This is part of a series on 1980s comedies. The last entry on Hollywood Shuffle is here.

Charles Schulz's Peanuts is perfect. I just read a volume of the collected comics from 1989-1990, a period that’s generally thought of as one of the strip's low points—and it’s still an incandescent triumph of fuddy-duddy genius. In some ways the strip got even better as it went along. Schulz over time abandoned the punch lines and physical humor relied on by lesser cartoonists, writing strips that simply meditate on odd words or phrases, or which wander around emptily before settling to rest like a deflating balloon. "She's cute isn't she," Charlie Brown says to Linus as they stand by the bus. "Cute isn't everything, Charlie Brown," Linus replies. "I fall in love with any girl who smells like library paste." That's the joke; there’s no further explanation.

I've heard people argue that Peanuts is sappy, clichéd, precious, or predictable. "What are these people reading?" I think. Have they seen the extended sequence where Charlie Brown grows a baseball stitching rash on his head from stress, and has to go to camp for a break, and wears a bag over his head to hide his disfigurement, and then everyone at camp loves and respects him, until he’s finally cured and takes off the bag, and they realize he's a loser? How can you read Peanuts and not love it?

I now have an answer of sorts. It's easy to hate Peanuts if you haven't read the strip—and instead watched the atrocious animated 1980 feature, Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown (and Don't Come Back!)

As far as I could tell from the credits, Schulz had no creative input on Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown, and it shows. In the comic strip—and in many of the earlier animated features that Schulz oversaw—the narratives are built around trivial nonsense that spirals into gloriously neurotic knots. In one sequence from that 1989-90 volume, for example, Linus muses about how he's learned to tie his shoes automatically—and then, because he's thinking about it, he forgets how. The next week of strips is Linus wandering around helplessly without shoes.

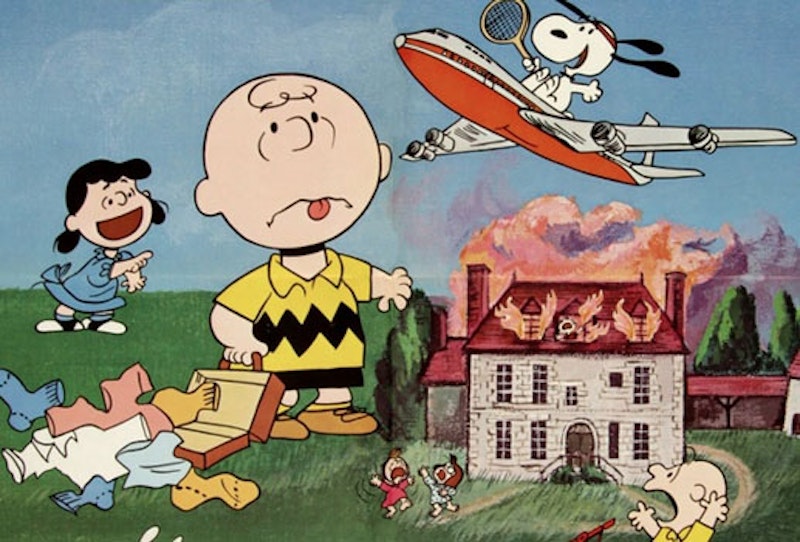

In contrast, Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown, tells a story with an actual plot. Charlie Brown, Linus, Peppermint Patty, and Marcy are selected as exchange students in France for two weeks, with Snoopy and Woodstock improbably tagging along. Charlie Brown in particular is invited to a Baron's castle. They arrive and find nobody home, though, because the invitation was from the Baron's granddaughter; the Baron himself hates meddling kids. Eventually Charlie Brown and Linus get in the house, and find out that Charlie Brown's grandfather had a minor flirtation with the girls' grandmother when he was in France during the war. The castle gets set on fire, Charlie Brown and Linus rescue the girl, the Baron feels sorry for being such a jerk, and everyone eventually goes back where they came from.

It's as if no one involved in producing the cartoon ever read a Peanuts strip. The whole point of Peanuts—the foundation on which the series was based for 50 years—is that Charlie Brown is a sad sack who never wins. When he runs to kick the football, he misses and falls flat on his back. When he goes to the mailbox on Valentine's Day, all the hearts are for Snoopy. His loves are unrequited; his baseball games are losses.

But in Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown, Charlie Brown is chosen to go to France; he gets a letter from a cute little girl; he saves a house from burning down. He's not a loser at all. He's a fairly typical protagonist. Rather than the humor in the film coming from the world dumping on Charlie Brown, the jokes are mostly gentle slapstick, especially involving Snoopy. The beagle gets thumped with tennis balls at Wimbledon and gets into fender benders in France. But the truth is that even the beagle is normalized. As my son noted in horror, "They go to France and Snoopy doesn't even fight the Red Baron!" The loopier aspects of Snoopy's imagination are carefully trimmed out, and replaced with standard issue sight gags, executed without any particular vim or grace.

The result of draining Schulz's genius out of Peanuts is flavorless, maudlin goo—comedy without bite, melodrama without pathos, narrative without purpose. Though the film is only 76 minutes, it feels endless—there are multiple scenes of the kids driving nowhere in particular, past indifferently drawn and animated vistas of the French countryside. The script serves a stream of cutesy kid conversations devoid of punch lines, and even more devoid of Schulz's weird anti-punch lines.

The film's awful, and a testament to Schulz's particularly idiosyncratic genius. You only fully appreciate how weird Schulz was when you see the hapless creators of Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown trying to fit him into a semi-standard movie plot. You can see them flopping around helplessly. "Where's the drama?" they cry. "Where's the conflict? Where's the villain and the action and the resolution?" They're so flustered they even have adults speaking in recognizable sentences, with faces visible on screen—something that never happened in earlier Peanuts cartoons, where adults are disembodied ankles and say nothing but, "Wah wah wah wah.”

Peanuts, the comic strip, followed its own neurotic path, with entire Sunday strips based around Charlie Brown getting stage fright when he has to cross the restaurant to pick up a pizza at the counter. Peanuts the marketing phenomenon and multi-media extravaganza was more uneven. Nonetheless, the incompetent creators manage to honor Schulz, if not quite in the way they intended. Bon Voyage, Charlie Brown couldn't be so phenomenally, extraordinarily bad if it weren't ruining something great.