Nick Cave is not necessarily known for restraint. On the contrary, his career has mostly been devoted to ravenous gothic excess; to teetering, gibbering show tunes about murder and hell and despair.

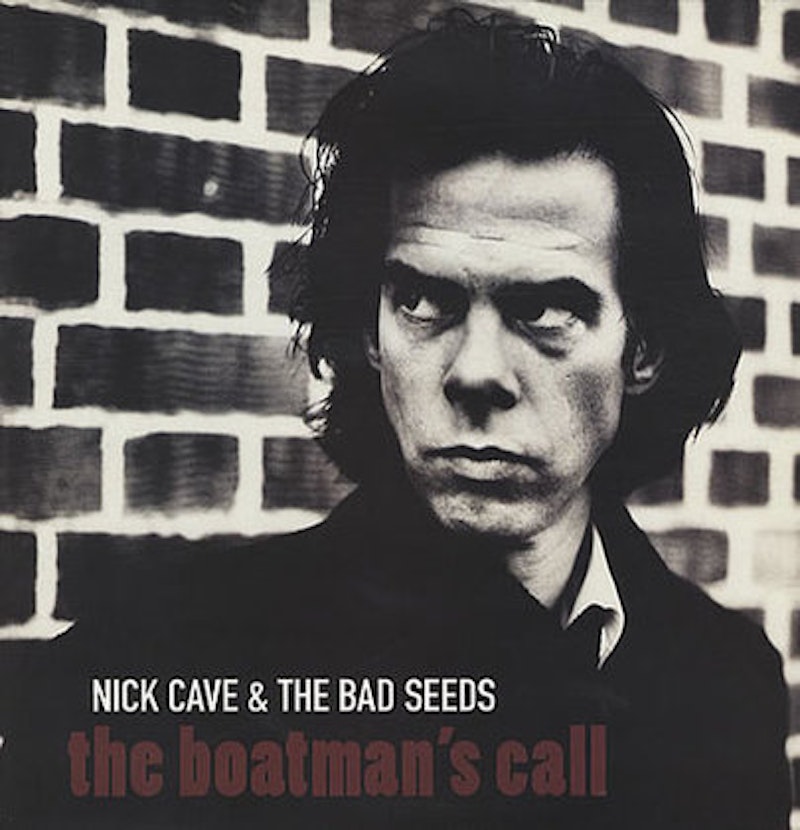

Which is why it's so odd that his best album is also his quietest. The Boatman's Call, from 1997, is filled with slow, gentle, piano-based tunes. Most of the lyrics are about love—often requited love. "Lime-Tree Arbor," for example, couldn't be much more inoffensive.

The boatman calls from the lake

A lone loon dives upon the water

I put my hand over hers

Down in the lime-tree arbor

That's the first verse. If you're a Nick Cave fan, you're probably expecting him to murder her and dump her in the water by the end of the song, or to reveal that she's a corpse, or something grisly and gruesome. But nope; the lyrical music ripples on as gently as the loon diving down, and Cave's baritone never wavers in its sincerity. The only thing that happens is that he touches her hand and she touches his. That's the song.

And yet, somehow, even while sketching an idyll, the gothic excess hovers overhead. In "Lime-Tree Arbor," the music's measured tread, the minor colorings, and Cave's mannered delivery all gesture towards a darker outcome, or at least a darker possibility. "There will always be suffering/It flows through life like water," Cave declaims, and it flows through the song too, so that the touch of two hands seems like it occurs above, or next to, an abyss. Cave's trademark hyperbole hasn't deserted him; it's just moved to the background, so that he’s not so much proclaiming love as clinging to it against a wailing blackness.

This is perhaps even clearer in the album's best song, "Into My Arms." Built around a simple, semi-classical repeating piano figure, Cave opens by stating with full-on, slow-burning romanticism:

I don't believe in an interventionist God

But I know darling that you do

But if I did I would kneel down and ask him

Not to intervene when it came to you.

By proclaiming his disbelief in God, Cave paradoxically opens his love song up to the divine. When he declares, "But I believe in love," it becomes, not a standard pop song trope, but a desperate substitution for religion, which is all the more moving, and all the more sexy, because of its desperation. As in Matthew Arnold's "Dover Beach," atheism becomes all the more reason to "love one another.”

The Boatman's Call, then, doesn't so much break with Cave's past style as it re-channels it. Instead of laughing maniacally with the gargoyles on the rain-swept church front, for this album Cave puts us inside the church, huddled together on a pew, listening for the storm outside we can't quite hear.

The album's smallness is, in its own way, every bit as histrionic as Cave's slavering murder ballads. The theatrically, ironically self-deprecating moroseness which only becomes more sincere because of its own self-conscious artificiality is reminiscent of the Smiths. Though I don't think even Morrissey has ever managed a song as preposterously bleak and bleakly preposterous as "Where Do We Go Now But Nowhere?"

In a colonial hotel we fucked up the sun

And then we fucked it down again

Well the sun comes up and the sun goes down

Going 'round and around to nowhere.

Ennui becomes as portentous as a gallows dance, and the dance becomes little more than ennui. "The carnival drums all mad in the air/Grim reapers and skeletons and a missionary bell/O where do we go now but nowhere?" is sung at a funereal pace.

The song may be about losing a child, or simply about losing a relationship, but either way, mundane grief bloats and staggers, emotions becoming hypertrophied parodies and then helplessly collapsing. Excess exhausted and exhaustion as excess roll over each other and whelm and wane, till you can' t tell if you hear a Brobdingnagian bellow from a long way away, or a muted call from your decadent heart.