In great art, one encounters a fusion of the expected and the unexpected, the familiar and the grotesque. The work of art, over the span of time when it grips our attention, goes places we couldn’t possibly predict in advance—but when it goes there, we say to ourselves, “Ah, yes, that’s fitting, that agrees with everything else so far.” Think of Marlon Brando, as the Godfather, dying among the tomato plants. Or the shock of hearing Mozart’s “Dies irae” for the first time.

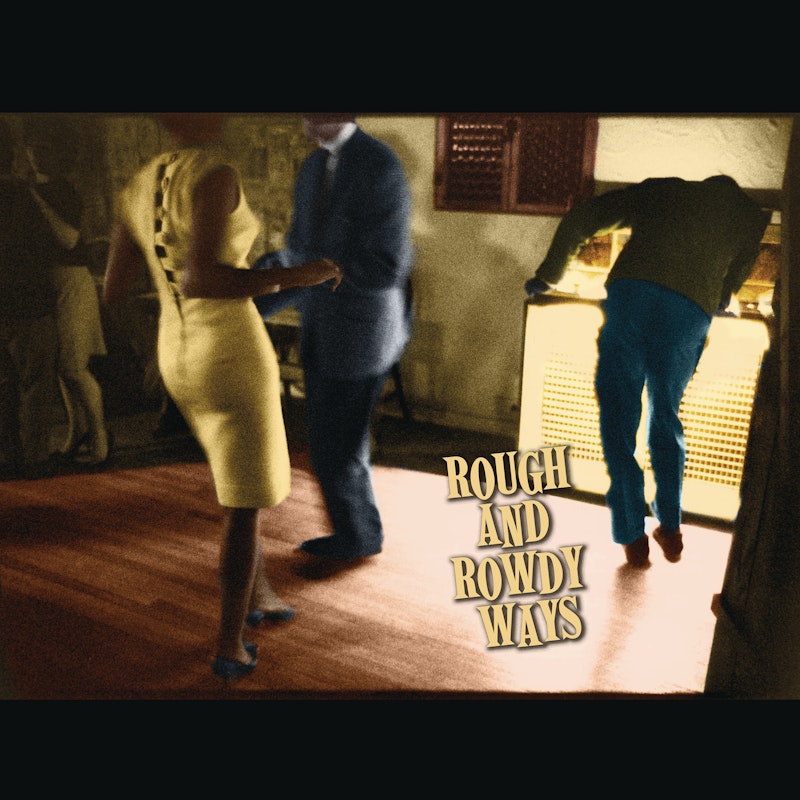

That’s precisely the mixture of old and new on Bob Dylan’s new album, unpretentiously titled Rough and Rowdy Ways. The songs are a further elaboration on a character we’ve seen Dylan play before, that of the sly jester speaking with prophetic undertones as he ambles through a fantasia of his own making. Ezra Pound, Casanova, and Brigitte Bardot used to walk around next to even stranger fictions inside Dylan’s head. Now he’s become a classicist, praising “the Pacino of Scarface” along with Chopin and “Anything Goes.” But even if the names he’s checking off lately are a little bit staid—there are no less than two separate references to Beethoven’s sonatas—his persona feels like it’s been let out of a cage. On “False Prophets,” he careens into a tirade of self-congratulation that’s funny and unapologetic:

I'm first among equals

Second to none

The last of the best

You can bury the rest

If that sounds familiar, it’s because it rings out like the best rappers hyping themselves. Dylan sits comfortably alongside new songs by J. Cole and Run the Jewels as an old bluesman who’s seen it all, heard it all, and hasn’t lost his touch. Plenty of his fans think of Dylan as “second to none,” but to hear him call himself that good is so shocking that it’s refreshing. For the first time in decades, Dylan’s made an album you can enjoy, not because it sounds like some brassed-up new version of old-timey music, but because it’s his.

In a pleasant way, this album does a lot to erase the boring, uneven work that Dylan has done in recent memory. It does this by realizing the aims of previous songs that almost worked, but didn’t have the energy or the emotional heft we’re all unconsciously thirsting to hear. There is, for example, a certain diminuendo blues effect that Dylan’s been mining for pathos ever since “Not Dark Yet,” on Time out of Mind. But when he uncorks it here, first on “I’ve Made Up My Mind To Give Myself To You,” and then again on the single (and coda) “Murder Most Foul,” the surrounding lyrics are strong enough to make it resonate:

If I had the wings of a snow-white dove

I’d preach the gospel, the gospel of love

In lines like these, Dylan seems resigned to “becoming who he is,” as Nietzsche would put it. And he gets there sounding more alive than ever to the possibilities of everyday life. In “Things Have Changed,” he was devilishly effective as an old dog who doesn’t care. But here, the same discontinuities lead him to a state of wonder:

Take me out traveling, you're a traveling man

Show me something I don't understand

I'm not what I was, things aren't what they were

I'll go far away from home with her

Dylan wants to see something he doesn’t understand. He wants to touch the hem of the mystery, and that earnest desire brings us very close to mystery ourselves as we listen. The music on the album goes along with this theme, echoing in uncanny minor keys like the truly weird songs of yesteryear (I’m thinking, for instance, of “Just My Imagination (Running Away With Me),” by the Temptations, or Wanda Jackson’s insane “Funnel of Love”). The plangent guitar on “My Own Version of You,” a Pygmalion story that’s both menacing and yearning, seems to be playing chords as old and primal as “Greensleeves.”

A lot has already been written about Dylan’s other final song (besides “Murder Most Foul”), the travelogue entitled “Key West (Philosopher Pirate).” It’s certainly enjoyable to see Dylan telling us how to read him, like a crazed circus promoter: “Look at me! I’m a philosopher-pirate!” But the song’s deeper than that. After I listened to it, I went back to Lipstick Traces, the book by rock critic Greil Marcus about avant-garde politics in the 20th century. Marcus quotes a now-forgotten group, the Lettrist International: “These knights of a mythic western were out for pleasure: a brilliant talent for losing themselves in play; a voyage into amazement; a love of speed; a terrain of relativity.” Their terrain was the city, and the goal was “to make a city where one could find what one loved, or find out what that was—to make a city where one could discover for what drama one’s setting was the setting... promising the solitary a festival.” Key West is clearly that city for Dylan’s solitary man:

Key West is under the sun, under the radar, under the gun

You stay to the left, and then you lean to the right

Feel the sunlight on your skin, and the healing virtues of the wind

Key West, Key West is the land of light

It would be too easy to say that Key West is a place in Dylan’s mind, like Desolation Row or the Gates of Eden. Then we could smile forgivingly at his desire to create a new frontier on the tip of the Southeast, after giving up searching for it in the great North woods. But fortunately what Dylan’s doing doesn’t reduce down to tourism or escapism. It’s not escapism if you really do escape. The paradise that Dylan’s carved out of Key West isn’t something easy to find; you can’t imitate his path without running a grave risk: “It’s hot down here, and you can't be overdressed/Tiny blossoms of a toxic plant/They can make you dizzy/I'd like to help you but I can't.” Instead of saying, “Go East, young man, and then turn south,” Dylan’s roadmap speaks to our power to make cities where “one’s setting,” the contingencies that shape us, are welcomed and redeemed. It’s worth going to strange places in order to find that kind of home. Dylan’s new album isn’t a treasure map that somebody else has thoughtfully prepared for you. It’s a bracing reminder of the need to draw your own.