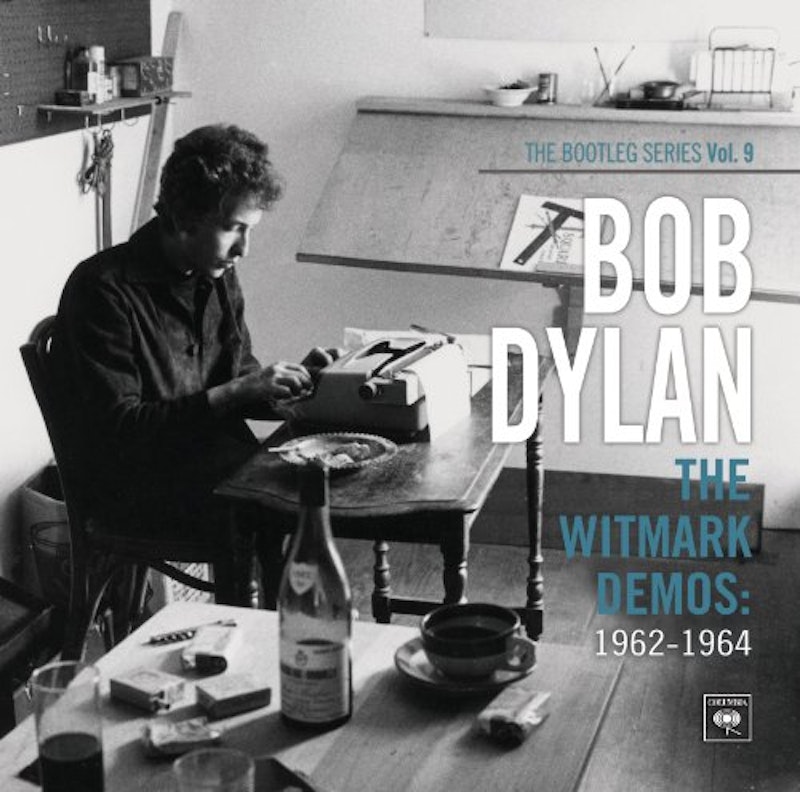

The Columbia vaults holding unreleased songs by Bob Dylan have been pillaged so voraciously that when a new “Bootleg Series” volume comes out, it’s mostly a ho-hum affair for even the most serious Dylan collector. I fall into that category—and like thousands upon thousands of fans, once scoured record stores for then-illegal bootlegs that were of varying quality and vinyl color—and, as expected, Vol. 9 of the slowly-parceled out series, The Witmark Demos: 1962-1964, contained no revelations.

(There’s a chance, of course, that Dylan and Columbia will make up for the lackluster 1975 official Basement Tapes release—the souped-version of “Too Much of Nothing” really burned me at the time—and the next “Bootleg” collection will be a three- or four-disc set that takes full advantage of Dylan’s hundred or so songs he recorded with The Band in Woodstock in the year following a motorcycle accident that laid the songwriter low. There’s no evidence that Dylan wasn’t banged up, yet it’s almost certain that he went into seclusion to escape the pressures of touring and take stock of his life and the month-by-month shifts in American pop and political culture.)

I’d heard most of the Witmark songs before, on various bootlegs, and the wan versions of “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “When the Ship Comes In” and “John Brown,” among the 47 songs, are fairly forgettable. This is all relative, of course, since it’s always enjoyable to get reacquainted with a song like “I’d Hate to be You on That Dreadful Day,” but it doesn’t compare to the release of the clean and audible Manchester concert of 1966 (Bootleg Series: Vol. 4), a powerful statement that Dylan, for a brief period, had no peer in rock and roll. Back in the early 70s, finding the boot from that show was like entering another dimension, as the opening number from his European tour, “Tell Me Momma,” simply explodes. There was also the brilliant howl of the once quiet acoustic Ric von Schmidt tune, “Baby Let Me Follow You Down” and Dylan’s speed-freak vocal on “Ballad of a Thin Man,” all of which more than made up for the uneven formal releases of New Morning and Planet Waves. When the spiffed-up, no-hiss recording came out in ’98, it was still hallucinatory and timeless, and I’m hardly alone in believing that no superior rock ‘n’ roll live performance exists.

Anyway, back to the dull Witmark, and there’s a catch. I ordered the CD from Amazon and received a “bonus” disc, a May 10, 1963 live recording of a concert given at Brandeis University (part of a folk festival), and though just 38 minutes long, it shatters the main attraction. At this time—pre-British invasion, months before JFK’s assassination—Dylan was just about to reach the height of his “protest” and “Voice of a Generation” phase, and though he’d soon dismiss his first batch of original compositions as a calculated career move, it’s easy to suspend disbelief upon hearing the angry, almost violent version of “Masters of War” on this record. The song is a Cold War artifact, but far more than a curio, and when he defiantly sings the last verse it’s hard to think that for at least on that night, Dylan didn’t mean every single word. I wonder if John and Bobby Kennedy ever listened to the song (the official and more tame version is on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan), and pondered if the following lyrics are directed at them, as well as Nikita Khrushchev and anyone in the defense industry or military: “And I hope that you die / And your death’ll come soon / I will follow your casket / In the pale afternoon / And I’ll watch while you’re lowered / Down to your deathbed / And I’ll stand over grave / ’Til I’m sure that you’re dead.”

Coincidentally, Greil Marcus, who has no peer as a Dylan historian and critic, has a new book out, Bob Dylan: Writings 1968-2010 and it’s a worthy companion to his excellent Invisible Republic (an exhaustive study of the Basement Tapes and the long-forgotten blues and country songs that informed Dylan’s writing) and Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads. Marcus begins by saying that the discovery of Dylan in the early 60s was directly responsible for his writing career and in the course of over 400 pages—articles culled from Rolling Stone, Creem, Salon, Interview, The Village Voice, The New York Times, Artforum, City Pages, The Believer and Threepenny Review, among other publications—he covers the entirety of Dylan’s canon in a style that’s alternately scholarly, glib, obtuse, contentious and always smart. The real attraction of this book, at least to me, is that Marcus’ columns, whether from 1970 or 1998, are not dated or stale; it’s like spending hours in your basement, rummaging through the boxes of old periodicals and personal correspondence you’ve collected over the decades. It’s likely that I have at least half of the articles in Marcus’ book, dusty and maybe waterlogged, so Bob Dylan is a welcome convenience.

As Marcus acknowledges in his introduction, there are contradictions in the book—over 30 years of writing about one musician will do that—but he stands by his writing. Doesn’t matter to me; it’s all fascinating. So, in a 1985 Village Voice piece he writes: “I hold no special brief for Bob Dylan as folk singer; he was great, but he was a better rocker, one of the four or five most piercing rock ‘n’ roll singers of all. In the mid-sixties, when he was chasing the Elvis legend, shouting onstage with his hands cupped around his mouth to make a megaphone against the roar of the Hawks behind him, there was more of Dock Boggs, Buell Razee, and other deep hollow singers in his voice than there ever was before.”

And then, from a talk given at Minneapolis’ Walker Art Center in 1988, he says this:

Bob Dylan came out of the tradition of the twenties and thirties blues and country singers […] No one, certainly no nice, middle-class, Jewish, ex-college student from Hibbing, Minnesota, every carried it off so convincingly. When Dylan sang the old blues song “Highway 51” on his first album in 1962, he made it real. The way Bob Dylan sang on his early records, he could have been born in Virginia in the seventeen hundreds, turned up for the Gold Rush in California in 1849, headed up to Alaska in the 1890s, made it down to Mexico in 1910—the road was the story, it told the story, the story told you.

Yet unlike so many of Dylan’s biographers and interpreters, Marcus is not uncritical about his ongoing subject, and laudably doesn’t traffic in gossip. He lampoons Dylan’s incoherent live appearances at various awards shows; skewers Street Legal; has little truck with the born-again records; and is mindful that Dylan chased dollars like most other performers. But in reading Bob Dylan, it’s hard to escape the feeling that Marcus, with layer upon layer of keen observations, isn’t dissimilar from the singer/songwriter himself, as he re-visits old songs, comes up with new critiques tempered by the passage of time, not unlike how Dylan could, in concert, completely alter the sound, and words, of familiar songs. It’s the best book I’ve read in at least six months, and if you’re motivated to buy The Witmark Demos, there’s really no excuse for not picking up Bob Dylan as well.