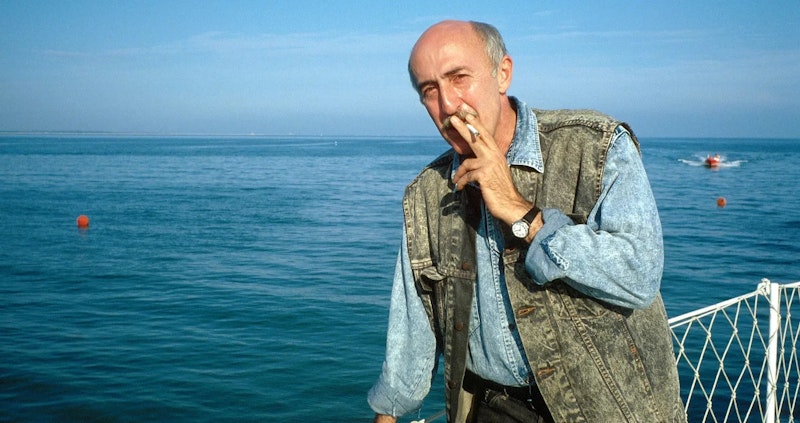

On December 17th, Otar Iosseliani, one of the greatest Georgian filmmakers, died at the age of 89. In the English-speaking world, he languished in a certain ex-Soviet obscurity—more famous than his contemporaries who never left Tbilisi, less acclaimed than those who made films in Moscow, and best remembered outside of his home country for his integration into the Parisian film scene (he’s one of the few contemporary Soviets mentioned in Serge Daney’s essential Cahiers-era collection The Cinema House & the World, precisely because he was no longer Soviet). Iosseliani reinvented himself for the Western film industry, not unlike his co-expat Andrei Tarkovsky, who was rather effusive towards Iosseliani’s work—a rarity for Tarkovsky in talking about anything coming out of the USSR.

What grabbed Tarkovsky about Iosseliani’s films was a strand of poeticism seeping up through the old calculus of montage and “socialist realist” cinema that the Soviets pioneered. While Eisenstein’s mathematical approach to filmmaking reflected scientific nature of Marxist-Leninism that was the epistemology of Stalin’s era, it was the poetic naturalism of Aleksandr Dovzhenko (who was one of his teachers at VGIK, Moscow’s famed film school and the oldest of its kind in the world) that would go on to captivate the generation of filmmakers breathing new, explosive life back into the cinema of Khrushchev’s Thaw.

It wasn’t just the poetic legacy of Dovzhenko that Iosseliani picked up on at VGIK; he also studied under Mikhail Chiaureli, the Georgian filmmaker favorite by Stalin after seeing his 1942 epic Georgi Saakadze. Chiaureli is most famous for directing Stalin’s 70th birthday present, The Fall of Berlin (1950), which cemented that a Georgian couldn’t just run the largest country on earth, but also the full might of its film industry. Iosseliani was part of a cohort of Georgians that would define the new generation of Soviet filmmakers, all of them spiritually fore-fathered by Chiaureli and jumped into gear with Mikhail Kalatozov’s stunning post-Stalinist turn away from dusty, old Socialist Realist aesthetics. Like the death of Agnès Varda and Jean-Luc Godard severing a physical connection to France’s New Wave, Iosseliani’s death leaves all but the 90-year-old Eldar Shengelaia as the only living connection to the greatest generation of Georgian filmmakers who ever lived—his brother Giorgi Shengelaia passed away in 2020 at 82, Georgiy Daneliya died in 2019 at 88, and Marlen Khutsiev at 93 that same year. Yet they’re survived by their cinema, which will last forever.

In less than a decade, Iosseliani released three of Georgia’s greatest masterpieces. His feature debut, Falling Leaves (1966), concerns a young man finding his way through modern Tbilisi by getting a job at a local winery. The film is prefaced with a brilliant (dare I say Dovzhenkian) silent sequence of the traditional regional winemaking process, something which dates back before history itself. The images of villagers stepping on grapes, making chacha from the pomace, and aging the wine in clay qvevri laid in the ground, and then throwing a big supra when the job is done is as essentially Georgian a set of imagery has ever been in cinema.

Iosseliani contrasts this for the rest of the film with the hustle and bustle of modernity, something he’d expand upon in Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird (1970). Here the young man at the heart of the film isn’t naive, but disaffected—he’s a no-good man-about-town who can’t show up on time to his job at the orchestra. If the opening of Falling Leaves is classically Georgian, Once Upon a Time is contemporarily; taking a scalpel to the contrasting ancient Kartvelian culture with the nascent modernity of a Soviet city, all seen through Iosseliani’s flowing camerawork and breezy editing. His final homegrown masterpiece before his expatriation was Pastorale (1975), taking those young city-folk of the day and plopping them into the beautiful, basically primeval countryside at the base of the Caucuses.

What’s revealed in those mountain valleys is the essentiality of specificity—Iosseliani’s early films are so deeply of their time (Soviet), of their place (Georgia), yet universal. Pastorale is about the divide between rural and urban lives everywhere, and the tragic inability of them being able to understand each other on a fundamental level. Pastorale features one of Iosseliani’s most striking images, perhaps one of the most striking images from any film of the 1970s: a train car flying through an ancient town, the passers in the carriage looking on at the villagers like zoo animals, the villagers looking back at the travelers with resentment.

When I first heard the news of Iosseliani’s passing I did a quick Google search on it, and found less English-language results from publications than could be counted on one hand, even including the official release from the Prime Minister of Georgia. It’s a tragedy that he wasn’t known more in the West in life, but perhaps in the tragedy of death can come a new interest, a new generation of cineastes discovering his indelible work for the first time.