A cut-and-paste movie is slapped together from the odds and ends of other films. Source materials for these films include the footage of movies never released due to bad test marketing, because their financial backers ran out of money, or creative conflicts halted production unexpectedly. Public domain footage is also ubiquitous. These movies are rarely more than lurid highlight reels for “passion projects” and other oddities that lacked the strength to hang together on their own. A handful of cut-and-paste films have gained cult status, including Ed Wood’s 1953 Glen Or Glenda?, the baffling H.G. Lewis/Bill Rebane collaboration Monster A-Go-Go (which got a popular lampoon via hit TV series Mystery Science Theater 3000), and the artsy crime thriller Targets, an early Bogdanovich film that was part of a series of late-1960s cut-and-paste Boris Karloff vehicles.

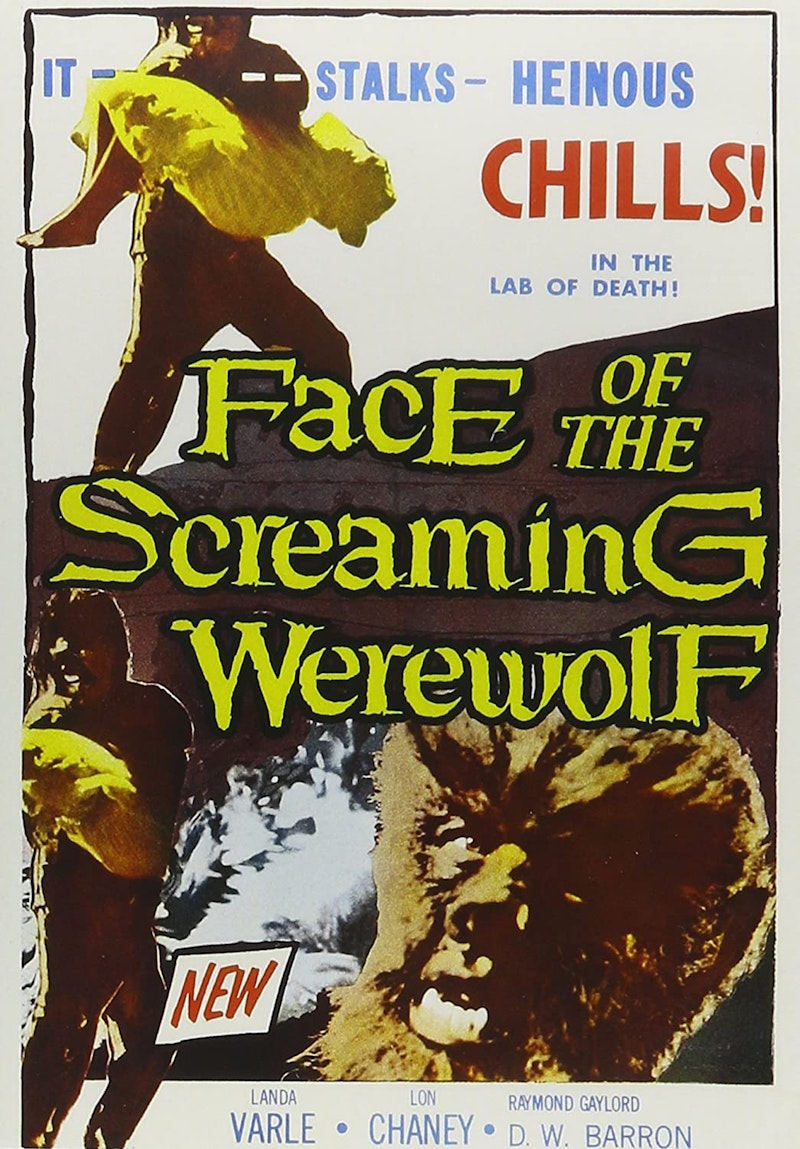

Jerry Warren’s 1964 quickie Face Of The Screaming Werewolf is another great cut-and-paste movie. It focuses on the mysterious connection between a group of archaeologists and a hypnotist’s subject (a reincarnated Aztec princess) who leads them into a secret chamber inside of an ancient pyramid complex. The academics and a crew of laborers steal two mummies and take them to a university for studies and experiments. The amoral scientists bring both mummies back from the dead with electro-shock treatments created by an insane contraption that looks like a Willy Wonka-inspired pinball machine on steroids. One mummy is an Aztec royal in love with the reincarnated princess. The other’s a mummified werewolf portrayed by Hollywood’s most iconic Wolf Man: Lon Chaney, Jr. Why this hairy beast was mummified and interred with the Aztec mummy is never explained.

By the 1960s, Lon Chaney Jr. was mainly cast in grizzled character roles due to the bloated facial features he developed as alcoholism and age took their toll on the once macho square-jawed star. Horror auteurs still beckoned and that disheveled, world-weary appearance only enhances his disturbing performance in Face. Chaney feasts on scenery, owning this film with an electric wordless mania that finds him bouncing off the walls in fits of animalistic bloodlust and fearful confusion while enduring the dream-like transformation effects of make-up artist Jorge Benavides. This is some of the best work that the veteran actor ever did, which is saying a lot considering that his career encompassed a massive resume of films made from the silent era to 1971.

The Aztec mummy doesn’t have the typical head-to-toe bandaging associated with ancient burial customs. This undead freak looks more like a decaying neanderthal with long scraggly hair and shredded clothing. His face is obviously a rubber mask; two empty black holes peer out from where eyes should be. Their cold lifeless non-glare generates unnerving surrealism.

It looks like everyone who even touched this picture had some crazy idea that just had to be fleshed out regardless of whether or not it was relevant to continuity. That enthusiasm, coupled with a lightning pace, makes it much more than just a b-movie curio.

Face Of The Screaming Werewolf incorporates footage from three different sources, including two films made in Mexico that were never officially released in the U.S.: the Lon Chaney, Jr. werewolf flick La Casa del Terror (1960, directed by Gilberto Martinez Solares), La Momia Azteca (1957, directed by Rafael Portillo), and exclusive U.S. footage created by Jerry Warren in 1964. Warren plotted and edited all of the disparate strands together, some of which have a rich textured graininess that makes them look similar to early video tape productions. The varying qualities of film stock add to the dream-like atmosphere of the movie with actors often appearing to interact while existing in two different dimensions.

Though the story’s disjointed, a running theme unites the mummies’ brutal rampage: each monster is extremely unhappy. The werewolf mummy is possessed by self-hatred; Chaney’s terrifying outbursts constantly remind the viewer that his character never wanted to be a werewolf. The Aztec mummy’s unrequited love for the reincarnated princess is the only thing that keeps him going. He obsesses over a hallucination of the princess’ face and memories of her unexplained involvement in his ritual death, a tense moment re-enacted in a highly stylized musical sequence near the film’s opening that sets the tone for all of the action-packed insanity that follows.

Even the movie’s title makes a bold statement with its graphic description of a monster’s frazzled emotional state. It’s rare that a horror film can be so emotionally powerful while side-stepping narrative conventions. Like many of its cut-and-paste counterparts, Face Of The Screaming Werewolf’s power comes from the inventive ways in which it uses modest source material to create haunting drama and unforgettable imagery.