There was a particular pastime in my life that exists largely to construct expectations—and though easily avoidable, I can’t help but entertain them: the reading, or over-reading, of film criticism. Ever since I was a little girl, I made a habit of digging through the unwanted folds of Friday’s New York Times until I reached the “Arts & Leisure” section. From there, I’d pore through the lines of reviews for that week’s releases. It’s a ritual I still carry out today, though am not entirely sure why, seeing as I seldom agree with the critics’ verdicts. A.O Scott tries too hard to be hip (“Sex, drugs, blood, gore. Love it or leave it!”), while Manohla Dargis tries too hard to hate everything. (Often when she does champion something, it is absolutely inscrutable as to why. See last year’s Eastwood mess: Edgar, J.) I still read them, simply because I love film, wish to be informed of the current offerings, and like to procrastinate.

A couple of years ago, however, I discovered something far more satiating, a means by which I could mainline the ingestion of criticism: the film festival circuit. No longer did I have to wait an entire week to read about a few films I probably had little or no desire to see. Now I could read about dozens and dozens of (typically “quality”) films, churned out of screening rooms over the course of a few weeks like sausages at a slaughterhouse. Moreover, these festivals seemed to attract critics who did not simply produce reviews, but rather, literature. (InContention’s Guy Lodge is something of a poet.) And yet, it was only a cycle or so later before I encountered the downside to tracking the festivals’ trajectory. As opposed to having a few days, or hours, to build up one’s expectations, reading festival reviews means you have months and months to construct your preemptive opinions, drawing from a hodgepodge of others’. Even if these takes have ultimately nothing to do with your own, they still manage to thwart and shape your expectations. The reception of this year’s festival darling is a prime example.

The first time I heard of Beasts of the Southern Wild—outside of a few Internet murmurings—was in early February. (I tended not to pay as much heed to Sundance in college as it coincided with my winter break, and big players resurfaced later on in the season.) My boss, however, had just returned from Park City, and was ranting about the “blow your mind good” film from a young director he’d been “tracking for a few years now.” Perusing a few articles at my desk, I noted he wasn’t exactly a solitary plaudit. The Hollywood Reporter claimed it was the best film to premiere at Sundance in decades. (It won the Grand Jury Prize and Achievement in Cinematography at the festival.) Described as a deep-fried Bayou tale of familial relations, natural tragedy, and magical realism, with a touch of Terrence Malick, my excitement started to build. The buzz grew in May, when it won the Camera d’Or for Best First Feature at Cannes. And just a month later, it hit theaters in late June, to even further, thunderous critical applause. Without ever intending to do so, the strain of my curiosity and excitement built to insurmountable expectations by the time I took my place at New York’s Sunshine theater.

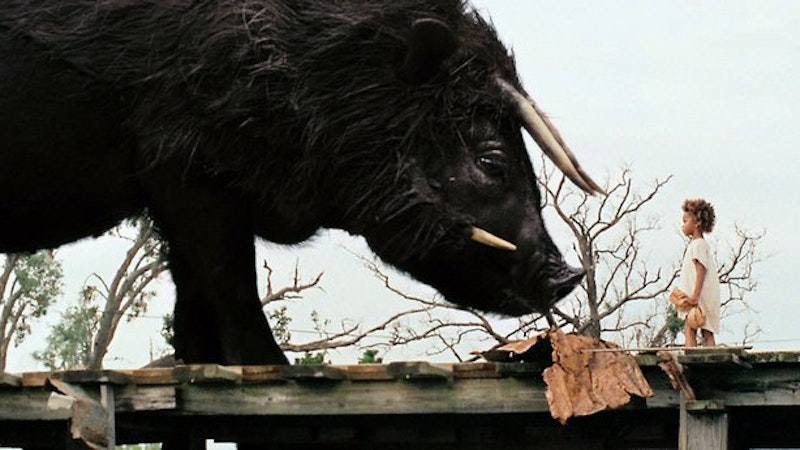

The film was stunning, the performances were amazing—especially given the inexperienced cast, culled from local schools, bakeries, and the like—but the story, or rather the storytelling, was lacking. Benh Zeitlin, the director and co-writer, interestingly enough, is the son of folklorists. It shows in parts, as all of the traditional elements are there—interconnected metaphors and magical realism abound—but when Zeitlin moves beyond the souped-up haven of “The Bathtub,” the story arc begins to splinter, and subsequently falter. He is so comfortable exploring the niche he’s created that he neglects cohesion. The push-pull between the sprightly protagonist Hushpuppy and her booze-addled father, Wink, becomes almost routine, no matter how much it tugs at your heartstrings. Upon entering the outside world of a hospital/holding compound in the second and third acts, Zeitlin appears almost as out of his element as his characters feel. Beyond the wavering, meandering camera is a desire to confront a more traditional narrative that is not quite realized. But what of it?

As I walked out of the theater, I went straight to nit-picking its faults, even though it was quite wonderful. At first blush, I neglected the fact that I was brushing the tears off my cheeks, quite visibly moved. What I had just seen was an original and beautiful exercise in filmmaking, and so what if it wasn’t perfect? It is more deserving of its attention than anything Hollywood has churned out in a long time, a work that can’t be held up against a necessarily traditional rubric. A little while later, I came to an additional conclusion about my pastime. Next season, I’ll just have to remember to keep my expectations, and my inner critic, from getting the best of me.