Canadian four-piece Eric’s Trip was one of the greatest 1990s rock bands. The eccentric group’s giant doomy riffs and sweet melodic hooks were entwined carefully and then dragged through a muck of homespun recording. That same lo-fi production turned their mellow acoustic ballads into brittle serenades. They performed with an overwhelming urgency; they seemed to make music while staring into oblivion. Vocalists Julie Doiron and Rick White sang forlorn lyrics in the hushed tones of a deathbed confession. This gorgeous sonic drama went on to become an element in projects that formed in the wake of the band’s break-up. More recent releases from Eric’s Trip alumni Doiron, White, Chris Thompson, and Mark Gaudet are enduring examples of raw pop-as-psycho therapy yet few know about this crew’s striking experimental film work.

White was the main songwriter in Eric’s Trip and he also designed the band’s album covers, creating an inimitable visual counterpart for their music. Dadaistic collage techniques were applied to blurry photo images and shadowy color schemes that recalled post-impressionism. The obtuse music videos created for their songs bore the signature of this unique blend with clunky old instant cameras traded in for clunky old motion picture cameras.

The music video for "Girlfriend" (from 1994’s Forever Again album) is the penultimate Eric’s Trip film. Shot in black and white somewhere in the Canadian wilderness, this exercise in bleak naiveté was co-created by White and Peter Holt. Throughout the film the band members are shown appearing and disappearing at the bottom of the screen, shot from the waist up, staring blankly. These moments are intercut with scenes of a small car that rolls along and eventually parks by the side of a country road leading into a forest. A girl (played by Tara Landry) begins wandering around in the woods. Sometimes she’s alone and other times she’s with a tall man in a wacky skull mask (Ron Bates) who’s lurching around a la Quasimodo.

The minimal action, the song, and its lyrics match each other with unflinching vagueness. It’s a sad tune with an acoustic guitar, but it’s not a ballad. It’s got a catchy hook, but also spectral back-up vocals and distortion sounds. The remote location, the strange but subtle costume, the sudden appearance and disappearance of the band—this forms a mystery of unresolved tension. The equally beautiful/ambiguous music videos they made for “My Room,” “Stove,” and “Sun’s Comin’ Up” explore similar themes.

Bits of their own style and rock ’n’ roll theatrics come together in the video for “View Master,” another Forever Again track. With an unforgettable riff, muscular prog rock rhythms, and some of the sunniest vocal harmonies ever crooned by White and Doiron, its easy to see why this is the band’s most famous song. Laura Borealis and Rick White co-directed this one and Rudi Blahachek gave it pristine cinematography, the one element that sets it apart from the band’s other visual work. Most scenes feature a stark motif that finds the group pantomiming the song in various outdoor locales and sharing space with a quarter- or half-section of blank screen. Different levels of light cut in and out as each sequence slides dramatically into the next going from full color sheens to black and white moodiness.

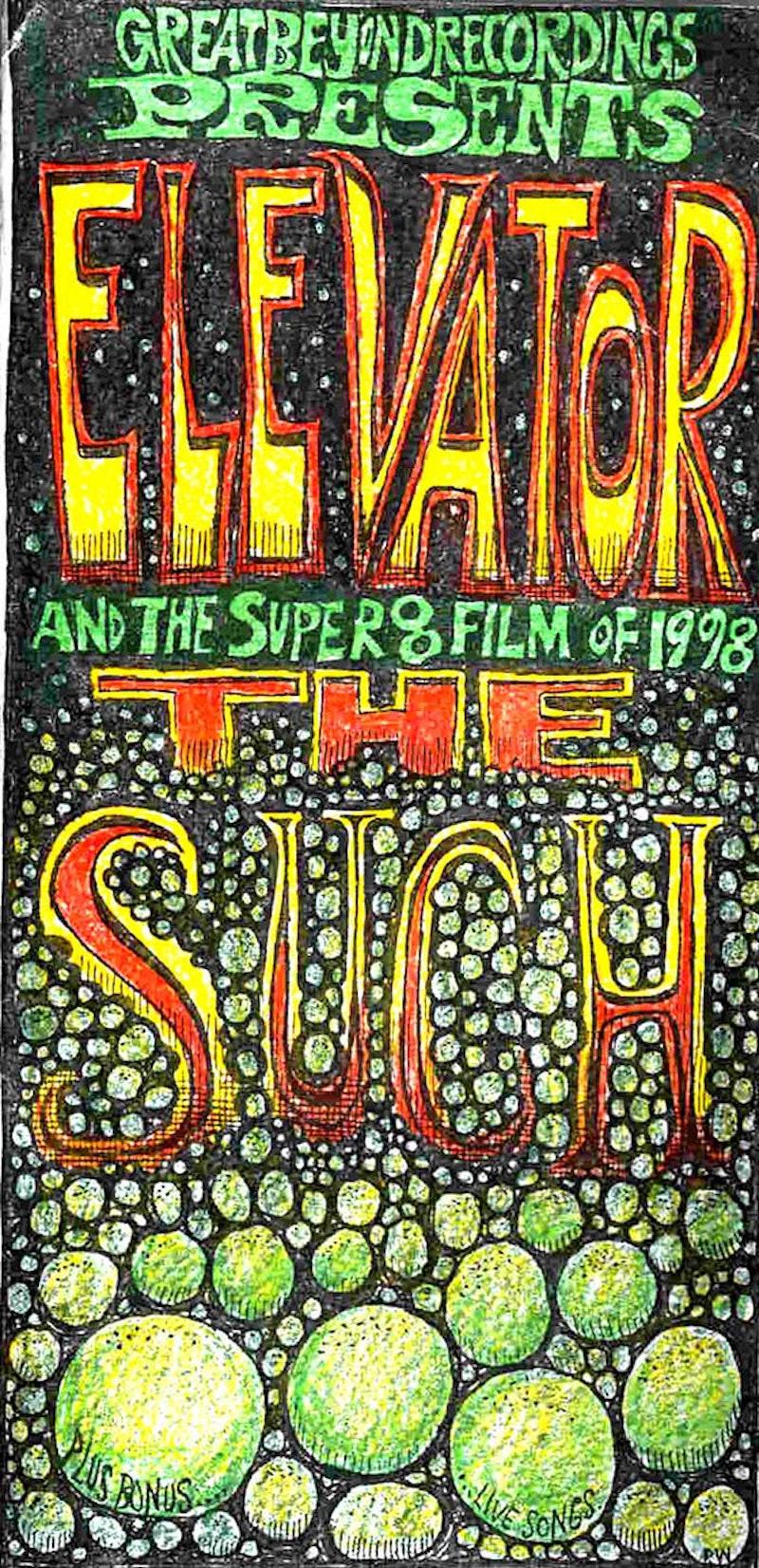

Eric’s Trip called it a day in 1996 but their outré approach to film lived on a few years longer. In 1994, Gaudet and White joined bassist Tara Landy White to form the intense psych-rock project Elevator To Hell, later known as Elevator. Under this name the trio starred in two chaotic/music driven films shot in and around the area of their Moncton, New Brunswick home studio. First came the murky short Deep Underground, a collection of footage taken by Andrew Fraser from 1998 to early-1999 and assembled and edited by White in late-‘99. This was followed by their magnum opus The Such. This disorienting work, crammed with hand-colored film and manic sloppy edits, was shot by the band with help from Michelle Noble and Chris Flanagan. It was produced and assembled by White from 1998 to 2004. Two versions of the film exist: one originally released as a VHS tape in 2000, and another that was completed in 2004 but only made public via the Internet in 2014. The 22-minute film feels like a montage of damaged home movies projected through an enchanted prism from a dimension beyond time and space. Elevator’s The Such is a cinematic monument to foggy memories and intimate catharsis.