This article is part of an ongoing series. Read part one here.

When does bad become sublime? The answer varies from movie to movie. For insurance/fertilizer salesman Harold P. Warren, it probably happened around the time he decided to retitle his movie Manos: The Hands of Fate, which translates to Hands: The Hands of Fate. Legend has it that Warren bet screenwriter Stirling Silliphant (In the Heat of the Night, The Village of the Damned) that he could make a horror movie, and the result is possibly the most shoddily-assembled feature film ever produced, almost impressive in its lack of coherence and technical competence.

Beneath Warren’s crude approach to filmmaking—the out-of-focus shots, non-existent lighting, ridiculous performances, slapdash ADR (with several parts overdubbed by Warren), glacial pacing and choppy editing, among the many other evident deficiencies that make Manos the movie it is—exists something resembling a normal horror movie. One of the many funny things about Manos is the gap between its intent and execution. Take the opening shots: first, a slow pan over El Paso from a lookout point, likely meant to be some sort of establishing shot but way too primitive for that to be clear; then, a handheld shot of a different hillside view overlooking El Paso, as if Warren initially decided against the pan and, once in the editing room, just decided to use both. As if each was so good, it was impossible to choose between them.

After this, the movie introduces its main characters: Michael (Warren), his wife Margaret (Diane Adelson), their daughter Debbie (Jackie Neyman), and Debbie’s adorable little dog Pepe. We first see them driving in a convertible. They’re supposed to be on vacation but have gotten themselves lost. Debbie’s hungry, and it’s cold outside. Michael insists they aren’t lost and the road they need is just a few kilometers away. Before long, a cop pulls them over for a broken tail light. Michael talks his way out of a ticket, but the officer tells him to fix the light as quickly as possible.

From just a plot synopsis, Warren’s intent is pretty clear: the cold weather, Debbie’s hunger, and the tail light all force the family to either reach their destination or find someplace else to spend the night. But none of that is apparent in the film, especially when the intro is followed by over a minute of footage shot from a moving car, a credit sequence without the credits. It’s unclear if Warren forgot the credits or couldn’t afford to add them; in any case, this nausea-inducing montage (set to atrocious lounge music) is the ideal way to kick off such a weird and deeply confusing little piece of unicorn cinema.

Smash cut (with completely different music) to two teens making out in a convertible. They see Michael’s car pass and wonder out loud where he might be going, since the road they’re on leads nowhere. As far as I can tell, conveying this bit of information is the only purpose these characters serve (though the film continually, inexplicably returns to their makeout sessions). When the police officer from earlier breaks up their party, we get a hilarious shot that perfectly encapsulates Warren’s one-take, no reshoots ethos: the actress, seemingly unaware that the camera is rolling, primps her hair in the mirror; after a second or two, she turns to the camera and, with what little authenticity she can muster, pleads, “Why don’t you leave us alone?”

After nine minutes of extremely clumsy exposition (in which Michael refuses to ask for directions about four separate times), the family finally arrives at the film’s main setting: a lodge in the middle of nowhere, overseen by the bearded, vaguely bestial Torgo (John Reynolds). There’s something immediately off about Torgo, a bundle of micro-contortions in the shape of a 1930s hobo. If I had to compare Reynolds’ performance to anything, it would probably be a malfunctioning cartoon robot that’s just about to explode. “I’m Torgo,” he says. “I watch the place while the Master is away.” Torgo offers no help in getting Michael and his family to their destination. “There is no way out of here,” he says rather cryptically. Michael sees nothing weird about any of this, and decides—against his wife’s wishes—that they’ll just stay there for the night.

None of the attempts at horror in Manos work, but the movie does achieve a completely different kind of unintentional horror. In the film’s classic episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000, Joel Hodgson remarks, “Every frame of this movie looks like someone’s last known photograph.” It’s true: the film’s frequently out-of-focus 16mm compositions lend the film a faded photograph quality that’s creepy. The desert town setting looks like a terrible place to get stranded, one of countless isolated dead ends in the most remote corners of America. As Manos progresses, it feels increasingly like a fever dream in which not much happens but is nevertheless filled with unease and dread. That feeling is heightened by the insane behavior of the movie’s protagonist, whose dismissiveness of Margaret borders on gaslighting (“Don’t worry about it, it’s just your imagination”).

Back to Torgo: apart from his stilted delivery and bizarre mannerisms, the thighs of his pants are also padded with what appear to be pillows. Combined with a bowlegged walk, this costume innovation is meant to make Torgo look like a half-animal of some kind, but like everything else in Manos, the execution falls short of the intentions. Despite his warnings that the “Master will not approve” of Debbie and Pepe, Torgo agrees to bring the family’s luggage inside for the night’s stay, his outrageous walk retarding the film’s already sedate pace. In fact, if you cut every part of Manos that consists of Torgo walking or Michael and Margaret standing around silently while Torgo’s “theme” plays (really just a few seconds of music looped over and over), it would probably be about 30 minutes long. Warren pads as much as possible to get his feature length running time, resulting in a film that’s only 69 minutes but feels twice that long.

When Pepe runs away, Michael finally decides it’s time to leave, but the car won’t start. Debbie runs off to find her dog, but returns with another dog that closely resembles one depicted with the Master in an oil painting at the lodge. Meanwhile, Torgo practices his game on Margaret, cornering her in the bedroom and making a very awkward pass. Torgo’s expressions during this scene remind me of the faces Martin Short conjures in Clifford when Charles Grodin commands him to look at him “like a human boy.” It’s a performance that reads like an alien’s pathetic attempt at mimicking human behavior. (Add Vincent D’Onofrio in Men in Black to the list of reasonable Torgo comparisons.)

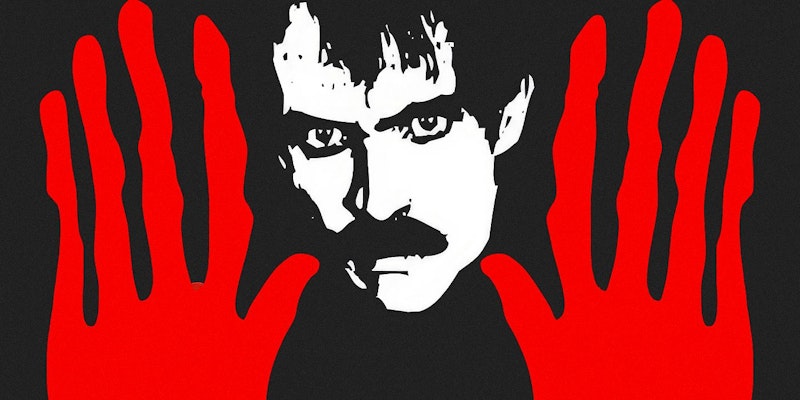

Manos takes almost a half-hour to finally get to the Master (Tom Neyman), a Frank Zappa lookalike draped in a black cape that’s stitched to his arm sleeves; whenever he raises his arms, which is pretty often, the inner cape reveals two large red hands. The Master lives with a harem of wives in white dresses who sleep standing upright against large pillars. I think this is meant to be the final circle of hell where the Devil and his slaves live, but given how poorly lit the nighttime exteriors are, it’s difficult to be sure of exactly what’s happening. It feels more like a hippie commune that’s seen better days, but that might just be the strong acid casualty vibes coming from Torgo. Not having learned his lesson after Margaret, he fondles the Master’s wives while they sleep and delivers a monologue that sounds like a proto-incel manifesto.

The remainder of the movie is taken up largely by scenes of the wives wrestling over whether or not to make young Debbie one of the Master’s new wives. For the crime of lecherous horniness, they sacrifice Torgo to Manos (it’s never clear who or what Manos is), a death by smothering—or something like that, it’s pretty confusing. Torgo may have crossed a line, but it seems hypocritical for the Master to be angry with him while he openly debates whether or not to marry a child.

Once they finally decide that they will enslave Margaret and Debbie, with the lone dissenting wife burned at the stake for her insubordination, the remaining wives go out in search of the family. The officers from earlier hear gunfire in the distance—Michael shooting at a rattlesnake—but reckon that it’s so far, it could have come all the way from Mexico City (a roughly 1800 kilometer distance). Eventually, it’s daytime again, and two women travel down the same lonely dirt road, arriving at the lodge. Michael’s at the door to greet them, the new Torgo. Debbie and Margaret have assumed their new roles, standing in white gowns at their pillars. The end.

What is there to learn from Manos: The Hands of Fate? Perhaps the lesson is that making a movie is more difficult than it seems. Almost no one who worked on the film went on to do any other movies. (The one notable exception is prop painter Stephane Goulet, who would serve as prop designer on Michael Snow’s avant-garde masterpiece Wavelength the following year, the rare crew member who can say they worked on one of the worst films ever made and one of the best films ever made within a year of each other.) But as bad as Manos is, I would never want to reduce it to its shortcomings in quality. Like all the most audacious amateur forays into vanity project filmmaking, Manos offers a peephole into its maker’s mind. Shot in the mid-1960s, when Warren was already middle-aged, the movie depicts the era’s changing sexual mores from the vantage of the “Greatest Generation,” a radical shift that repels and tempts a square like Warren in equal turns. That ambivalence defines both Manos and its director, who explores his prurient interests and desires almost exclusively via patriarchal avatars of father, Master, and cockblocking police officer.

Warren set out to make a horror flick, and with its snuff movie aesthetic and desert doom bad vibes, Manos doesn’t entirely fail to deliver. If nothing else, it’s a mess of poor filmmaking technique, a movie that tops every bad decision it makes until, like Sander in Uncut Gems, you can’t help but root for it. The bad becomes sublime. That’s the power of Manos, the mighty grip of the Hands of Fate.