The Dark Knight Rises is not just a movie—it’s a cultural event. You don’t just see TDKR—you see it at midnight along and you wear a costume, dressing up as your favorite character, bringing the movie into real life. I thought about seeing TDKR later today or this weekend, but I figured that going to the midnight screening was actually a large part of the movie itself. I know I couldn’t wait to see it the second I heard they were filming, and apparently I wasn’t the only one. Tickets for TDKR were available as early as January and began selling out in some theaters immediately. For months the finale to Christopher Nolan’s Batman triptych teased rabid fans with trailer after trailer, teaser after teaser, rumor after rumor.

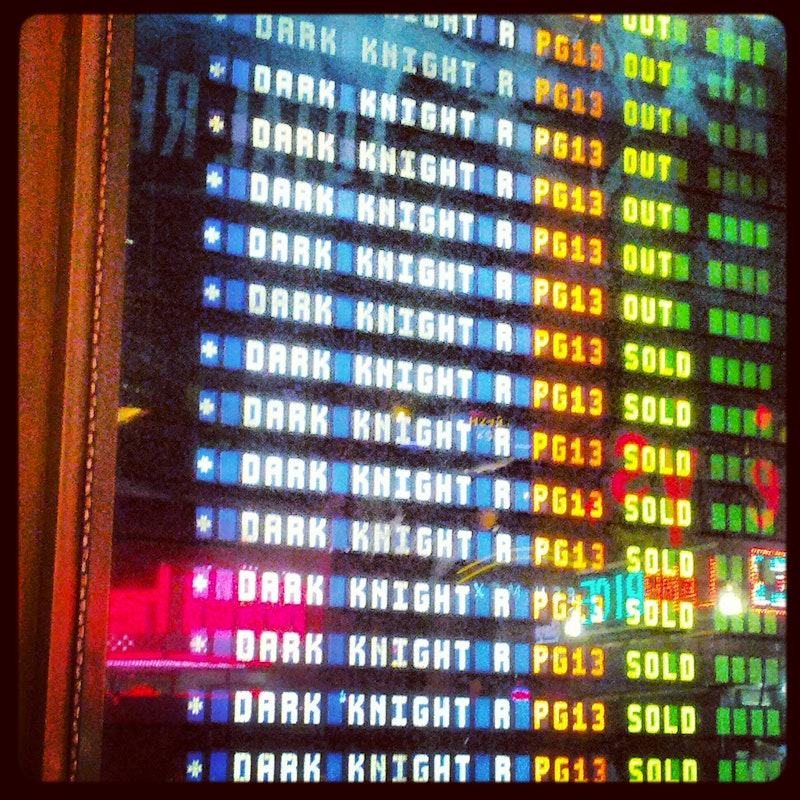

There are more than a dozen movie theaters in New York, all of them with big, multiple screens, and the whole thing was sold out. Show times were 12:01, 12:03, 12:04, 12:05 and on and on—all the way up to three a.m.! I saw TDKR at the AMC 25 in Times Square, a place I typically avoid, and the theater handed over all of its 25 screens to Batman and the nearly inaudible Bane. I have to say, though, that I wonder how much being “sold out” was part of the marketing, because in the theater where I saw the movie, there were still several seats left in the way front, so it wasn’t sold out sold out.

Audience members wore Batman t-shirts, capes, and more than one girl came in a leather onesie like Catwoman. I don’t know why I didn’t think to do that. When I left the theater, droopy-eyed at three in the morning, there was a huge line of wide-awake fans and fanatics waiting for the 3:25 a.m. showing, all ready for some good Batman fun. I walked 30 blocks south to my subway station and along the way I passed herds of Catwomen and people in capes who were just coming from their own screening of TDKR. I’d never seen anything quite like this, such rabid fervor for a single movie all over the city. It was all part of the experience.

This rabid fan base, however, comes with a price. When I saw the tragic headlines this morning that a man wearing a gas mask opened fire at a midnight screening of TDKR in Colorado, killing 14 and injuring 38, I immediately thought he was a terrorist trying to bridge the gap between the dystopia and anarchism of the movie and real life. The Batman movies are about how a relentless terrorist can unleash havoc on the supposed order of social life, setting the people free once and for all, and part of their appeal is that audiences believe that this scale of urban violence is impossible. No oversized man wearing a mask that pumps him full of painkillers is really going to take over cities. News reports show that the gunman, who was playing the unscripted role of real-life villain, wore a bulletproof vest and did not resist the police upon his arrest. He threw a gas canister into the theater and opened fire on the audience 20 minutes into the movie, and apparently the gunman’s apartment was “booby trapped.”

It sickens me that people going out to catch the highly anticipated and much-hyped Batman finale got caught up in a real-life terrorist’s video game. Where does the hate come from? How can one person harness the will for so much violence? Do we need better gun control? What effect do violent movies have on terror plots? Maybe it’s good that this is the end of Nolan’s Batman, because the movies always seem shrouded in real life tragedy.

Violent Thrill Rides and Real Life Tragedy

A shooting at a midnight screening of the new Batman movie leaves 12 dead.