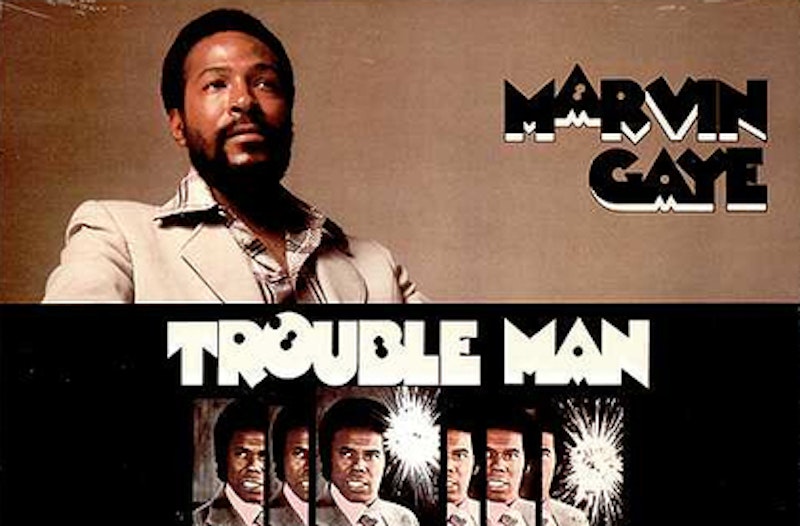

The original idea for this article was to write a brief rundown of some of the best blaxploitation film soundtracks around that have long outlived the images they were originally intended to compliment. Part of the inspiration came from a recent Numero Group release titled Brotherman by The Final Solution—a commissioned soundtrack that was actually recorded before the filming process had finished. When the plug was abruptly pulled on the whole project, what remained was a full soundtrack and no movie. Brotherman is nowhere near as resonant as soundtracks like Trouble Man (Dangerously cool arrangements by Marvin Gaye), Across 110th Street (Iconic soundtrack from Bobby Womack), or Cool Breeze (An extremely underrated gem from Solomon Burke). And I'm nowhere near as knowledgeable on the subject as some other fine music scholars—Blaxploitation Pride among them. But Brotherman does introduce an intriguing dilemma: the relationship between image and sound. It's not really a chicken and egg situation since both inspire one another. But unlike sound, which is present in almost all current cinema, film-inspired music is its own niche. The art of the "faux" soundtrack, whether explicit or not, is a tricky thing to master. Occasionally the limits of one medium confine the other. Other times, the work isn't substantial enough without an accompanying image. So how does one know when a sound needs a visual cue and vice versa? I'll give you a hint: it's not an exact science.

It's unfair to cast blaxploitation films as the norm for this discussion. First off, as my friend Sam would say, most of these soundtracks feature three tight tracks and a whole bunch of sound clips and scattered dialogue. So as much as I agree that these films constitute their own era, I do find a lot of them underwhelming, and, unfortunately, their accompanying images and story lines provide little substantial reinforcement. But they are an important resource when discussing the phenomenon of "detached" soundtracks.

Contemporary pop rock on the other hand has been consistently infatuated with creating the feeling of a soundtrack and has subsequently produced some memorable albums. Well into the 1990s, cinema served as inspiration for what have come to be some of the decade's most important albums. The Flaming Lips tapped multi-instrumentalist Steven Drozd for his heroin-induced musical revelations for years, but perhaps their most glorious conception came in the 1999 album The Soft Bulletin. By including two versions of "Race For the Prize" and "Waitin' For A Superman," the band bookends the album in a way that a filmmaker might reintroduce his film score or previous imagery in the final scene—the intention being to give the work a cyclical effect. This is only one of the ways that the album works on a cinematic level. It also helps that the musical arrangements are beyond dramatic. Instead of the accessible, radio-friendly pop that record execs were hoping for, a considerable amount of The Soft Bulletin is extravagant and grandiose to say the least. Just try to listen to a song like "The Gash" in a casual setting.

In 1996, The Olivia Tremor Control released its debut album, Music From The Unrealized Film Script: Dusk At Cubist Castle. With its concept embedded in the title, the album sweeps through 27 songs in about 70 minutes. Shifting between short experimental takes and more fully matured pop songs, Dusk at Cubist Castle certainly elicits the sensation of being at a movie. The 10-song "Green Typewriters" suite marks a noticeable break from the first half of the album, which, up until that point, is constructed on nostalgic, sun-soaked melodies. The suite culminates in the 9 1/2-minute drone experiment of "Part Eight" followed by the cathartic release of "Part Nine." But all the while, musical patterns and foreshadowing help to create a dynamic tension in the listening experience. The result is the sense that there are greater forces out there than just the musicians. So how does such a jumbled mess of Beatlesque melodies and quirky instrumental interludes stand on its own? It helps to have brilliant songwriting and instantly memorable tunes. Additionally, the shifting of rhythms and emotional keys provide a more acute sense of time and development. This isn't an album that consistently tugs at the same chord. It's organic. It changes direction and attitude as the playtime elapses.

Not every fake soundtrack works. One of the most recent failed efforts comes from the production team of Matt Edwards and Joel Martin who, under the pseudonym Quiet Village, released their album Silent Movie to a whole bunch of positive press. Whether it was out of irony or Avalanches-era yearning, people really seemed to be pushing the album hard, citing that it sounded like a film soundtrack. And in a way, the building blocks of Silent Movie are more cinematic than those of the albums we've discussed so far. Since the songs are comprised of hooks and samples from other records, the album's foundation is that of a personal collection. This concept of gleaning and recreating from source material was a foundation for the work of French new-wave filmmaker Agnès Varda. In Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse, a popular documentary that she made in 2000, the director focuses on the act of scavenging. Ultimately she identifies herself as a scavenger, and her work as a collection of stolen images and emotions.

In a review of Silent Movie I wrote, "The obvious goal in using a patchwork of disparate sources is to create something that sounds above the sum of its parts. But instead of mixing tempos and disassembling songs for minute details, Silent Movie is resigned to letting whole segments stretch on for minutes. Its lull pace and subtle to minimal alterations of source material fail to distinguish the album as a greater product." In short, Silent Movie needs visual aid. Its tracks are thin and lethargic in the way that a Mark Mothersbaugh number might get tiresome if stretched out to eight minutes in length. Without an image or a voice to help catalyze a transition, the album ends up sounding like mood music instead of encapsulating the whole event itself.

As I mentioned earlier, many blaxploitation-era film soundtracks have gained popularity while their visual counterparts have more or less drifted into irrelevance. Soundtracks like Shaft and The Harder They Come are immortalized for the music they've introduced. So is it a problem that these songs are so often detached from their original purpose? Of course not. It just illustrates, on one hand, the wealth of creativity from those working on the musical side of these pictures (Besides, the music was the driving force for almost all of these movies) and on the other, the ability of one medium to act as two. The style and imagery of these films can visually be seen through the music. Just listen to a song like "Are You Man Enough" by the Four Tops, which was a centerpiece for the film Shaft in Africa. The vocals are tense and powerful, embodying Shaft's persistence and exceeding manliness. The dramatic opening chords and rapid conga beats give the impression that time is fleeting and that evil lurks around every corner. Simply put, the music is illustrative, effective, and adaptable. It provokes a visual sensation all on its own, which in the end, is what one should expect from their music.