Soft Skull Press, the independent book publisher that’s made a splash with books by everyone from Maggie Estep to Genesis P-Orridge—and has a burgeoning line of gay fiction titles—has another potentially intriguing series underway. “Deep Focus”—touted as “A Novel Approach to Cinema”—pairs established fiction writers with movies that speak on some level to their hearts. Whether the films have had a direct influence on their fiction, or if the movie’s just a longtime favorite, Deep Focus offers a chance to reappraise a dimly-remembered film and/or get to know authors like Jonathan Lethem better.

Clearly patterned after the “BFI Modern Classics” tomes, the Soft Skull titles are slim (if not inexpensive) and focus on one film each. Lethem kicks off the series with John Carpenter’s They Live, while Christopher Sorrentino follows with the Charles Bronson vigilante favorite Death Wish.

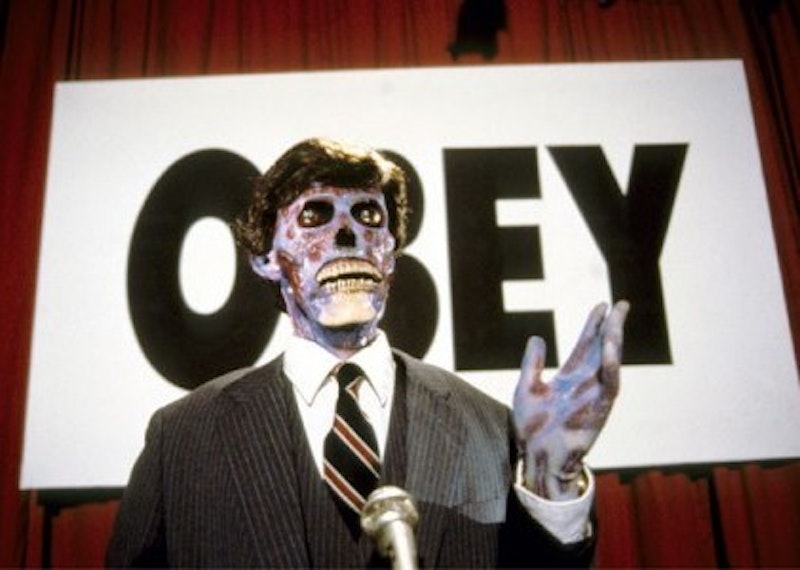

Those selections come as refreshing alternatives to having to slog through yet another exegesis of an already preserved-in-amber film like The Searchers or The Leopard. Lethem in particular makes for a jaunty companion on what is, after all, a pretty jaunty film, breaking his observations into pithily-titled mini-chapters, some lasting a mere paragraph (“Individual Ethics under Late Capitalism”; “Human Power Elite”). He more or less proceeds chronologically through the film, liberally quoting outside sources and taking the time to point out the many incongruities in Carpenter’s work, from the unacknowledged (or is it?) porn-level flirtations between main actors “Rowdy” Roddy Piper and Keith David to the movie’s many liberal visual quotations from the likes of Last Year at Marienbad, Marnie and, yes, The Searchers.

Though careful to examine the film’s many levels—comedy, action, science fiction, political allegory—Lethem always remains mindful of Carpenter’s only semi-serious approach. Having established that They Live’s script prefers to call its secret society of puppet masters “ghouls” rather than “aliens,” he points out: “Ghouls wear wigs. For some reason their masterful illusion-generator can’t do hair. Don’t think about this too hard.”

He also examines the film’s most beloved tropes, from the motivations and characterizations revealed during that amazing six-minute fistfight to breaking down the film’s most famous line, “I’ve come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass. And I’m all out of bubblegum.” Perhaps my favorite point of inquiry is based on Piper’s performance as the otherwise unnamed Nada: “Is Nada the Stupidest Person in the Movie?” It’s all enough to chase you back to another viewing of They Live, if for no better reason than to bask in the presence of George “Buck” Flower once more.

Death Wish is of course an entirely different kind of proposition. Before the series’ sequels became synonymous with brainless action fodder, the original 1974 flick served as something of a political football, its great box-office success being cited as indicative of a rising level of “fascism” among moviemakers and those who flocked to the film. The sainted Pauline Kael was one critic who misread the film as such (and who also erroneously trotted out the “fascism” charge for Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs), but as Sorrentino points out, a careful viewing of the film reveals that it’s anything but.

Unlike Lethem, Sorrentino is an author I’m unfamiliar with. He takes a much more mundane approach in his monograph, and the laughs don’t come as easily as they do in They Live—either film or book. (Rightly so, as the original Death Wish, with its still brutally effective rape scene, is hardly a candidate for ironic indulgence. Death Wish 3, on the other hand…) Though noting Kael’s objections, he singles out New York Times fuddy-duddy Vincent Canby for repeated thrashings; Canby, who apparently claimed he’d never been wrong about a film, probably deserves it, but Sorrentino’s attack seems almost personal.

One of the charges leveled at Death Wish at the time of its release was how its portrayal of New York City as a mugger’s paradise—one where you could barely walk down the street without being accosted—was “unrealistic.” Sorrentino argues persuasively against this viewpoint—the film’s always struck me as more a fable than a documentary—but again beats the point to death. He’s on safer ground when discussing the film itself, making the case that director Michael Winner could actually be artful if given the chance, and singling out the terrific performances by Hope Lange and Stuart Margolin. (Bronson is, as always, underrated.) Even for its apparent stodginess, Sorrentino’s tome similarly encourages revisiting its source, which momentarily turned Bronson into a box-office champ for mostly the wrong reasons.

Soft Skull is a bit soft moving ahead, however; its next titles will dissect The Sting and Lethal Weapon, a pair of films that hardly need re-evaluation. Personally I’d like Deep Focus to stick with something like The Last Wave or The Shooting, but for now am content to keep an interested eye on how the series develops.

Thinking Hard About Some Under-Appreciated Classics

Soft Skull Press' new film crit series shows promise.