe any contemptible or worthless person, a petty criminal, a coward, a weakling, an amateur, an apprentice or an inexperienced youth.

It was first used as a musical term in 1971 by journalist Dave Marsh to describe 1960s garage band, Question Mark and the Mysterians; also by Suicide, an electronic duo from New York who, in an advertisement in 1970 described their performances as “Punk Music.” Suicide gigs often ended in violence. The Ramones used it on their debut album in 1976, on the track Judy Is a Punk. It was after this that it was adopted by bands, both in Britain and the United States, to describe their brand of raw, aggressive, back-to-basics rock ’n’ roll.

There’s a long history of former insults being turned into accolades, as in the word “wicked,” which originally meant evil but came to mean good, or the word “funk,” which first meant a bad smell, but later meant a groove. The word “geek” was originally applied to a circus act. A geek was someone who bit off the heads of live chickens or snakes for entertainment. So it was with punk. The word was applied to lowlifes and criminals, but was adopted by young music and fashion aficionados as a badge of honor, much as the word “freak” had been adopted by the hippies earlier.

Kramer was less keen on the word at first, it having negative connotations in the culture he was brought up in, but in the end he learned to embrace it. “I appreciate punk rock, and I get the aesthetic completely,” he says. “It’s been said that I invented it. I remained a punk philosophically but I wasn’t about to become a punk in the latest cultural iteration. I hadn’t been that since I was 20 years old.”

Kramer’s book is gloriously honest. He wasn’t only a drug dealer and an addict, he was a thief. He was a punk in one of the original senses of the word, a young criminal. He tells the story of his life with such disarming candor it’s hard not to love him. After the break-up of the band he did all sorts of work to earn a living. He was a carpenter for many years. It’s this connection with ordinary life that gives Kramer his particular voice.

The book is beautifully written, without the aid of a ghost writer. It’s simple, clear and concise, observing the mistakes of his past with empathy and insight. He’s like everyone’s older brother, someone who has lived a life and suffered, but who has returned home from the wars chastened but wise, with a deeper understanding of what life is all about. His is the voice of wisdom. We’d be fools to ignore it.