The town of Madison, in West Virginia’s Boone County, was home to the musical oddity named Hasil Adkins. It’s the doorway to coal mine country plus the locale of a rich fabled Appalachia history. Adkins went by many monikers throughout his colorful if not so illustrious career: The Lone One, Hasil & His Happy Guitar, The Madison Madman, the Wild man of Boone County and The Haze. His sound was dubbed psychobilly, cowpunk or hellbilly, and was the originator of the Chicken Walk dance craze and another called, Do the Hunch, a code name for sexual proclivities. I've made numerous mentions of Adkins here and elsewhere mostly because he was such a unique, strange and unusual talent of dubious distinction. I was a fan before we hung out and toured together.

In the early years, Adkins was known as a rockabilly musician. An unconventional rock/blues/country outsider musician still doesn’t define him. He could improvise and compose surreal song lyrics at random. One title is “Peanut Butter Rock & Roll,” about eating peanut butter sandwiches on the moon. “No More Hot Dogs” depicts decapitation of a girlfriend, hanging her severed head over the bedpost so she won’t eat more hot dogs. “She Said” is about waking up one morning to a lover, comparing her to a dying can of commodity meat. His tunes of lost love, aliens, heartache, chickens, dinosaurs, cats and the police are funny and frightening.

It’s hard to define his music and may confound many casual listeners. His output of recordings on vinyl 45’s was maybe a dozen titles over a few decades starting in the late-1950s and early-60s. His first known record release was in 1962, “Chicken Walk / She’s Mine.” Adkins was a popular local party fixture in Boone County. He was well-loved and recognized in the surrounding areas of backwoods roadhouses, honkytonks and beer joint shacks that dotted the rural coal towns and farms.

It wasn’t until the 1980s he garnered cult status among punk and rockabilly connoisseurs. The legendary Norton Records (Red Hook, Brooklyn. N.Y.) founders Billy Miller and Miriam Linna recorded and released a number of vinyl albums, 45’s, EPs and CDs with Adkins as a frontrunner among the Norton label’s many artists. Hearing the Adkins song “She Said” also piqued the interest of a punk/psychobilly band The Cramps. Front man singer Lux Interior and guitarist Poison Ivy liked it so much they reissued the original 1964 song, making it their own. In the process they solidified Adkins as a reigning pioneer in that weird sub-genre world of rock ‘n’ roll gone berserk. It certified “The Haze” with newfound success into the 21stCentury until his death in 2005, a few days shy of his 68thbirthday.

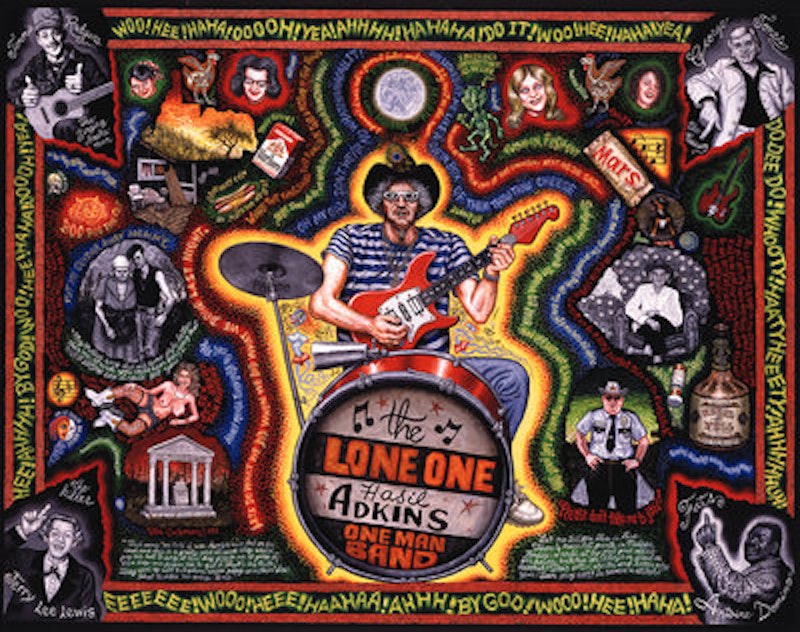

The painting of Adkins (1993) pictured above is by Joe Coleman. It depicts the story of Adkins’ life in a series of graphic vignettes. Coleman was also a good friend of mine and was the one who gave me Adkins’ phone number. It was shortly after that I made road trips back and forth to Boone County. I delivered Adkins to Baltimore and New York for gigs where we shared the stage. Adkins wasn’t a complicated man yet he was deeper than most. People couldn’t understand his West Virginia drawl but I could comprehend him. I’m not sure why we got along so well. It was always rumored he could be extremely difficult and easy to fly off the handle, prone to violent fits of rage. I never witnessed anything like that.

Adkins grew up surrounded by poverty and barely had a formal education. Yet he was wise when it came to songwriting and lyrical wordplay. He was an unstable genius doing it in his own way. There was a claim he wrote close to 7000 songs. A boast where he was quoted as saying something to the effect of, “I got about 6037 songs I wrote myself.” Anyone with half a brain would know he was joshing. Hearing him sing an old cover tune like “In the Pines” could melt your heart. Another memorable favorite was “Leaves In Autumn.”It will surely bring tears to a sorrowful eye.

He lived and died down in the holler near the childhood tarpaper shack where he was born. A simple man living an even simpler life of song, until he was run over by a meth-crazed, vodka-fueled kid on an ATV in front of his trailer in 2005. It’s true he liked to play with guns and drank more than a little. He was a hobo poet straight out of the 1950s with fast cars and faster women. Another Boone County legend, Jesco White The Dancing Outlaw, said of Adkins after the funeral, “ He was a tough ol’ booger… I’ll tell you that.” Hank III said,” Words cannot describe how much Hasil’s style has influenced my own music.”

The day they put Adkins in the ground there was a torrential downpour during the burial service. The graveyard in nearby Danville was getting very muddy and there was fear of flooding. How fitting if his casket was carried away in a flash flood river of rainwater. Raging like a toxic tire fire behind an abandon gas station. The ramshackle doublewide trailer with a gaping hole in the floor. A yard full of rusted junk cars, smashed windshields glistening in the noonday sun. An old broken guitar hanging on the wall.

In 2018 Hasil Adkins was inducted into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame.