Experimental music is supposed to be challenging. If you're a fan of the genre, you expect to hear piercing blasts of static, tortured electronic squeaks, or long passages of ambient drift in which nothing in particular happens. It's often irritating, boring or both; part of the fun is enduring it.

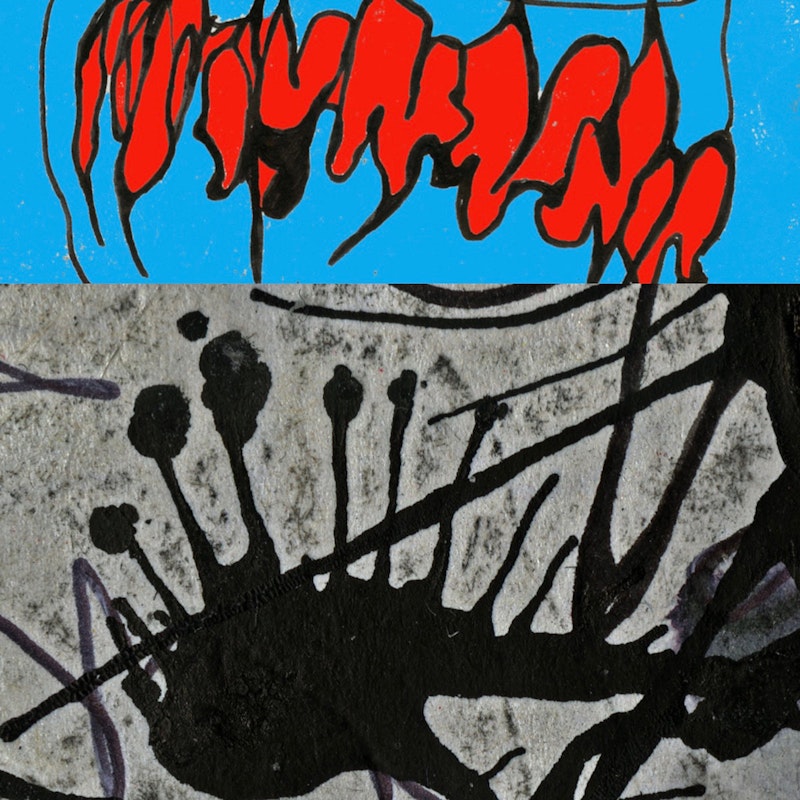

Gwilly Edmondez's new release is, by those standards, exemplary experimental music, for it’s hard to imagine anything could be more irritating or boring than Trouble Number (Slip). Culled from decades of recordings going back to the 1980s, the album is 90 minutes of formless moaning, muttering, and whining accompanied by random strumming and beeping. Imagine an extremely drunk Tom Waits imitator setting up at open mic night in the back room of a recreation center and improvising spoken word poetry for five minutes… then 10 minutes… then an hour. And he's still going on, so that time dilates and listeners actually begin to throw themselves from the windows, only to realize they're on the first floor and that there’s no escape. So they come back inside and he's still going.

God help us.

Edmondez has a slightly less obscure project called Yeah You, a band with his daughter that is almost recognizably punk. She screams and yaps, he provides abrasive beats.

With just himself and a recording device, though, Edmondez's work becomes, impossibly, more formless and self-indulgent. "Extinct Lord" sounds like the Shaggs trying to do gothic metal. "You grow inside me like a shadow of light/that illuminates the wrongs" Edmondez grunts in a slowed-down guttural burble, using effects to turn his voice into squeaking feedback yowl. He scats randomly before everything winds down and he finally observes, "Oh that makes a lot more sense now," even though, obviously, it doesn't.

On "Bent Oath Scenario," Edmondez lines out rumbling vocal lines like he's doing some sort of concussed plainchant, then starts swatting at his guitar, which emits a bunch of twangs and spits. There're splashes of cowboy yodeling and occasional falsetto. "Cry cry cry cry." Okay.

The first half hour of shorter songs is plenty unendurable, but Edmondez is absolutely fearless in trying your patience. The final two-thirds of the album is just two tracks of exactly 30 minutes each, "INTROSPEX" and "OTROSPEX." Both "songs" meander and spit and squat by the side of the road to do their business before getting up and slogging ahead. Bits of sub-beat poetry prattle and rise up like stale farts. "You've got an all seeing eye. And that's one thing that everybody is jealous about. You can see everything." Sped up chipmunk voices twitter inaudibly, melodies try to surface and are viciously stepped on; dance floor New Wave beats almost get under way and then give up. "We thank thee lord, apparently," he declares against fragmented organ blurts at the conclusion. "Lord we say these things unto you so that you may hear that we say these things to you." The nonsense is nonsense is nonsense. What are you going to do about it?

By the time Edmondez finally stops twiddling with knobs, I was ready to throttle him. The album is infuriatingly self-satisfied. He has deliberately, egregiously wasted your time for hours, and just sits there grinning. You're supposed to admire the genius of incapacity, and thank him for rambling on in sodden quasi-profundity without purpose or genius for eternity, or close to it.

Trouble Number isn’t enjoyable. But Edmondez wanted to create an off-putting, infuriating mess, and he succeeded. It's not that the music is so bad that it's good. It's that it's so bad that aesthetic judgment feels inadequate to the task of expressing revulsion. I can't recommend buying it. But listening to it is a unique and impressive ordeal.