When the Criterion Channel streamed a collection of 1970s science-fiction films in January, they organized the movies by year of release. The last film in the collection was a 1979 production that anticipated the 1980s as much as it looked back to the other movies. Its post-apocalyptic setting would’ve been familiar to 1970s audiences, but the gliding camera moves feel more like the Spielberg decade to come. Still, what’s most surprising about the film is how different it is from its sequels.

George Miller’s Mad Max was originally conceived as an action movie set in the present day. Written by Miller with James McCausland from a story Miller created with producer Byron Kennedy, Miller found as he worked on it that the intensity and violence were easier to believe if he set it in the future, causing the story to take on “a more fable-type quality.” An opening title card tells us that the movie takes place “a few years from now,” but there’s not much on the surface about the world beyond that. Which opens the film up for some interesting readings.

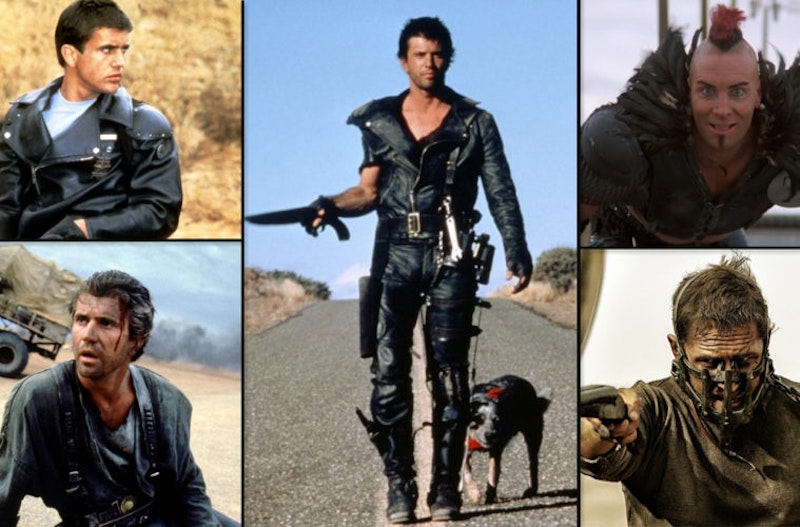

It’s a story about a highway cop, Max Rockatansky (the young Mel Gibson), part of a police force somewhere in Australia doing battle with an outlaw biker gang. The cops arrest one of the bikers for rape, but witnesses are intimidated into silence, so the justice system tosses the case. The bikers retaliate against one of Max’s cop buddies, after which a depressed Max takes a vacation with his family. But following another clash with the bikers, Max goes over the edge and sets out for final vengeance.

It’s an entertaining, fast-moving story with effective car chases, a respectable amount of violence, and humor that mostly works. You could make an argument about the film being a moment in which 1970s grittiness is given 1980s gloss, brutality made more show-biz, but that might be reading the film through the lens of its sequels. In fact, the film’s in no hurry to get to the revenge angle, spending most of its time showing Max within a kind of community context before he becomes an obsessed loner.

It’s not exactly accurate to say that the film’s interested in character relationships, not in any depth. But cops and bikers are both individualized. The bikers in particular have distinct looks and attitudes, setting them up as specific antagonists. Max’s boss (Jonathan Hardy) and his best friend (Steve Bisley) have coherent personalities. His wife Jessie (Joanne Samuel) isn’t particularly individualized, but shows competence and strength of will.

As an action movie, the reason the film builds up the characters is to set up the action. Max inevitably emerges as the center of the story, the best cop on the force. The revenge-movie beats may be slow to come, but in due course emerge. They’re well-executed, with chase scenes and automotive carnage beyond what you might expect of a low-budget film.

But what makes the movie stand out is its setting. Because the story wasn’t developed as post-apocalypse fiction, its post-apocalypse world is original and credible. Specifically, institutions still function. Existence isn’t centered around subsistence-level survival. Nobody’s conceding that they live after the end of civilization.

The idea of this future is that the world’s running out of oil—the most overtly science-fictional scene sees some bikers hijack a fuel truck. This means that instead of war or plague bringing an abrupt end to the world as we know it, we’re watching a slow running-down of things. Characters are still raising kids and going on as normal. They still think there’s a future to be had. This is the only post-apocalypse story I know of in which somebody’s boss tells them to go take a vacation.

The structures of the world haven’t fallen apart. A hospital still runs, with functioning medical technology. An organized police force functions, even if the headquarters is crumbling. There’s a court system that sleazy lawyers expect will still rein in the police.

But here’s where things go off the rails. Because once the lawyers get the bikers off, the bikers attack Max Rockatansky’s family, leading him to quit the force and hunt them down. In other words: the decaying system can’t stop the bad guys, so Rockatansky has to leave the system to get justice—and the system can’t stop him from doing that, either.

We’re watching society break down. Mad Max has a standard revenge-movie plot, but by putting it in the future it emphasizes something maybe always implicit in the genre: this can only happen when societal institutions are in decline. The law can’t stop the bad guys, so the hero has to take the law into his own hands. And, in this movie, there’s no worry about him getting away with it. Max going mad has no repercussions. It even makes sense. Everything’s going to hell. Why bother staying a cop?

One of Max’s superiors tells him, early on in the movie, “People don’t believe in heroes anymore.” Max can be the hero the people need, is the point, a theme revisited in a monologue Max has about his father. But that kind of lone-wolf hero can’t be part of an institution. Individual heroes are what you get when institutions don’t do the job as a matter of course—and by existing they usually lead to the institutions rotting further. Make a hero like that, and the world collapses further.

In the end Rockatansky the road warrior takes down the baddies, but the cops are left weakened—many of them dead, their best man off the force, their civilization unable to deal with the rising tide of anarchy. Max wanders off into the wasteland at the end of the film, but you have to think all his world’s going to turn into wasteland, sooner or later. Which, in retrospect, is a fairly accurate take on the 1980s.