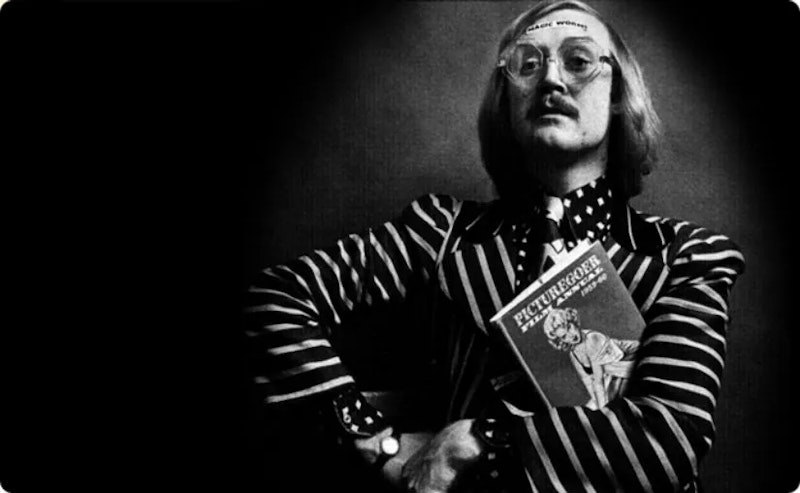

Vivian Stanshall was the lead singer, composer and multi-instrumentalist with the 1960s comedy outfit, the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band. He favored strange instruments such as the euphonium and the ukulele. The Bonzos reached the height of fame when they were featured in the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour film (1967) playing a song called “Death Cab For Cutie.” You can watch that here. That’s Stanshall up front, all six foot two of him, lank and lean, with ginger hair, moustache and eyelashes, doing a credible impression of Elvis Presley.

They had one hit single in the UK, “I’m the Urban Spaceman” (produced by Paul McCartney under the pseudonym “Apollo C. Vermouth”) which came out in 1968 and reached number 5 in the charts. It was untypical of their output, an almost straight pop song, written and sung by Neil Innes, the other composer in the band. The B side, “Canyons of Your Mind,” featured Stanshall doing another of his patented impressions of Presley. It included the immortal lines: “In the wardrobe of my soul, in the section labelled shirts.”

They were also the house band on Do Not Adjust Your Set, a children’s TV program featuring several members of what would later become Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Innes went on to have a successful career working with Monty Python. You can watch the entire collection of Do Not Adjust Your Set appearances here.

The band was formed in 1962 after a meeting between Stanshall and fellow Royal College of Art student Rodney Slater. They were originally called The Bonzo Dog Dada Band, which gives you an idea of their artistic intent. They changed it to Doo-Dah, they claimed, because they got bored explaining what “Dada” meant. Doo-Dah is an English expression meaning something like Thingamabob or Whatsit, a word you use when you can’t think of the name of something. It’s also a common term for the male genitals. They started off playing Jazz parodies from the 1920s and 30s, which they learned from old 78s acquired from charity shops and flea markets. Later, with the success of similar acts, such as the New Vaudeville Band and the Temperance Seven, they expanded their repertoire to cover all musical forms.

They were often compared to The Mothers of Invention. Like the Mothers, they had a theatrical, at times anarchic, stage show. Like the Mothers they employed visual comedy and utilized the studio to great effect. Unlike the Mothers, however, they weren’t musical innovators, preferring to parody previously established forms. They were also—to this Englishman’s ear at least—much funnier, with an anarchic, insightful, occasionally visionary sense of humor. That was almost entirely down to Stanshall, who rates as one of the most original comic minds of the 20th century.

They made six albums of varying quality. The first, Gorilla (1967) is a showcase of everything they’d learned to date, a glorious concatenation of comedy, satire, rock ‘n’ roll, psychedelic absurdity, show-biz parody and jazz. It was one of the first LPs I ever bought, and remains a favorite to this day.

The next, The Doughnut in Granny’s Greenhouse (1968), is more complex. It owes a lot to the Mothers’ Freak Out! The studio becomes a significant part of the process, with sound-effects, voice-overs and cut-aways. You can listen to the entire album by following the links here. A typical track is “My Pink Half of the Drainpipe,” which includes lines that could be understood as an introduction to Stanshall’s personal philosophy: “So Norman if you’re normal, I intend to be a freak for the rest of my life, and I shall baffle you with cabbages and rhinoceroses in the kitchen, incessant quotations from Now We Are Six through the mouthpiece of Lord Snooty's giant, poisoned, electric head, so there…’ He continued to baffle us with such insanity until his death in an electrical fire in 1995. He was 52.

By the time of the band’s dissolution, Stanshall had suffered a nervous breakdown. He was addicted to tranquilizers and was an alcoholic. He spent much of the 1970s on a drink-fueled bender with Keith Moon of the Who. You can hear Stanshall and Moon together here, playing the upper class Colonal Knutt and his sidekick, the loveable cockney-voiced Lemmy. The irony of this is that, despite his posh accent, Stanshall was from Walthamstow, a working-class part of London. His father had ideas above his station and beat that accent into him, which may account for some of Stanshall's problems in later life. He was always pretending to be something he wasn’t.

There are a number of solo albums, including Men Opening Umbrellas Ahead (1974), Sir Henry at Rawlinson End (1978), Teddy Boys Don't Knit (1981) and Sir Henry at N'didi’s Kraal (1984). There were collaborations with Steve Winwood, Eric Clapton and other luminaries of the day. He was the narrator on Mike Oldfield’s album, Tubular Bells. There’s also a complete comic opera, Stinkfoot (1985). It has only been staged twice and never recorded.

Finally there’s a film, Sir Henry at Rawlinson End (1980) starring Trevor Howard. You can see that here. Based upon the LP of the same name, it doesn’t live up to the semantic promise of the audio version. The charm of the album is that the characters are all played by Stanshall himself, and the action is described in wonderfully florid, descriptive prose. The joy comes from listening to Stanshall as he brings to life these absurd figures, each with their unique voice, their unique tone. The film, on the other hand, takes them all too literally and has the look of madness, as the protagonists all shout over each other as if continuing an interminable internal monologue out loud. No one engages with anyone else.

Here are the opening lines of the album: “English as tuppence, changing yet changeless as canal water, nestling in green nowhere, armoured and effete, bold flag bearer, lotus-fed Miss Havershambling, opsimath and eremite, feudal still and reactionary Rawlinson End. The story so far...”

It’s that “story so far” that indicates how he intends to proceed. There’s no plot. It’s made up of snippets of introductions to an ongoing radio serial we’re never going to hear. He explained his process in an interview with Toyah Wilcox in 1980:

“I would read the story so far: ‘Gwen and Maureen have become trampolining acupuncturists, and Bob is a gorilla and insists on wearing Dr Marten boots. Now read on.’ Now I never wanted to read on. I just liked the dot dot dot, and it was so provocative and exciting that I wanted to write things that were ‘the story so far.’ But the actual Sir Henry and the whole hierarchy, the whole family at Rawlinson End, were all parts of me talking to myself. I talk to myself all the time.”

The name “Rawlinson” preoccupied Stanshall throughout his recording career. It’s mentioned in passing on the Bonzos’ first album, on a track called “The Intro and the Outro” It comes up again on “The Doughnut in Granny's Greenhouse,” as Percy Rawlinson on “Rhinocratic Oaths,” before turning into something more substantial on their post break up, contractual album, Let’s Make Up and Be Friendly (1972). After that he continued to extend the saga in regular contributions to the John Peel Show, from 1975 till its last outing in 1991. You can hear that here.

It’s the essence of Englishness. It’s England made manifest in art. If you want to know what lies lurking, hidden, in the English psyche, listen to Sir Henry at Rawlinson End. The absurdity, the wistfulness, the sentimentality, the bombast, the pomp, the eccentricity, the ever-present class system: it's all there.

The music reflects this:

How nice to be in England,

Now that England's here.

I stand upright in my wheelbarrow

And pretend I'm Boadicea.

It's like an English version of Under Milk Wood, but with tunes: as if Tristram Shandy had shacked up with Dudley Moore in a pub outside Gormenghast and drunk too much scrumpy. I think you have to be English to follow it all, but the characters stand out in all their eccentric isolation, each mannered voice clearly delineated by Stanshall's remarkable vocal talents. You can't help but wonder what it might’ve been like inside his head, so full of chattering narratives, all struggling for expression.

Sir Henry is the central figure: loud and bombastic, always drunk, a stentorian aristocrat full of his own sense of self-importance. “If I had all the money I'd spent on drink, I'd spend it on drink,” as he says. Next is his brother Hubert, “in his forties and still unusual.” Wistfully deranged, there's one episode where he does bird impressions by standing on one leg and eating live worms from his pocket. And on: Old Scrotum the wrinkled retainer. Reg Smeeton, the human encyclopedia. “Did you know there's no proper name for the back of the knee?” Aunt Florrie, living dreamily in the past. Mrs E, the servant and cook, complaining about her lumbago. “Fried or fried dear?” Seth One-Tooth and the other denizens of the Fool and Bladder pub in the village. Madcap games and English eccentricity. Further away, the town of Concreton, the incongruous 20th-century conurbation which houses the working class. All of English life is here, exaggerated but immediately recognizable.

Some people love it. Others can't make sense of it. I gave a copy to my brother-in-law for Christmas one year. He loved it, but my sister was nonplussed and made a face like she'd just taken a spoonful of vinegar. It can have that effect. I think you have to have a literary bent to appreciate it. It’s full of puns and mad conceits, of references to other works of art, to 1930s radio serials and Saturday morning matinees, a jumble of vibrant madness from the mind of one man.

Vivian Stanshall was a unique voice in English culture. England misses him. We’re a poorer nation without him.