By the 1980s popular filmmakers and major studios had created a science to determine what films could generate massive profits and widespread acclaim from fans and critics alike. The Indiana Jones, Star Wars, and Terminator franchises were breaking box office records by giving some of the creakiest pop cinema tropes a high-tech sheen of special effects and superstar performers. Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were obsessed with campy serials and vintage comic strips. James Cameron and Dino De Laurentiis traded in macho ideas from European sword and sandal pictures and 1960s sci-fi. Their fantasy blockbusters spawned countless second-tier imitators. These pictures shared swashbuckling action, dangerous stunts, and other bells and whistles that made them easy to sell. These elements remain iconic in today's Hollywood fantasies.

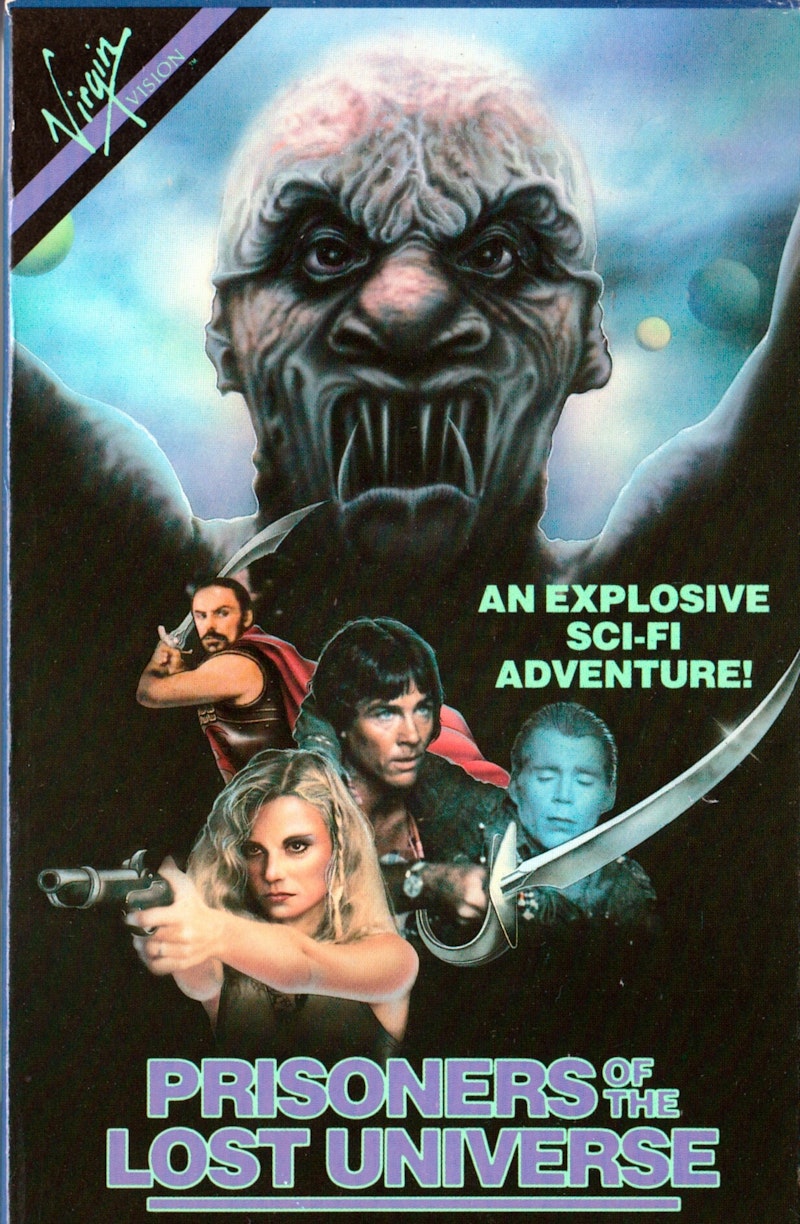

1983’s Prisoners of the Lost Universe was a warped byproduct of the manicured flash that drove big-budget fantasy films. Its visionary chaos marries the roughshod style of cheesy/pre-1960s “back lot epics” and the grandiose sweep of 80s blockbusters.

Terry Marcel directed, co-wrote, and co-produced Prisoners. This wasn’t the first work he’d created that was both goofy and challenging. In the 1970s Marcel began building a resume that pushed the boundaries of the traditional fantasy narrative. He produced the experimental 1977 feature Prey, a queer-themed British sci-fi film whose script was written concurrently to its production. Jane And The Lost City was a 1987 film Marcel directed; it was an adaptation of a risqué comic strip that ran in the UK’s Daily Mirror during World War II. It’s impossible to take of any his films too seriously. The lack of solemnity mirrors the ridiculousness and impossibility of Marcel’s plots. Actors wisecrack and cuss a blue streak, logical continuity is ignored, and clear scientific explanations aren’t even an option. You either suspend your disbelief and enjoy the ride, or laugh at the rampant blasphemy applied to mythic plot points that’d only be coddled by a normal fantasy filmmaker.

The best thing about Prisoners of the Lost Universe and other Marcel works is that, despite their embrace of camp, they weren’t a precursor to today’s horror cinema. Marcel can’t be blamed for Snakes on a Plane or Sharknado. Even though you can laugh at the wackiness of this work, it’s Prisoners’ highly original, energetic visuals that make it amazing.

A big component of that involves casting choices. While you won’t find Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sly Stallone, or Carrie Fisher, the movie does star several popular TV actors including Richard Hatch of the original Battlestar Galactica, Kay Lenz of the 1970s Rich Man Poor Man II mini-series, and veteran heavy John Saxon (well known for guest starring roles in CBS’ Wonder Woman series, The Six Million Dollar Man, and a myriad of westerns, crime shows, and TV movies). While Hatch, Lenz, and the rest of the cast lean hard and loose into the fourth wall, Saxon’s tech-obsessed warlord Kleel is a no-nonsense De Sade wannabe. His defiant megalomania juxtaposes the other performances which all resemble the work of sugar-binging elementary schoolers LARPing at recess.

This can’t be stressed enough: there’s no point in trying to understand the film’s story. Even though monsters, magic, interdimensional travel, lasers, random explosions, martial arts, high speed action scenes, fascist technocracy, ancient folklore’s Green Man, vulgar jokes, PG-13 sexuality, and hilariously fake-looking props all push Prisoners into the realm of escapism, the narrative is no more or less flimsy than that of the fried experimental work created by Matthew Barney, The Kuchar Brothers, or Adult Swim’s more sci-fi influenced creators. If you love the colorful action of vintage comic books and 1980s sci-fi blockbusters just as much deconstructionist cinema, Prisoners of the Lost Universe is destined to be your new favorite post-modern mutation.