Warren Beatty shouldn’t have punted. If the envelope holds the wrong card, don’t show the envelope to Faye Dunaway and expect her to straighten things out. She hasn’t before, she won’t now. Beatty’s choice may never be explained. He left the matter blank when he leaned toward the audience and reminisced about the recent disaster. “I wasn’t trying to be funny,” he said. What had he been trying instead? He didn’t say. He’d certainly looked like he wanted to be funny when he’d been hiking up his eyebrows and making a triangle of his mouth. He looked down at the envelope, swiveled his head toward Dunaway, then looked at the envelope again.

He’d already been drawing out the suspense, pausing from one word block to the next: “… and the Academy Award… for best picture…” Then came the fateful moment. “You’re awful,” said Dunaway, giggling, and she looked down at the card that he had pushed into her airspace. “La La Land,” she said with the intonation of one who caps some horseplay by cheerfully cutting to the chase. She didn’t notice Emma Stone’s name or anything about best actress. Beatty had, but his response was to get the matter off his hands. Odd, since he’s one of the few stars to also make a career as a director, screenwriter, and producer. Behind the scenes he’s always been Mr. Slick and has gathered control into his own hands, a trait shown by his detail-conscious productions and bloodless, gimmick-heavy scripts. The luscious Joan Collins had a similar tale to tell, looking back on her affair with the beautiful boy of half a century ago. “Warren could handle women as smoothly as operating an elevator,” she or her ghost writer recalled. “He knew exactly where to locate the top button. One flick and we were on the way.”

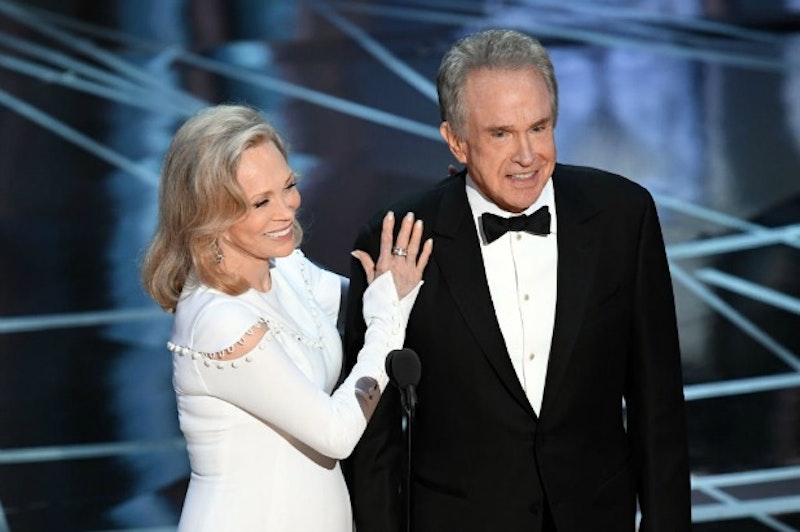

The man who did that shouldn’t be flummoxed by the wrong card. Beatty’s now 79, and Dunaway 76, but their manner seemed sharp enough. They appear to have been outfitted with the sort of high-quality, glossy old age that comes with advanced science and decades of money. Bones and ligaments would seem properly firm and buoyant. The stars’ faces have been incised more deeply, but everything from chin to eyes has stayed in place instead of slipping down; above the eyes things may have moved higher. Dunaway in profile suggests that plastic surgery has grown insidious in its power: one moment, with her hair pulled back, there’s a suggestion of a monkey’s skull, but the next all the features line up as they should and she’s beautiful. Beatty has two frosty smears of icing for eyebrows and then a corrugated expanse of forehead topped by his hair, a ridge made of more frosting. You can’t be young and look that way. On the other hand, it doesn’t seem a bad way to look.

Beatty does seem smaller than before, but that brings him down to normal. He’d always seemed out of proportion, like a mountain face or rock formation that had somehow wound up as a good-looking guy. The senior citizen Beatty is no bigger than the producers of La La Land, who milled on stage with him and Dunaway as the truth dawned about which picture was really getting the Oscar. One of those producers, Jason Horowitz, has been faulted by some on Twitter because he snatched the Best Picture card from Beatty’s hands and held it to the camera, wanting to establish once and for all that the true winner was Moonlight. How Beatty felt is hard to say. He appeared sheepish but not really cast down, but that’s how he played most of his roles. The oversized hunk of beautifulness had often found canny ways to play against his physical glory, making himself come off as passive and even bumbling while still taking center stage as his due. (Example: in Bugsy he’s bobbling between the birthday cake he has to make in the kitchen and the mobsters he has to appease in the living room, and all the while this large man is wearing a white chef’s hat that’s tall as a wind sock and hanging down the side of his head.)

Now the former giant has shrunk and center stage is no longer his. The powerhouse producer, or former powerhouse producer, had to stand by while the action-oriented Horowitz took charge. As Mr. Slick, Beatty had used his clout to create some classics (Bonnie and Clyde, Shampoo) but also a series of tightly controlled, clever, expensive duds (Reds, Dick Tracy, Bugsy and the top-notch but financially disastrous Ishtar). Last night Mr. Slick gave his career the footnote most people will remember him by, and it’s as the amiable goof he so often played.

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3