This is part of a series of posts on 1960s comedies. The previous post on Breakfast at Tiffany's is here.

"You might as well like yourself. Just think about all the time you're going to have to spend with you," Julius F. Kelp (Jerry Lewis) says in his nasal voice at the end of The Nutty Professor (1963). "And if you don't think too much of yourself, how do you expect others to?" It's a fairly standard Hollywood moral about self-love, self-acceptance, and self-empowerment. And, as with most such Hollywood morals, it's hypocritical, since the range of selves that are acceptable is much more circumscribed than the narrative admits.

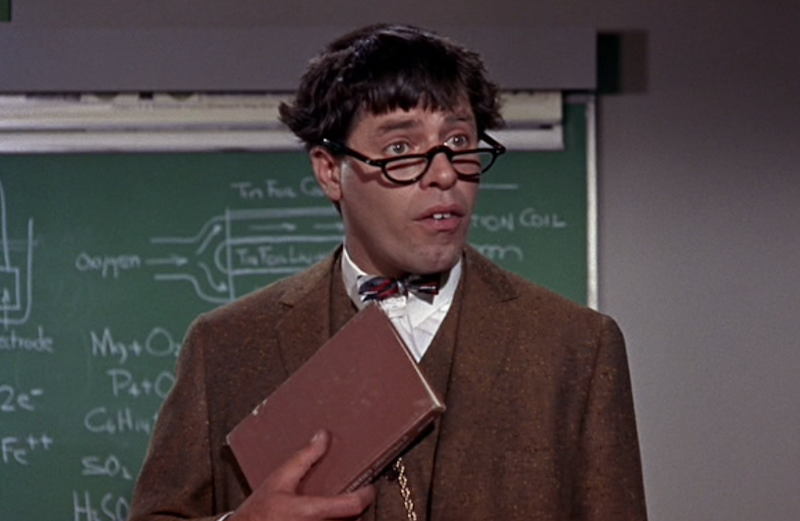

On the surface, The Nutty Professor is about a nerdy, geeky intellectual who wants to become a cool he-man hipster. Kelp is a buck-toothed, bespectacled, whiny-voiced egghead at a local university, who stumbles and stutters from one humiliation to another. He’s bullied by the college president, his own students, and just about everyone except for his va-va-voom student Stella Purdy (Stella Stevens.) To become more manly, and court Stella, Kelp develops a Dr. Jekyll formula which transforms him into a smooth-voiced, stylish, cigarette-smoking teen idol named Buddy Love. Love bullies other guys and fascinates Stella. But ultimately she prefers the cringing, kind-hearted Kelp. The professor decides to scrap his formula and embrace his nerdiness; for his honesty and self-affirmation, he, inevitably, gets to marry Stella.

Lewis-enthusiast Jonathan Rosenbaum sees The Nutty Professor as a mockery of Americanism, which "shows the world just how embarrassing being an American can be." More specifically, the film can be read as a parable about the dangers of assimilation into the much-vaunted American melting pot.

Kelp is a hyperbolic portrait of the emasculated Jewish male intellectual—weak, cringing, and sexually repulsive. Buddy Love, on the other hand, is an image of all-American masculinity—brash, self-confident, and sexy. But Lewis, the child of Russian-Jewish immigrants, presents the white assimilated American as a mean-spirited bully, and the Jewish nerd as sympathetic. Stella breathily tells Kelp that intelligence is the most attractive quality in a man; ultimately, the professor is not only kinder, but also sexier than his alter ego. How could any Jewish intellectual argue with that?

The film's ostensible admiration of Kelp, though, comes with a lot of caveats. One of the running gags in the film is that Kelp carries around with him a watch that plays the Marine's hymn at deafening volume. The nerdy intellectual has he-man Americanism in his pocket. It's a joke because it's incongruous, and it's making fun of loud American patriotism, at least in part. But it's also a joke because Kelp isn't a rough, tough Marine, and is therefore ridiculous.

Along those lines, it's never clear whether Buddy Love is despicable because he's an ugly American, or whether he's despicable because he's an American with an ugly ethnic background. The film delights in showing the instability of the Buddy persona. He's just about to sweep Stella off her feet, when he starts croaking and whining like the sniveling Kelp. Or else he's on stage singing "That Old Black Magic" when his voice changes and he has to scurry for the exit. Scenes like this seem less like a condemnation of Buddy as jerk, and more an expression of anxiety about Kelp's inability to pass as Buddy. Buddy’s condemned off to the side for being a jerk, but the real energy of the film goes into sneering at him because his transformation into a jerk is incomplete. He's still haunted by a nerdy Jewishness he can't cast off.

Nor is the film very convincing when it half-heartedly makes the case for that nerdy Jewishness. Buddy Love is kind of awful. He's conceited; he mocks waiters; he punches out a student who accosts him.

But is Love really more terrible than Kelp? Lewis has said that Love was meant as a portrait of obnoxious hipsters—but he also noted that fans seemed to like the character, and that he didn't end up being all that evil. The professor, meanwhile, conducts unauthorized experiments, resulting in a schoolroom explosion that threatens the lives of his students. He also conducts experiments on himself, without any oversight—again, a serious breach of scientific ethics. And he pursues a relationship with a student in his class, even explicitly treating her with favoritism (he lets her retake a test).

This is all supposed to be funny and cute because Kelp is such a powerless loser; when he imagines Stella with a skimpy bikini and a come-hither stare, it just shows how ridiculous he is. But the truth is Kelp is not powerless; he's a professor with considerable ability to wreck Stella's school career, if he wants.

Kelp's actual actions are more reckless and immoral than Buddy’s; he's not ethically superior to his alter ego. But he's such a caricature that he doesn't have any ethical standing; you can't condemn a cartoon. But neither can you point to a cartoon as a strong statement of self-affirmation.

In any case, that strong statement of self-affirmation starts to look less structurally sound the more you put pressure on it. Kelp's abandonment of Buddy isn't really an abandonment of the ethos of assimilation. Kelp gets rid of his formula when he realizes that he has a better path to mainstream masculine status and success than the one that Buddy offers. The whole point of Buddy was to woo Stella, the all-American young blonde.

Stella is the American dream in herself—and one that the film treats with reverence. She's innocent and kind, but also cool and popular. In wooing her, Kelp woos America, and wins it. Kelp is supposed to accept himself, and so achieve happiness. But the dream of wedding a stunning younger blonde starlet is so thoroughly conventional, it reverses the putative moral. Kelp achieves self-confidence in the conventional Hollywood manner, by possessing the icon of non-ethnic America. Once he's done that, why wouldn't he love himself?

There's nothing wrong with Jewish men marrying non-Jewish women; it's worked out for me. But predicating the humanity of Jewish men on exogamy is something else—not least because it treats women as status symbols rather than as people. Kelp hates and pities himself; Stella’s there to soak up his lust, abuse and insecurity and turn him at last into the man he wants to be—which is a man who’s validated by catching a woman like her.

Kelp's Jewishness is never explicitly spelled out, and you could make an argument that he stands in for a different kind of outsider. He might be an immigrant, for example, or a gay closeted man, with Buddy Love as his fabulous velvet-suited secret identity. The ambiguity is intentional and necessary. If the film were about a specific kind of not belonging, rather than a generalized failure of masculinity, it wouldn't be funny (to the extent it can be said to be funny in the first place.) The nutty professor can't be too nutty; he can like himself only so far as he doesn't really tell you whom it is he likes. And as long as he marries the blonde.