History rewrites itself in mysterious ways. Most people know that the late 1960s and early 70s were a great time for a certain mix of country, soul, early funk, and pop—Dusty Springfield recorded Dusty In Memphis, Bobbie Gentry did Touch ‘Em With Love, the Band followed in a similar direction. Elvis Presley is not usually included on this list, but he should be: though history may have written him out, the recent Elvis At Stax compilation shows that the King’s genre-bending recordings were as good as any. In addition, they were significantly more surprising, given that Presley had been close to irrelevant for a decade.

Critics like Greil Marcus view Presley’s early recordings for the Sun label as a holy grail: “If any individual of our time can be said to have changed the world, Elvis Presley is the one.” The post-Sun recordings served as inspiration for any number of 60s stars—both Keith Richards and Graham Nash, for example, can recall being floored by “Heartbreak Hotel.” But the 60s weren’t kind to Presley—or at least, his art. He spent time in the Army and appeared in a series of undistinguished movies, while the rockers he inspired articulated a counter-culture that made Presley seem tame at best, adult-schmaltz at worst. Presley could still draw crowds and turn heads; the man was (and is) an American institution. Institutions are often inflexible behemoths that maintain a status quo, and that status quo was out of style.

He could’ve just shrugged and continued on his way. Plenty of artists put careers on cruise-control before Presley; even more artists have since. But instead, he started putting out the best music of his career. He performed a comeback show in Vegas that melted most critics. He released the “Suspicious Minds” single: a huge, immaculate piece of country-soul-pop buoyed by light, flickering percussion—the kind of precise ticks that would hold together many an Al Green hit a few years later—and a series of rapid guitar fillips similar to those that pushed several country tunes from around the same time, including Kenny Rogers’ “Ruby Don’t Take Your Love To Town” and Glen Campbell’s “Gentle On My Mind.”

After that single came From Elvis In Memphis, the album that’s often presented as Elvis’s last gasp. It followed the sound of “Suspicious Minds,” embracing contemporary R&B more than the King ever had before, taking on country and soul songs with big bass grooves, a punchy brass section, and urgent delivery (supported by an orchestra, but so was a lot of soul in ’69, including southern-soul classics like Isaac Hayes’ Hot Buttered Soul). “It was the finest music of his life,” wrote Marcus of Presley. “If ever there was music that bleeds, this was it.”

On the charts, the last gasp was 1972, when Presley landed his final top five hit, “Burning Love.” And then, the decline of the 70s. Everyone likes watching someone larger than life brought down to size. The man gets paunchier, stretching out those iconic looks. Drugs play a bigger role in his public image. And he shows a fondness for sequined suits.

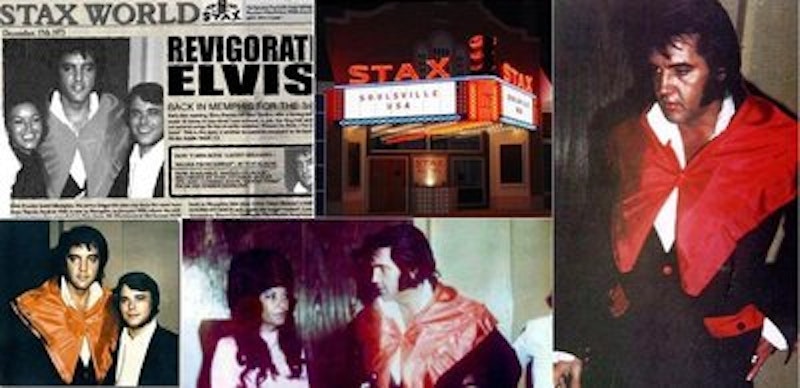

But the Elvis At Stax compilation shows that this is an overly simplistic story, one that ignores some of Presley’s more exciting recordings. He released a series of three albums in 1973, ’74, and ’75 that contained material recorded during two sessions at Memphis’s famous Stax studio in the summer and winter of 1973. Elvis At Stax puts the results of these sessions in one place, complete with snatches of in-studio banter and alternate takes.

The early 70s was a great time for musical interpreters, especially in R&B, where singers such as Hayes or Al Green recorded majestic re-workings of pop songs like “They Long To Be Close To You” (Hayes) and “Unchained Melody” (Green). Working at Stax, not with the house band who played on Stax’s many famous soul recordings, but with a set of musicians that Presley had worked with before (including James Burton, who had helped Merle Haggard add spark to his albums), Presley plunged into the ranks of great interpreters with gusto. The sonic territory was similar to From Elvis In Memphis, but looser.

You can hear this listening to a song like “If You Talk In Your Sleep,” which deserves a central place in the Elvis canon. It’s full of sudden dynamic shifts—horn slams detonating like they might for James Brown, sudden guitar down-strokes, funky lurches of electric key board. An especially deep horn keeps dropping fiercely and pulling the rug out from under the song with a few notes that work against the forward momentum. Shuddering strings and thick background vocals provide the atmosphere of a paranoia that might surround an illicit affair. But Presley’s vocals—one third plea, two thirds command—are dead serious. Either his lover is a sleep-walker (“if you talk in your sleep/don’t mention my name/if you walk in your sleep/forget where you came”), or he jumps every time he sees his own shadow. But he jumps with flair.

Flair also applies to Presley’s version of “Good Time Charlie’s Got The Blues.” “Everybody’s gone away/said they’re moving to L.A.,” he sings, as if he’s the only man left in Memphis (several Memphis musicians actually did pick up and leave to L.A. around the turn of the decade, like Stax’s Booker T. Jones). In the manner of “Suspicious Minds,” the song rides on gently ticking percussion and simple guitar. An organ accentuates the loneliness. Presley always did heartbreak well—full, sincere, tragedy in all-encompassing proportions—and when he sings the hook, “some got to win, some got to lose/good time Charlie’s got the blues,” he makes it seem like there are actually three categories: the victorious, the defeated, and then the people with the blues.

Artists often get mired in their own success. The weight of expectations, real or imagined, can make a singer write from a place of fear rather than strength; once overly-conscious of fans and history, he or she becomes trapped in a same-sounding rut. Most people can sell this for a little while, making small tweaks for two or three releases. But torpor is inevitable. Rust sets in. Habits harden into rigid structures.

Somehow, Elvis kicked back at that natural process of decreasing flexibility (and the decreasing returns that accompany it)—all while wearing a tight sequined suit. He embraced a different side of his sound, funkier and harder, but he also cloaked this move in strings and classic Elvis album covers so no one was overly alarmed. He hunkered down with songs he liked and musicians he knew. And he made some of his most interesting music, almost 20 years after he helped jump-start rock and roll.