“The greatest danger of all is when someone, or something, controls your mind,” Wildboy explains sincerely at the tail end of Sid & Marty Krofft’s Saturday Morning Hits. He is translating for his semi-articulate friend/foster-parent Bigfoot, who, when Wildboy is done, shakes his shaggy head in agreement and declaims, “Ugh!”

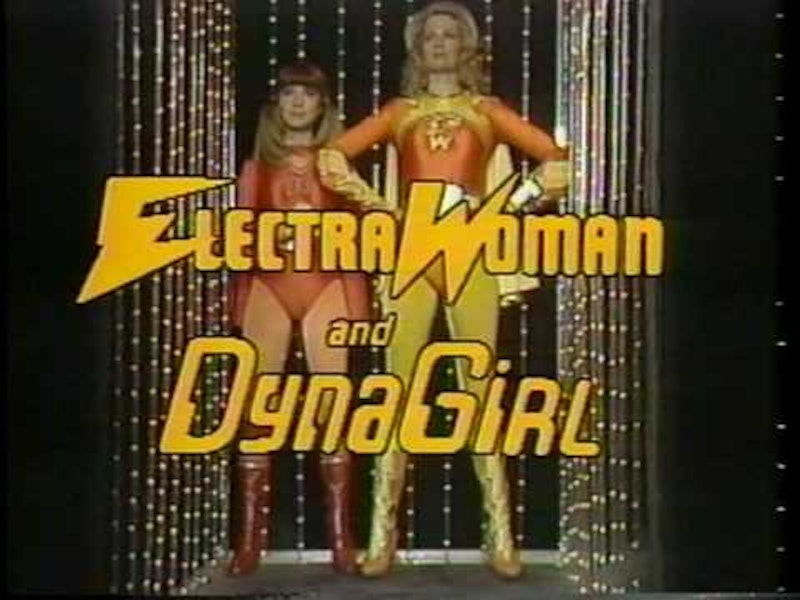

Profound words indeed—and you can’t really understand how profound until you’ve seen every episode in this two-and-a-half hour anthology of the Kroft’s numerous psychedelic 70s life-action shows. In the aforementioned "Bigfoot and Wildboy" episode, a professor is turned into a (very low-key) zombie-like slave by a couple of ominous figures in Jawa hoods whose touch melts rock. In one of the two "Wonderbug" episodes, the friendly supercar Wonderbug is hypnotized (“your motor is getting sleepy”) and turned into a bank robbing supercar. In "Electra Woman and Dyna Girl," super-heroine Dyna Girl is sprayed with a mist that turns her as evil as she was good, prompting actress Judy Strangis to indulge in some of the most disturbing overacting I’ve ever witnessed. She opens her mouth to display her aggressively perfect teeth and rolls her eyes this way and that until, with her cute pigtails, she looks like a Barbie doll possessed by Belial. Even the monumentally hammy Sid Haig, playing a supporting villain, is definitively out-mugged.

This isn’t to suggest that the only plot device on offer here is mind-control. Not at all. There’s also body-swapping, as when the evil magician Horatio J. HooDoo turns himself into an exact duplicate of plucky hero Mark in order to fool the Good Hats and climb the beanstalk out of the magical land of Lidsville. And there’s voice-swapping, as in the episode "The Bugaloos" where the nefarious Benita Bizarre manages to exchange her hideous cackle for the dulcet tones of singer and butterfly Joy. And, when all else fails, there’s always dress-up—dinosaurs masquerading as guards; insects masquerading as electricians; teenaged geeks masquerading as Colombo; witches masquerading as oranges.

That witch, is, incidentally, Wilhemina W. Witchiepoo (Billie Hays), and she dresses as a citrus fruit in order to steal a magic talking flute named Freddy. The most intense emotional moment of the episode is probably when Witchiepoo gets the flute, holds it close to her pointy nose, and demands that it sing for her: “Now, my little gold darling, play for me!” It’s an insinuating come-on made directly to a talking phallic symbol. Later, at the very end of the episode, Witchiepoo tries to zap the good guys with her wand…but, alas, the wand has gotten wet, and it droops impotently in her hand.

Polymorphous perversion has been a central part of children’s lit since Alice ate something she shouldn’t have and had her neck grow to such proportions that she was mistaken for a snake by the local fauna. Dominance, submission, mind control, role-playing, limp phallic symbols and close relationships between two loving hairy men—is it all innocent fairy tale or flamboyant camp naughtiness?

For adult viewers, at least, much of the pleasure is that it’s both. You can wonder at a landscape in which the trees and rocks literally sit up and talk—the inventiveness of the puppets and the surreal nuttiness of the storytelling. And at the same time you can smirk at Sparky the firefly, whose rear end lights up when he flirts with Joy in the Bugaloos. You get the pleasure of innocence as well as the pleasure of knowing something you’re not supposed to know.

Perhaps my favorite moments, though, are the ones where child and adult registers bump against each other, producing a sense of the uncanny. Dyna girl’s demented laugh is like that. So are the opening credits of Sigmund and the Sea Monsters. Two middle-school aged kids run through the surf and play volleyball with Sigmund, an adorable green, Cthulhu-like critter. There’s something eerie about the matter-of-fact incongruity of it. It reminds me of the cover of Led Zeppelin’s Presence, with the ominous black whatever placed with brazen mundanity in various Norman Rockwell settings. Sigmund, in all his bouncy, snaggle-toothed adorableness, is a Thing That Shouldn’t Be There. In the boy’s sun-dappled existence, he’s the plush polymorphous shadow. His very wrongness makes their happy, healthy rightness seem over-ripe.

For the Kroffts, childhood is often a suffocating sweetness, a threatening plenitude. In both H.R. Pufnstuf and Lidsville, a boy is trapped in a magical realm from which he spends almost all his time trying (and failing) to escape. The child’s plight is especially unsettling in Lidsville, where the boy in question isn’t really a child. Butch Patrick, who played the protagonist Mark, was 18 when he picked up the role and close to 20 by the time he finished. When he wanders through the magic world of sentient hats, tyrannical patriarchal magicians, and evil doppelgangers, therefore, it doesn’t come across as a child’s adorable game of make-believe. Instead, it looks disturbingly like a young man’s schizophrenic fugue.

In fact, the Kroft’s world is one in which everyone seems brain-damaged—stuttering out banal jokes with a fixed stare, twitching their faces frantically, running in slow motion through the great, vast emptiness that separates plot point from plot point while cheesy funk chase music starts and stop on the soundtrack at random intervals. The clunkiness of the shows—the low-budget, the absurdity, the clanking plots—makes even the characters who aren’t wearing giant cuddly outfits seem like puppets attached to invisible strings. Everyone comes across as children pulled and pushed through nonsensical hoops by unseen authority figures, or as adults staggering through nonsensical hoops at the behest of a dictatorial child atavism. The grown-ups ruthlessly and weirdly shape the minds of the kids, and the kids retaliate by ruthlessly and weirdly shaping the minds of the grown-ups they’re going to be. And that’s the world of Sid and Marty Kroft, where adults are children, children are adults, and everybody seems to have had their brains scooped out with a mellon-baller.