In the fall of 1998 I was lost in New York City, a small-town Michigan boy, some years out of college, where I'd given up music for writing and meanwhile ended up on a wild adventure as a seasonal wildland firefighter for the Forest Service in Arizona. I was in an MFA at The New School for Social Research, which I'd picked only because Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac had taken classes there, half a century before. I just wanted to learn more about writing, and instead found myself in a big scary ugly city renting an awful noisy room in an expensive apartment, and in a class full of Language poets. And going into debt.

I was a metalhead, or had been. And a musician, or had been. I quit after being in a band with both a homophobe and a racist. Instead of re-inventing myself musically I made the decision that I didn't want to be a band anymore, didn't want to be dependent on other people, and so writing—my bad metal lyrics about witches seemed a good lead-in to poetry and novels. But I also told myself, or needed, to stop listening to metal, to not associate myself with “that crowd.” But besides a brief fling with Edie Brickell and The New Bohemians, I hadn't found anything that appealed to me, musically.

What I missed was a certain darkness—metal wasn't about hatred though it could be angry, and it definitely always came in a minor key. (My metal roots had led me to some interesting paths—I'd “discovered” the poet Sharon Olds simply because one of her books was called Satan Says—how metal was that?) The world was a sad and confusing place (I still believe this) and I liked music that reflected that. I liked Edie Brickell, I’d liked The Beatles my whole life, but anything not metal was happy and pop-y and ugh, I couldn’t take that all the time, then everything starts to sound a lot like Christmas.

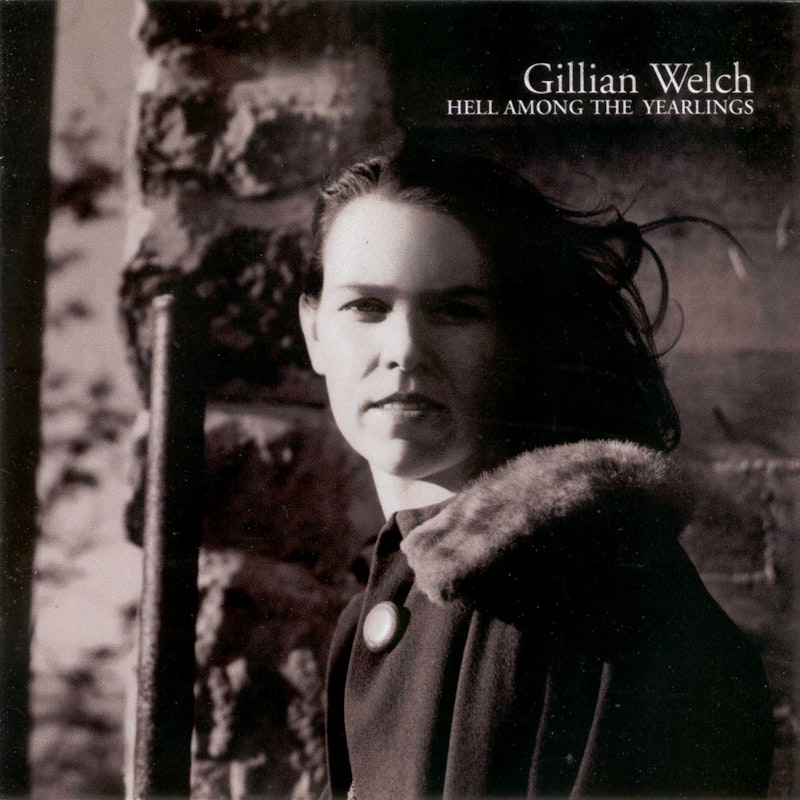

This was back when we still had record stores, or music stores that sold CDs, and in particular the Virgin Megastore, where at one of the listening stations I found a Gillian Welch CD called Hell Among The Yearlings. That sounded metal. The cover featured a young woman who looked sort of fairy-folk-ish. Impish, with woods behind her. I put on the headphones, hit play, and what came out was odd, different—just two guitars, one playing rhythm in D major, while the second guitar plays a melody in D minor over it: dissonance. And dissonance was metal, or at least dark. And while the chord progression starts in D major, it drops to C major, then down to G— though common enough, not quite a major progression either. In fact, used in metal a lot.

The song "Caleb Meyer" tells the story of a woman in Appalachia whose husband leaves her for business in town. Another man, Caleb Meyer, appears, stating:

Where's your husband, Billie King

Where's your darling gone

Did he go on down the mountain side

And leave you all alone

Then the chorus comes in, with Billie King telling the ghost of Caleb Meyer

Caleb Meyer, your ghost is gonna wear them rattling chains

but when I go sleeping now, don't you call my name.

So we know Billie King is going to be haunted by this man, in a good way? As in desire? Is there a seduction going on here? Or in a bad way? Well:

...Caleb threw that bottle down

And grabbed me by my hair

He threw me in a needle bed

Across my dress he lay

And he pinned my arms above my head

And I began to pray

This is darker than any metal songs, which tend to avoid real life interactions. Billie King fights him and kills him by dragging a broken bottle across his neck. And still in the repeated outro chorus, Caleb Meyer haunts her.

This was dark! And acoustic! Sold. And I hadn't even gotten to "The Devil Had A Hold of Me"! Or "Whisky Girl," about a couple who experiment with “heroin weekends” "in the underworld"!

Gillian Welch's first two albums, Hell Among The Yearlings and Revival kind of kept me sane in jagged New York City, and they were my real introduction to Americana music—most of the songs on the two albums are just her and partner David Rawlings playing acoustic guitars and singing, though some, a few, bring in drums and bass and electric guitar. I stayed through the MFA program, increasing my debt, exploring all the bookstores, attending all the readings I could, and ending up like Susan Sontag, seeing a movie (a good one) almost every day. I did become a writer, in my mind somehow, from all that, at least in contrast to most of my classmates, if only, to paraphrase Charles Bukowski, "It's not that I was so good, it's that that they were so bad."

I ended up back west, where I belong, in Santa Fe, trying to make money as a writer and working at the Cowgirl restaurant and bar. And I had an acoustic guitar too—wanting to play music again. It felt good for my soul. I also learned to sing, with a goal to eventually know enough songs to busk (which I did years later) and some of the first songs I learned were Gillian Welch's, off those first two albums. Like I did when I was younger, playing along to whole Iron Maiden albums on my bass, I'd put on a Welch album play and sing along to the whole thing. I went on to singer-songwriters who didn't sound happy, from Johnny Cash, to Jerry Jeff Walker and most especially Townes Van Zandt.

Gillian Welch grew up in northern California, as she says in her song "Wrecking Ball," "just a little Deadhead," but went to college at the Berklee College of Music, in the songwriting program. She met Rawlings there, and they moved to Nashville. Though her albums are by "Gillian Welch," they’re a team: It’s not clear how much Rawlings contributes to the lyrics, but he plays guitar solos and overdubs, and records and produces the albums. Without him, there would be no Gillian Welch. Their last album, All The Good Times Are Past And Gone (2020) features both their names, with Rawlings sharing some of the lead vocals.

I never saw them perform, but bought every album. Their third, Time: The Revelator, is great, though I've not been as into their later stuff, from Soul Journey on, in the same way I like less of Sharon Olds' books after The Gold Cell. Likewise with Welch, but I still love the first three albums. Still, now that she and Rawlings have recently, in 2020, put out, in addition to All The Good Times, three more albums worth of "lost songs," which the Gillian Welch website says are all from the post-Time: The Revelator time period, before Soul Journey. With a nod to Welch's hero, Bob Dylan, and his (ongoing) Bootleg series, they're called theirs Boots. The earlier Boots No. 1, from 2016, contains mostly alternate takes of earlier songs (which are still interesting—and that version of "Paper Wings," with drums, is maybe better than official acoustic version).

Twenty years after being lost in New York City, maybe the Boots albums evoke some nostalgia for that time. Maybe I still feel lost, even though I've just re-entered the middle-class with a fulltime teaching job. I've just always returned to Welch—most recently when I was a fire lookout.

It's not that her songs are hard—you can play along to them after one or two times straight through. Nor are her melodies complicated—she's not an opera diva—which is easy to sing along to, which has always been the appeal of Americana or country or the blues. Someone wrote that Welch's songs sound like old standards, and I've been embarrassed to find out that she has recorded some standards (like "Make Me A Pallet On Your Floor," off of Soul Journey).

Almost all her songs are narrative-based: a story is told, usually by a fictitious (male) narrator, about falling in love with a woman, though many times there are no overt gender/sex clues, which I think is part of the appeal, and though she does have songs which are, or sound, autobiographical—like "Wrecking Ball," one of my faves, and one with rare drums and bass.

All of Welch’s songs are, above all, about the poor and working class, what country music used to really be, and what “Americana” was a return to: for that reason, you won't hear Welch played on any country music radio stations, in the same way you won't hear John Prine or Johnny Cash or even Emmylou Harris.

I'm aware, now, of the irony of discovering Gillian Welch in a Virgin Megastore in Manhattan, and that record companies and distributors were pushing her. Still, it's the power of music, that I was lost in that megalopolis and a couple of folks with guitars made me feel not so alone, and gave me permission—invited me—to come back to (dark and lonely and minor key) music for the simple love of it.