Word of mouth around Kyle Edward Ball’s Skinamarink has been bubbling up for a few months now; like We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, the title became a calling card and a signal of its own, movies that evoked with clarity phenomena and emotions that appear impossible to describe. Unlike We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, Ball’s film is free of any internet influence, damage, or presence at all: Skinamarink takes place in 1995, presumably in Canada, but definitely somewhere cold, blue, and dark. The film runs 108 minutes with credits, many of which run up top, with several amusing additions: “IN COLOR” “SOUND DESIGN…FREESOUND” and a note that the production “followed all COVID-19 protocols,” which struck me as odd, and then the Canadian production company credits came up, and I figured that there’s a similar warning at the back end of most Hollywood movies now, too. Maybe, who knows—at first I compared it to “No animals were harmed in the making of this picture,” but that’s never going away.

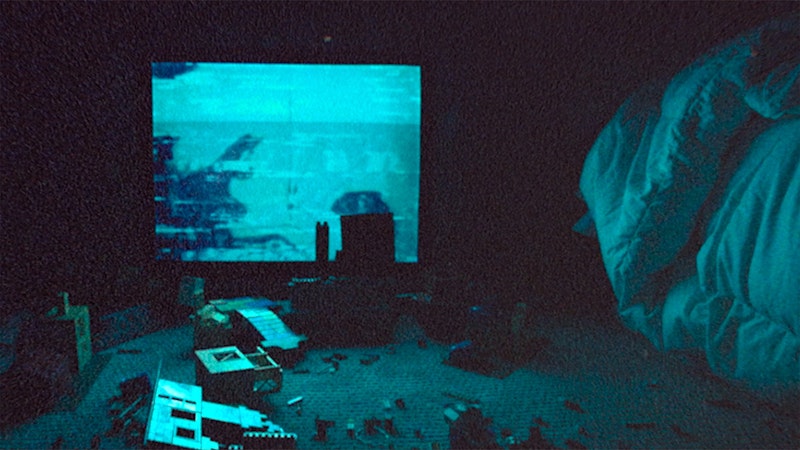

Trailing off into nonsense and no-sleep gibberish is appropriate for a Skinamarink review, a film that’s shot in 2:35:1 widescreen film (presumably 16mm), opens with some very groovy blurred and blown-out piss yellow credits, and consists of relatively long, mostly static shots of a house. We get to know its many hallways, corners, carpets, outlets, furniture, and at least two occupants: two young children, a boy and a girl. They never face the camera, and when one of them does, their face has been smoothed out. All of the compositions in Skinamarink, and the jerky camera moves (when the camera moves), are all at severe angles, usually on the floor, like the two toddlers we see. The camera observes them from a distance like an alien, and as the ambient dread turns into domestic terror, building with some sonic jumps and a subtitled call with a 911 operator and culminating with a pile of blood splattering all over the ceiling. No parents, guardians, or other villains of children are seen, not even demons.

But these kids have been left at home, alone, for a very long time. The subtitle “572 days” comes up towards the end, when one of the kids communes with the other, presumably deeper into her interdimensional monster limbo. The 911 operator isn’t able to save the “brave little guy” who tells him he’s all alone, and that he’s scared. Like We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, which maintained a similar level of ambient dread, the climax isn’t as satisfying or revealing as I would’ve liked. An obvious interpretation of Skinamarink is as the point-of-view or nightmare vision of what it’s like to be a very young child in a house with absent or neglectful parents. The kid calls for his “mommy” many times, including at the end, which doesn’t rule out an abusive household, but Skinamarink shows a world where a child’s worst nightmare is being left home alone and not knowing where their parents are or when they’re coming back. I felt that all throughout my childhood.

Because all of the movie takes place at night, there’s an enormous amount of grain in the film, to the point where practically speaking it becomes animation. Luckily for Ball, artifacts of analog work: his grain is bulbous and chunky, and it looks like maggots are crawling all over that wall-to-wall carpeting. What I found frustrating about Skinamarink is its relatively bold formal structure and its incredibly boring and predictable notes about abuse, trauma, and “real death”—I’ll take M3GAN over patronizing pandering to people who want their horror “elevated.” It’s certainly a better horror film than last year’s Men, and I prefer it to We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, but they’re about even. Pearl is more fun, and like M3GAN, I laughed, had a blast, and genuinely didn’t know what to expect, and that’s the most important difference: you should never be ahead of the movie you’re watching.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith