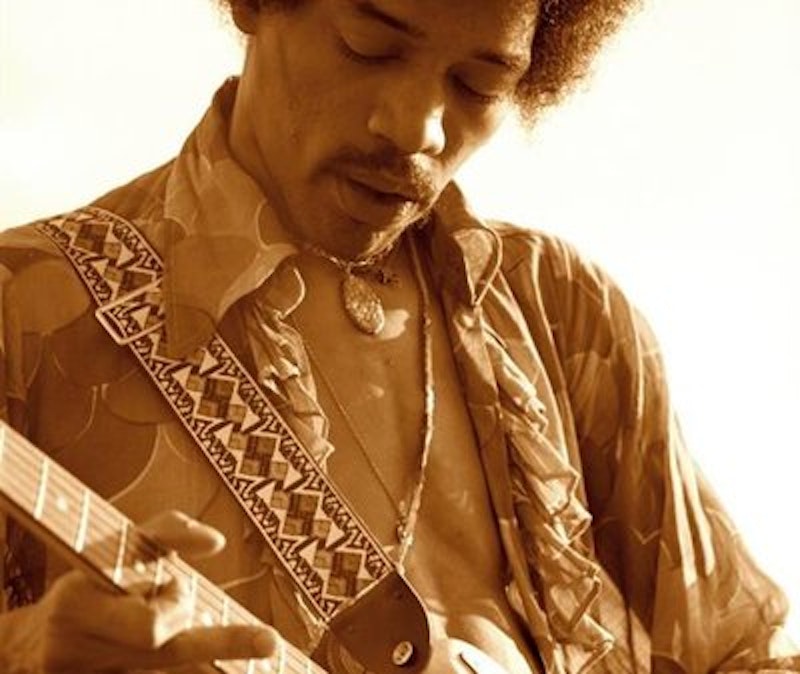

There’s not much left to say about Jimi Hendrix. Few figures in the history of pop music (Hendrix didn’t like the word “pop“; to him, it meant “Pilgrimage of Peace”) have been picked apart more thoroughly, aside from Bob Dylan or John Lennon. But Hendrix books keep appearing, as does the music—another posthumous collection, People, Hell And Angels, came out in March of this year—and a biopic is showing up in the States at some point, with the rap star Andre 3000 portraying the famed guitarist.

The latest book, Jimi Hendrix: Starting At Zero, stakes its contribution on methodology: it’s composed entirely of the artist’s words, assembled from a variety of places, including “interviews, concerts, recorded conversations and… [Hendrix’s] writings and poems.” (A crew of three put the book together: Alan Douglas, who worked with Hendrix, Peter Neal, who made a short film about the guitarist in the 1960s, and Michael Fairchild, described as a “superfan.”) The book’s website works to dispel any fear that the text is interpolated or fabricated. No quotes are taken from other books on Hendrix in which “associate[s]… reconstruct” conversations “from memory.”

Almost every “print-source quote” in Starting At Zero “was published during Jimi’s lifetime.” Some of text comes from Hendrix’s “handwritten poems, lyrics, notes, and stream-of-consciousness explorations” which went up for auction at Sotheby’s in 1990 and 1991. In addition, roughly 40 tapes (audio and video) of conversations with Hendrix factor into this creation.

Still, “[a] single paragraph might be composed from a half dozen different sources,” so it is hard to know how cobbling together the quotes impacts the narrative. The authors note that, “[a] traditional ‘footnotes’ listing would look extreme in length,” and be unwieldy enough to “compete with the book text itself.” The reader has Hendrix’s words, and presumes they aren’t stitched together like a movie ransom note, cut out from unrelated pieces of magazines. The book likes to play with the font, text color, and form, making IMPORTANT words POP OUT of paragraphs in bold color for extra emphasis, meaning that the text sometimes resembles a strangely collaged ransom note.

One of the benefits of using the artist’s actual words: there are a limited number of them, so no author gets to milk Hendrix’s first 20 years for extra hundreds of pages. (The book adds padding by including numerous transcriptions of song lyrics.) The twists and turns of early life are sketched quickly but not dwelled on. Born in Seattle, Hendrix dropped out of high school and ended up joining the paratroopers. On one of his early training jumps, he miscalculated and “ran smack dab into a sand dune.” “Oh well,” he writes to his family, “it was a new experience.”

After leaving the army, Hendrix worked in countless bands, touring every corner of the country with pretty much any early R&B singer, blues singer, and rocker you care to name, and probably a lot that you wouldn’t. The list includes the Isley Brothers, Sam Cooke, Solomon Burke, Jackie Wilson, Hank Ballard, B.B. King, Wilson Pickett, Little Richard. Hendrix quit a lot of groups—Little Richard told him, “I’m the only one who’s going to look pretty on stage,” cramping his young guitarist’s fashion sense—and spent plenty of time sleeping in alleys. Chas Chandler, bassist for the Animals, saw Hendrix play in Greenwich Village and convinced him to come to England, where they recruited the other two members of the Experience and exploded into the big-time.

The most valuable thing about the “Hendrix’s words only” approach is that through collecting and distilling various non-musical expressions of his thoughts and feelings, it allows Hendrix to take a crack at his own story—a story that has moved so far into the realm of rock myth it’s hardly connected to a person anymore. Everyone knows he’s a prodigiously talented guitarist who died too young. The radio reduces his catalogue to a handful of straightforward tracks. The myth is defined by a few big, easy tropes.

The man is obviously less skeletal, so it’s interesting to hear Hendrix outlining his aesthetic principles. He appreciated English recording studios, because of their inferior technology. “In England, the studios don’t have anything to work with compared with what they have here in America. Then they come out with the best sounding records and the most new sounds. Even the limitations are beautiful… the engineers have more imagination over there.” Hendrix saw a kindred spirit in some of these engineers, who worked creatively with the basics to move sonics in new directions. (Though he eventually built an American studio for himself, supposedly the first one to be owned and operated by an artist.) “We never do more than five or six takes in a record studio… too expensive,” he complains, but he later spent $60,000 dollars trying to do justice to Electric Ladyland. (Building his studio cost him quite a bit too; the place is still in use today.)

Some of Hendrix’s insights about other artists aren’t entirely accurate, but they’re still amusing. “The Beatles and the Stones are all such beautiful cats off record, but it’s a family thing, such a family thing, that sometimes it all begins to sound alike.” This depends on your definition of “beautiful cat” and “sound[ing] alike,” but it’s endearing in its cheery dismissiveness. Also: “I would under no circumstances call my music psychedelic,” he says. “You hear these cats saying, ‘Look at the band, they’re playing psychedelic music,’ and all they’re really doing is flashing lights on them and playing ‘Johnny B. Goode’ with the wrong chords.”

This sounds like a critical judgment, which is funny, because Hendrix isn’t a fan of the critics. “Critics really give me a pain in the neck. It’s like shooting at a flying saucer as it tries to land, without giving the occupants a chance to identify themselves!” When someone plays Hendrix a series of songs and asks him to identify what’s playing and talk about it, he has this to say about the Beatles’ “She’s Leaving Home:” “Who’s that? It’s not the Beatles, it’s too commercial… Everybody is so worried about the Beatles and where they are going. It’s so silly. Just take the music for what it’s worth. I wish we could end up like them!” His general jolliness overwhelms his occasionally self-contradictory impulses.

As everyone knows, though, Hendrix’s story isn’t a comedy. And that’s the thing: everyone knows. His tale is ubiquitous. The methodological approach to his life is inventive—a recently-released book of John Lennon’s letters attempts the same thing, recasting Lennon in his own words. But Hendrix long ago reached the point where each subsequent volume on his life battled the law of diminishing returns.