This is part of a series of posts on 1960s comedies. The previous post on The Nutty Professor is here.

Action/comedy in the 2000s is a genre that’s been market-tested and perfected. Films like Deadpool, Thor: Ragnarok and (earlier) the Ocean's heist films have an action chassis, and then they throw in gags and funny bits. The action and the comedy exist essentially in parallel. You have an exciting plot, with explosions, chase scenes, twists, and a protagonist who self-actualizes and/or gets the girl. But you also have witty quips, banter, and a bit of absurdity, like a character played by Julia Roberts disguising herself as Julia Roberts in Ocean's Twelve, or Deadpool's crack superteam all getting instantly killed in Deadpool 2. The goal is to give viewers the satisfaction of both chuckles and standard action resolution.

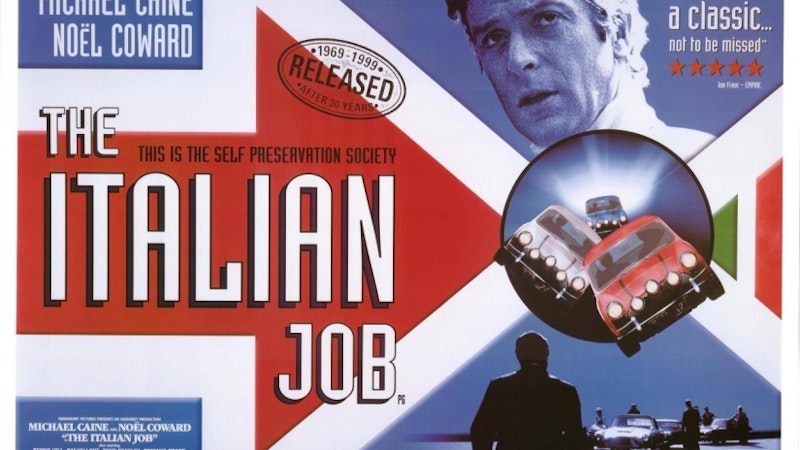

The Italian Job (1969), directed by Peter Collinson, works differently. It does have action set pieces and gags. But the biggest gag is that the action plot never really works. Instead of showing you exciting derring-do, the film keeps tripping over its own feet, and stumbling face-first into cream pies. The hero does not self-actualize, and there’s no triumphant catharsis. The film is one big, hip pratfall, set to a fantastic music score by Quincy Jones.

The plot that doesn't features Charlie Croker (Michael Caine) a master thief who’s just gotten out of prison. On his release, Croker immediately sets about working on a huge job in Italy, enlisting the help of the still imprisoned criminal maestro Mr. Bridger (Noel Coward) to provide funding and resources. Croker organizes a gang to steal a gold shipment in Turin by hijacking the cities traffic computers and escaping in the ensuing gridlock and chaos.

All the elements are in place for a satisfying action romp. But that's not what happens. Croker doesn't ever gel as a raffish man of action. Instead, he's a philanderer and querulous jerk. His flighty girlfriend, Lorna (Maggie Blye) buys him a roomful of prostitutes to celebrate his release, and then gets into a fight with him when she discovers girls she hadn't gotten for him in his room later. The two have a battle involving a giant squeaking teddy bear. Lorna cheats on Croker too (to get out of going to prison over stealing the Iranian ambassador's car) and their relationship never gets resolved in a satisfying action-movie bow. Croker sort of declares his love for her in Tunis, but mostly it seems like the does so to get her to go back home to England. She waves at him enthusiastically as she departs, while he covers his face in embarrassment.

The preparations for the heist are similarly fumbled. Croker's team keeps incompetently destroying cars in their practice session ("You were only supposed to blow the bloody doors off!" has become the film’s most famous line.) To get in touch with Mr. Bridger, Croker breaks into the prison bathroom. You don't see how he does it, which would highlight his competence and action-hero ingenuity. Instead, you’re just presented with scenes of Croker and Bridger huddling together in the stall, with Coward looking incredibly sour.

When Croker's team finally heads to Italy, they're stopped on a mountain road by the Italian mafia, decked out in evening clothes and standing silent on the Alps. Croker and company get out of their cars to talk to them, and the mafia has a giant earth mover crush and then push each vehicle over the cliff, with lingering shots of the cars smashing apart on the descent. Croker then issues an absurd nativist threat that if the mafia kills him and his team, Mr. Bridger will retaliate against the Italian population in Britain. "Every restaurant, cafe, ice-cream parlor, gambling den and nightclub in London, Liverpool and Glasgow will be smashed," he says. Is he bluffing? Who knows? The story goes trundling on, unconcerned.

Once in Turin, Croker spends most of his time yelling at his men, who are perpetually distracted, arguing in one scene that they can't ride in the back of the van because of various complaints such as migraines and asthma. The last third of the film then dissolves into a preposterous, endless car chase, in which three Mini Coopers laden with gold whoosh about the city and around the tangled traffic. They shoot down boulevards and through viaducts with sporty gumption as Croker lambasts his driver for not driving fast enough.

The car chase is partially set to "Self-Preservation Society," a tune sung by members of the cast in Cockney rhyming slang. Scenes of the robbers escaping are juxtaposed with a ostentatiously choreographed celebration back in the prison, where the prisoners bang plates in time to the music to honor Mr. Bridger, who acknowledges them with royal waves (he's obsessed with the Queen). The film turns into a music video, the plot tumbling off down the ravine to be replaced by a celebration of composer Quincy Jones' tongue-in-cheek cool.

The Italian Job's end is a cliffhanger. After they've escaped the police, our heroes drive their getaway bus too fast, and it skids out, hanging over a mountain abyss. The gold is at the far end of the bus, its weight threatening to tip them all over. Croker tries to pull the bars back to the other end and safety, but it keeps sliding away from him. He declares he has a plan—and the film ends.

There was talk of an Italian Job sequel that would’ve resolved the conclusion, but it never materialized. Instead, as it is, the Italian Job's finish is more like the deliberately unsatisfying dead end to Monty Python and the Holy Grail than like the action/comedies of the 2010s. The comedy isn't in any particular gag, but the refusal to take the action movie tropes seriously. The narrative is so dumb the film can't be bothered to finish it. Croker and his buddies are all jerks anyway; who cares if they die? The main regret is that you don't get to see the bus fall over the cliff and smash apart.

The Italian Job is a joy in part because it recognizes the action movie as nonsensical comedy. But its real brilliance is that by turning action into comedy, it purifies the action. All the detours and hip music sequences filter out the more sententious, brow-furrowing parts of the action genre. There're just some fun explosions, a ridiculous chase, and the visceral pleasure of cars smashing apart against mountainsides.

Instead of adding gags to his action film, director Collinson treats action as a gag—a pure punchline, enjoyable for itself rather than for any advancing plot. It feels good—especially when Quincy Jones scores it.