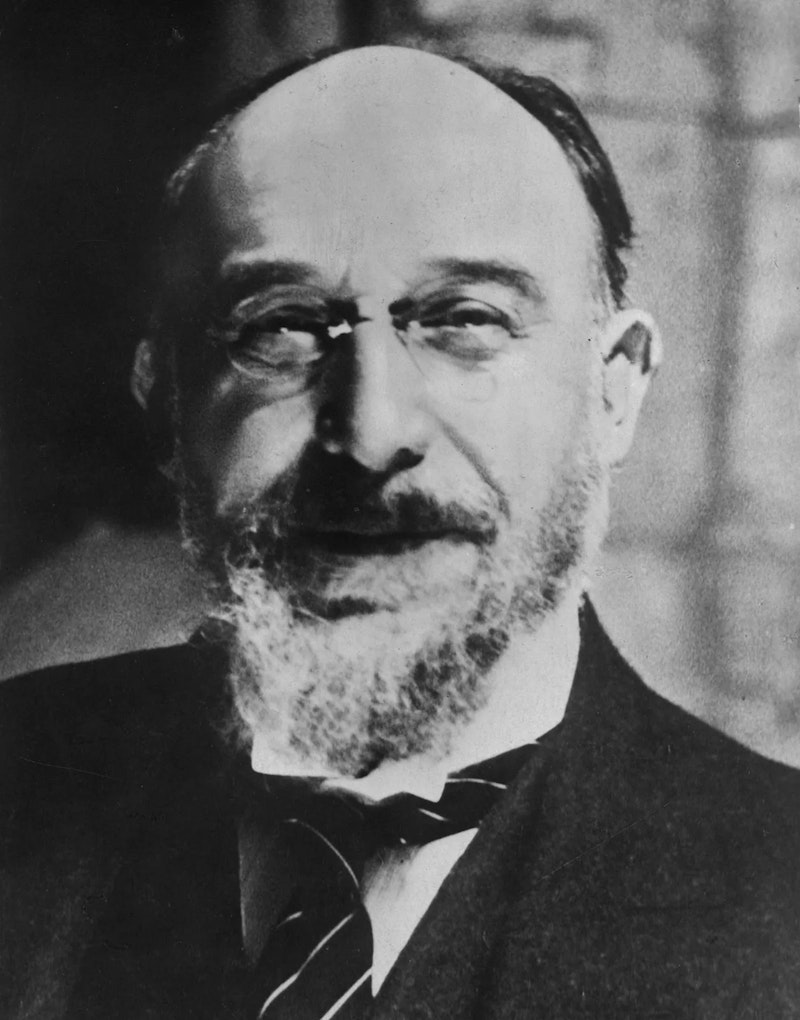

The French composer Eric Satie died 100 years ago on July 1, 1925. Strangely, there are few, if any, celebrations in his honor this year. I don’t know why: for a composer with a relatively small output, his influence on music history is immense. He had the honor, during his lifetime and posthumously, to be claimed as an influence for two major musical movements: Musical Impressionism and the Avant Garde.

The first to claim him as a precursor were composers like Debussy and Ravel, and then the Group of Six, who found in Satie an antidote to what they felt was the out-of-control pathos of Wagnerian romanticism. They believed Satie was able to create a full emotional experience with the simplest of means. Compare the 15-hour long Ring Cycle to the Gnossiennes or Gymnopédies.

Though short and repetitive, these pieces create an emotional experience. A listener changes moods from start to finish. Music can’t do much more than this. An example of Satie’s influence is demonstrated by the difference in the love scene in Tristan and Isolde by Wagner and that of Pelleas and Melisande by Debussy.

Where Wagner works the music up to a frenzy, Debussy goes for more subdued expression. This type of musical critique of an earlier work is legitimate because it stays in the domain of art. The rest is talk. Pelleas, like Tristan, is a beautiful work of art and whatever inspired it is legitimate.

A more dubious use of Satie was by John Cage. Cage weaponized Satie as a polemical figure. He focused on Satie’s use of time divisions and concentrated on certain remarks Satie used in his rare writings in which he downplayed what were at the time the lingering romantic ideals of music. Cage declared (in self-justification): “There can be no right making of music that does not structure itself from the very roots of sound and silence—lengths of time!”

Cage’s reading of Satie was reductive. Satie was concerned with musical time, but one could just as easily focus on Satie’s religiosity, the desire to place himself within the traditional current of Western Art (he went back to school at 40 to learn counterpoint and harmony) or even focus on his possible mental illness. He obsessively collected umbrellas, had fallings-out with everyone he knew and lived in a filthy dust-filled closet with two pianos stacked on top of each other, neither with strings. Satie liked word play, quips and pithy remarks; it’s hard to say when he’s serious or joking.

People like Satie’s music. He didn’t justify it; he just wrote it. There’s something about the subtle contrasts he uses that never get old. This suggests that listening should always be the measure of judgment used in musical appreciation. A situation where audiences could listen to a variety of styles and pieces of music and make up their own minds seems like the solution. The problem with the democratic process in music, however, is that many great pieces of music take time to get used to and in a society that demands instant gratification, they’d probably fall to the side.

I wonder what chances Satie would have if he was around today as an unknown and tried to get his music played? Consider the piano piece Vexations, which is a simple melody meant to be repeated 840 times and can last anywhere between nine and 12 hours. Was he serious or joking? Satie notes that the performer should “prepare himself before playing.”