Ye-Ye Girls in French Pop, by Jean-Emmanuel Deluxe, wants to bring attention to the women of French music, who captured the international imagination for a couple of years in the mid-1960s. “These girls ARE pop,” writes Deluxe, and he wants them to get the fame that status deserves. His book looks to “provide insight into what Gallic artists have to offer… especially as such artists are fairly unknown outside French territory.”

The author is certainly committed to his task. Ye-Ye Girls mixes French history with occasional interviews and discussions of the careers of a large number of French singers. It sometimes reads like a series of allmusic.com entries, offering several paragraphs on each member of a group of artists who comprised a scene. The emphasis is on career detail; there’s not much on sonics. Sometimes the author passes judgment on a song, album, or period in an artist’s career, but it’s hard to know how he arrives at his conclusions. He shoots from the hip.

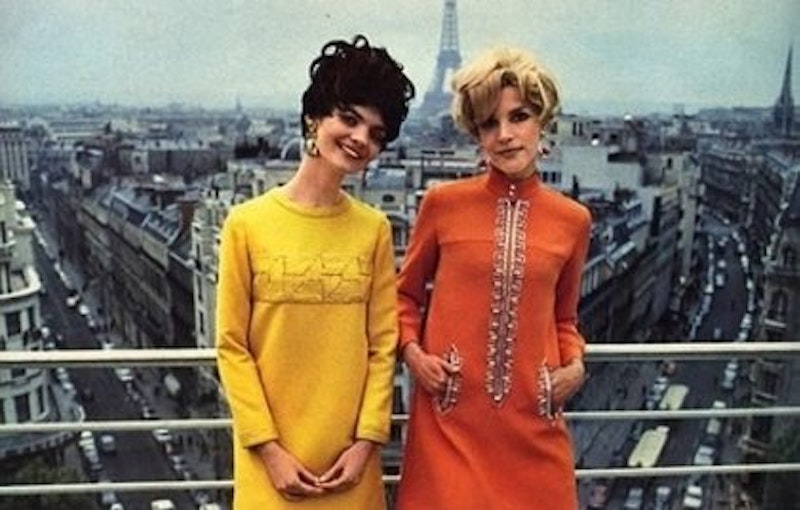

The book starts with Francois Hardy, Sylvie Vartan, France Gall, and Chantal Goya—“The Four Aces of Hearts.” Hardy is probably one of the best known Ye-Ye girls, due to her 1965 album The Yeh-Yeh Girl From Paris!, a tightly-crafted set of songs that mix girl-group pop, swinging jazz, and blues. (Wes Anderson used a song from the album, “Le Temps De l’Amour,” in his last movie, Moonrise Kingdom.)

The development of the Ye-Ye craze in France mirrored the rise in rock ‘n’ roll’s popularity elsewhere. “A milestone in rock assimilation,” occurred on June 22, 1963, when “a concert at the Nation… gathered no less than 150,000 teenagers…chairs were broken, shop windows smashed, innocent girls chased around.” At first, rock upset both the communists—it was tied up with Western capitalism—and the Catholics, because of its sexual content. But neither group stood a chance. A new radio show launched in October 19, 1963, one of the first French shows to play Elvis, Ray Charles, and soon, the Ye-Ye girls.

During the Ye-Ye craze, the French loved singers like Sylvie Vartan more than any international artists. When Vartan shared a bill with the Beatles, “the audience preferred her,” and fans commenced “booing the Fab Four and trying to get them off the stage.” Bob Dylan was so enamored with Hardy that at a performance in Paris, he apparently “quit the stage after just a few mediocre renditions of his songs… demanding that she come to chat with him in his dressing room, or he would refuse to go back and sing.” What’s more, “Once his whim had been satisfied, a pompous Robert Zimmerman would tell everyone he met "now I’m a star, when asking for the moon, I get the moon!’” Sadly, Dylan never turned that phrase into a song. When the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones and his girlfriend, Anita Pallenberg, met Hardy in England, they thought—or more likely, hoped—that she was interested in a threesome.

“The four Aces of Hearts” are just the tip of the iceberg. There’s a section on all the women who sang songs written by Serge Gainsbourg—probably the best-known practitioner of 60s and 70s French pop music on this side of the Atlantic. (He also sang an ode to Ye-Ye, “Chez Les Ye-Ye.”) He wrote for Vartan, Gall, Jane Birkin, Brigitte Bardot, and, surprisingly, Nico, before her days in the Andy Warhol-Velvet Underground crew. She worked with him on a tune for her 1962 movie Strip-Tease.

There’s also a chapter on English singers who crossed the channel and sang in French to boost their sales numbers. This group includes Petula Clark, Marianne Faithful, and Dusty Springfield, who all had some success singing in English (though it’s worth noting that the best work from Faithful and Springfield came later in their careers). Clark’s French sales seem beyond belief: “she released almost eighty EPs in France from 1958 to 1970, with each on selling an average of 500,000 copies,” which would put her at 40 million EPs sold. Even if that half-million number represents yearly EP sales rather than individual numbers, that would still be a remarkable six million EPs sold in France alone.

The book’s tone is light-hearted. Usually, this is endearing. There are exclamation marks everywhere—one part is titled, “We Loved The Pop Revolution So Much!” Sometimes, the author’s enthusiasm can overwhelm his critical faculties. He describes one Hardy album as, “overflowing with pearls… well the whole record was tremendous, in fact!” Okay! What makes it tremendous is left to the imagination.

Towards the end of the book, the author interviews Jacques Duvall, a French songwriter who worked with both Birkin and Gainsbourg. The author asks, “How would you explain why they [Ye-Ye songs] have lasted until today?” Duvall suggests that the question highlights “the very paradoxical essence of pop… Burt Bacharach, now much revered, was laughed at by critics at the moment when he was writing all his great classics. There’s no major or minor art…” The existence of this book proves Duvall’s point. Fifty years later, a relatively brief period of pop history gets a loving volume devoted to every detail of its existence.