The War Room was the last movie I rented from Video Americain’s Charles Village location. It was December 2011, and I’d just moved into an apartment one block down on St. Paul St. After getting everything upstairs and ordering a pizza from Maxie’s downstairs, I went and got The War Room. I was obsessed with the election cycle that year, along with news of the Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street and Libya invasion. I still have no idea why I largely tuned out what was going on around me that year—things were still relatively active and promising in the Baltimore art and music community—in favor of staying home and watching the news. This would’ve made a lot more sense a few years later, or a few years before, but 2011 and 2012? I really still don’t understand it. Maybe because it was such a boring election, the only real content of that cycle was the structure and the tropes of contemporary campaigning, politicking, and the thin veil between reporters and spokespeople.

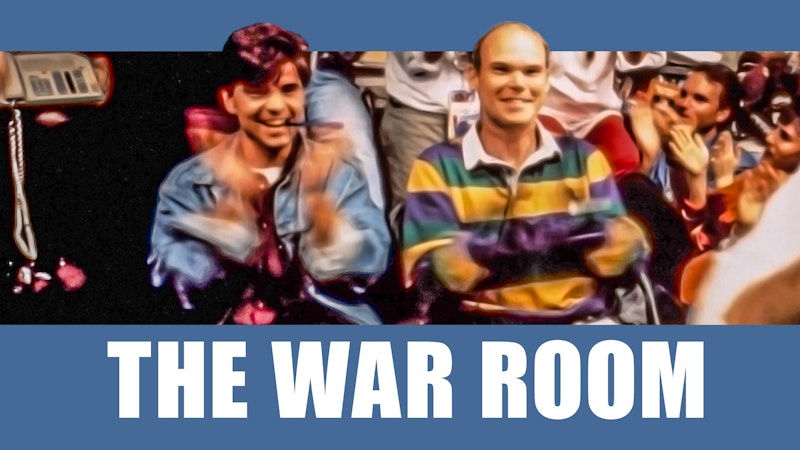

Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary struck me as on par with the latter’s masterpiece Dont Look Back, if only for the crew’s incredible luck in following a successful presidential candidate from the first primaries in January all the way through to the election in November. James Carville and George Stephanopoulos were still stars in 2011, and they’re still around today, entrenched in the political pop cultural firmament. Near the end of The War Room, a choked up Carville can barely get through his thank you speech to his crew in the titular “war room”: “I was 42 years old before I won my first campaign… you’ve all done a beautiful thing. I’ll never forget it.” Today, it feels like Hegedus and Pennebaker linger on Carville’s self-congratulatory speech a bit too long, leaving in long stretches of choked up, whimpering pauses. It’s all a bit rich now, but it was, embarrassingly, somewhat moving over a decade ago.

There’s no difference in the construction and performance of Carville as the hero of this movie and Donald Trump’s own construction and performance as President of the United States over the last decade. Carville and Trump are far more alike than the former would like to acknowledge; along with Stephanopoulos and their boss, Bill Clinton, Carville continued to blur the lines between celebrity and public servant, a shift that began as soon as John F. Kennedy won a debate on television and lost on the radio in 1960; Ronald Reagan would arrive in 1980 as the culmination of Hollywood, an enigma who could do or be anything and make everyone feel safe, knowing this was all too stupid to go wrong.

There’s nothing in The War Room that distinguishes Democratic operatives, many of whom are still working today, from their contemporary rivals and the specter of Trump. When Mickey Kantor comes in and says, about the entire state of Indiana, “These people are shit,” Carville and Stephanopoulos say nothing and start slowly moving away from the camera—they don’t want Kantor fucking up their star vehicle! This is on election night, and they know if Clinton wins, they’ll be in an even better position because of the documentary crew. Their media careers were locked before they ever accepted and performed their duties in the White House. The War Room is the reason both Stephanopoulos and Carville are still on television. Like Trump and The Apprentice, this was what they really wanted all along: fame. Not power, necessarily, but fame. It’s that fickle and frivolous drive that will make fools out of whoever loses, and semi-divine geniuses of the winners.

In Hegedus and Pennebaker’s 2008 retrospective Return of the War Room, Stephanopoulos expands on the campaign’s strategy following an early challenge: Gennifer Flowers. “Remember that this is a man who was raised in Arkansas by a single mother… when you start to put the pieces of his life together, it’s not so strange.” Paul Begala adds, “Gennifer Flowers was one star in the sky. But we could add other things: supported civil rights at a young age, roots in Arkansas, single mother… to sort of add to the constellation.” Their pride in their cynical media manipulation is only 16 years old, and of course they’ve all gone further and further off the cliff, driven off either by insanity or irrelevance in the age of Trump.

Carville shouldn’t be surprised by Trump’s surge in popularity. Privately, he probably isn’t. He can’t be. Unctuous beyond belief, The War Room is still essential documentary cinema, a testament to Pennebaker’s abilities as a cameraman and editor. Now, he’s dead. Why can’t there be a filmmaker one one-thousandth his talent inside the Trump campaign, or the Harris campaign? It must be juicer than ever. Maybe next election cycle, when we could have our first mumblecore candidates, men and women raised on Arcade Fire and flip phones. This isn’t the end…

—Follow Nicky Otis Smith on Twitter and Instagram: @nickyotissmith