Blonde on Blonde, a double album that “begins with a joke and ends with a hymn,” has produced more ink, pixels, and stoned diary entries in its wake than most records over 50 years old. Daryl Sanders, a Nashville music journalist, has a new book out about the recording sessions that took place there over only eight days in early-1966. It’s titled That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound after Dylan’s famous description of the elusive sound he was looking for in the mid-1960s, a phrase that only came to him 12 years later. The fact that the man behind this couldn’t describe it for so long speaks to the album’s depth, ambiguity, and lyrical and musical accomplishments. Dylan—only 24—at the height of his amphetamine addled powers, a group of virtuoso Nashville session musicians, and the impeccable guidance of producer Bob Johnston realized that quicksilver sound in such a short amount of time it still boggles the mind. No wonder there are still books about it published and outlandish archival releases flowing out of the vaults.

I was worried Sanders’ book would mostly re-hash familiar anecdotes from secondary and tertiary sources: how Dylan kept everyone waiting as he finished the lyrics of “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” and didn’t tell any of them that it was an 11-minute song; how many songs are about Edie Sedgwick, Nico or Sara Lownds; or the volatile tour with the Hawks that preceded recording, where Dylan and his band were getting booed for “playing it fucking loud.” The book is slight at only 200 pages, but once Sanders is done setting up the scene, it gets really good. I love books like this that hyper focus on famous recording sessions down to the hour. Sanders writes about every single rehearsal, false start, incomplete take, alternate versions, and keeper cuts with exhaustive detail—it’s fantastic.

After dispensing with the obvious, Sanders goes day-by-day as recording begins. As most Dylan fans know, Blonde on Blonde was begun in New York with half of the Hawks, Al Kooper on organ, Phil Griffin on piano, and Bobby Gregg on drums. It was a mess, and the only song to survive from the aborted New York sessions was “One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later),” a thrilling standout and one of Dylan’s personal favorites. They nailed the master take in the early hours of January 26, and immediately afterwards, Dylan went up to 62nd St. and made an impromptu appearance on Bob Fass’ Radio Unnameable. He went on air at 1:30 a.m. and “took calls from thirty-eight listeners over a two hour stretch.” I never knew about this—I’d love to hear a recording if anyone has it.

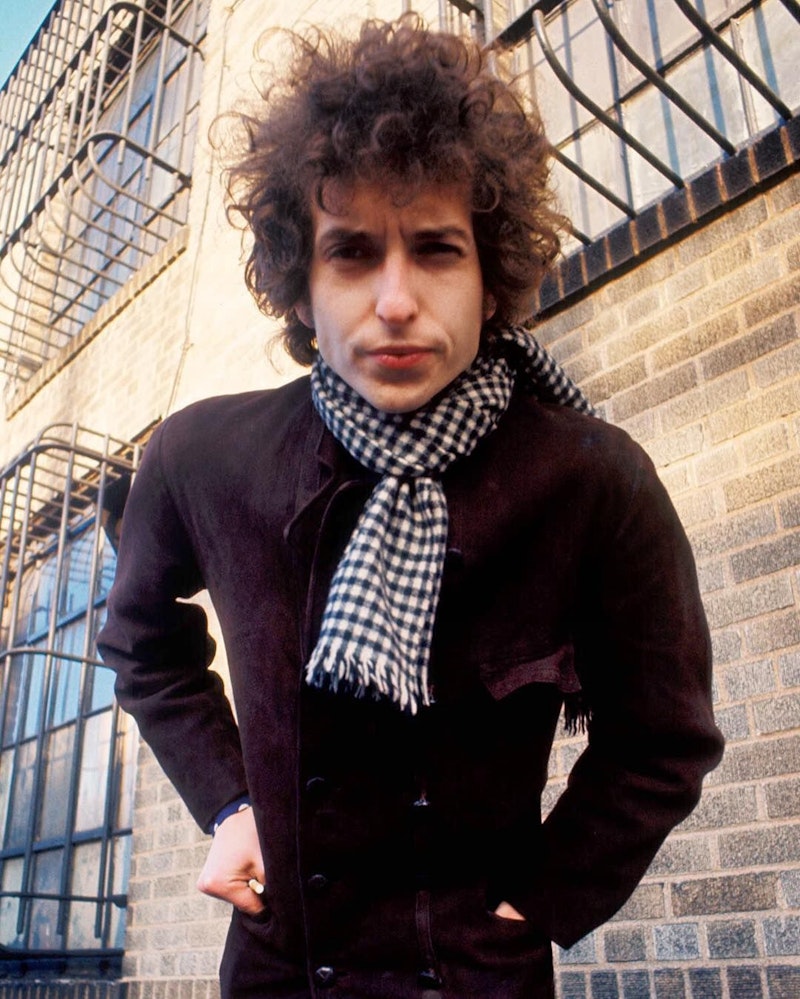

Jerry Schatzberg shot the iconic album cover on February 8, the coldest day that year in New York. The blurriness wasn’t an aesthetic decision or drug reference; they were both just really cold. A happy accident: the cover’s ambiguity was perfectly of a piece with the album’s elusiveness elusive. Sanders frequently returns to the songs’ prevailing themes: “gates” and “waiting,” words that appear in nearly every song. Robyn Hitchcock, a Dylan devotee, says that Blonde on Blonde “had a sort of double title, it really implied that it was a double world. It sort of has a unified sound, and it almost doesn’t begin and end. I mean, it obviously ends with ‘Sad-Eyed Lady,’ but you could simply kind of go round and round inside it… It’s a point of view, I suppose.”

Onto Nashville, with Wayne Moss, Mac Gayden, Robbie Robertson, and Jerry Kennedy on guitar, Kenneth Buttrey on drums, Joe South on bass and guitar, Al Kooper on organ, and Hargus “Pig” Robbins on grand piano. Not everyone appeared on every song, and people would show up for a song or two, sometimes summoned in the middle of the night like trombonist Wayne “Doc” Butler, who was woken up by the call for “Rainy Day Women” just after midnight on March 10. He came over in a fresh suit, clean-shaven, and was done within an hour and a half.

More familiar anecdotes: Dylan keeping the players up for hours on Columbia’s dime, cutting tracks from four to seven in the morning. This is the case for all of the album’s red-letter songs: “Visions of Johanna,” “Stuck Inside of Mobile,” and “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” They rarely began work before midnight, with Moss telling Kooper at one point: “That hour of sleep I got last night is getting pretty lonely.” They couldn’t nap, because who knew when the speed freak voice of a generation would summon them down from the lounge? Given the conditions, it’s remarkable how impeccable the playing is throughout Blonde on Blonde, and a true testament to the players’ intuition and abilities.

After finishing “Leopard Skin Pill-Box Hat,” McCoy turned to Robertson and told him, “Robbie, the whole world’ll marry you on that one.” Robertson had gained the respect and trust of the Nashville players by bringing a vicious approach to the blues that no one else in town had. He wasn’t “stepping on anyone’s toes.” Same goes for “Pledging My Time,” a song I never really cared for but is exactly the type of song that benefits from knowing the circumstances of its recording. Bluegrass musicians Peter Rowan and Richard Greene sat in on the “Pledging My Time” sessions, and I can only echo their disappointment: “There’s so much that can be done,” Rowan says, “I don’t know why [Dylan] keeps using those same old chord changes and melodies, you know, old rock and roll things over and over again,” with Greene adding that he thought the song was “abominable… I was really surprised by the low quality of the music. I mean it was just, it was amateurish.”

Readymade blues rock sounds even more boring today, but most of the album is still difficult to classify or categorize. It doesn’t even sound like the other two in Dylan’s electric trilogy. Rock critic Dave Marsh contends that Blonde on Blonde “is a much more realistic record than Highway 61… You weren’t going to run into anybody from ‘Tom Thumb’s Blues’ on the street corner. You were definitely going to run into ‘Just Like a Woman’ on the street corner.” Ironically, this doesn’t apply to the most pop song on the record, “I Want You,” the last master take cut for the album at the end of a marathon session where they racked up a relatively remarkable six complete songs.

Some things I never noticed or knew: Dylan flubs a line in the master take of “Stuck Inside of Mobile,” singing “When I he built a fire on Main Street,” an accident unaccounted for in the wake of the song’s relentless drive forward; Dylan wrote “Just Like a Woman” in Kansas City on Thanksgiving Day 1965; Robbie Robertson does not appear on “Visions of Johanna,” it’s Jerry Kennedy playing those caustic blues licks that accent and respond to Dylan’s vocal throughout the song. Sanders also finally clears up the confusion as to Blonde on Blonde’s release date, officially listed as May 16, but given circumstantial evidence and extant press materials, there’s no other day than June 20 that the album could’ve come out. Sanders suggests The Beatles were inspired by the loose, carnival atmosphere of “Rainy Day Women #12 & #35” for their own “Yellow Submarine,” which is also full of sound effects and people talking and laughing in the background. There’s no way The Beatles didn’t hear the song before they recorded “Yellow Submarine,” as “Rainy Day Women” had just peaked on the U.K. charts.

Blonde on Blonde remains a useful blueprint for the concept and sprawl of the double album, a format where the artist is able to stretch out and try a variety of things that would never make it onto a single LP, especially when you’ve got one song taking up a whole side. But unlike The White Album, Tusk, or Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness, Blonde on Blonde has a unified sound, a lithe chrome mask coating every song, a through line that connects such disparate compositions as “Fourth Time Around,” “Leopard Skin Pill-Box Hat,” “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands,” and “I Want You.” Only the latter sounds like it was recovered from another session, another city: it rings and glistens unlike anything else surrounding it, propelled by Kooper’s sublime organ playing and Moss’ astonishing 16-note runs leading into every chorus.

The well is drying up when it comes to Dylan’s most acclaimed period in the mid-1960s. But That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound gives life and image to the making of Blonde on Blonde, and takes less time to read than listening to the unabridged The Cutting Edge entry in the Bootleg Series. Read this book if you care more about piano trills and studio work than blind speculation on the possible subjects of Dylan’s lyrics. I don’t care about Edie Sedgwick, I want to know where Dylan was when he first started “Freeze Out” and who contributed what to one of 20th century’s most enduring works of art.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith