When I first watched Orson Welles’ film, F for Fake (1973), I turned off the television and said, “What did I just see?” I confess that Welles has become an obsession and that this film left me slightly confused, yet I loved it. Even the first viewing mesmerized me by the images and frames rapidly moving on the screen. Although not immediately, I watched this mysterious and unique film five more times. And the more I watch, the more is revealed. But is it really a cinematic revelation or is Welles playing a masterful trick?

When it came out, F for Fake didn’t receive the acceptance that Welles had hoped for. In a commentary, which is part of The Criterion Collection’s release of the film, Peter Bogdanovich notes that he tried to help Welles but had a difficult time distributing the film in the American film market. In fact, when he screened it for one of the American distributors, the executive fell asleep in the middle of the film. Was he an unintelligent viewer? Was Welles’ project a complete failure because it could not reach the mass audience? Or was Welles trying to do something entirely new in the development of the cinema? Most critics, at this point, agree that he created something unique, “a film essay.”

What is so strange and seducing about this film? On the surface, the story is about two people and their relationship. First, we have Elmyr de Hory, a famous art forger, whose entire character revolves around lies, deceit, trickery, and false existence, a Hungarian who’s serious about the pronunciation of Buda-pesht and not Buda-pest (I mention this because Elmyr de Hory deems it important: “being Hungarian is not a nationality. It’s a profession.”). The camera follows Elmyr as he strolls around the streets of Ibiza and holds lavish parties at a gorgeous villa, which turns out he doesn’t own.

The second faker is Clifford Irving, a writer who became notorious by composing a biography of the famous recluse, Howard Hughes. Except the biography was a complete hoax and Irving never had any access to Hughes whatsoever. He paid for it by going to prison for almost two years.

The interviews of Elmyr and Clifford were mostly filmed by a French producer, François Reichenbach, and Welles assembled them into his own cinematography. In the interviews, both assert an air of superiority and have no qualms or remorse about what they’ve done. “I don’t feel bad for Modigliani,” says Elmyr, “I feel good for me.” For both of them, this wasn’t a moral issue at all. And it would appear not for Welles either. But is Welles a scoundrel, like Elmyr and Clifford? Why should it matter what kind of person Welles is in this film? It does, because Welles, in his typical theatrical fashion, inserts himself in every frame (whether visually or merely by the means of the sound).

Back to my original question: what’s this film about? Is there a beginning or an end? Is there a middle? The answer is absolutely. But like a great jazz composition, the film moves backwards and forwards in time, while time itself is perpetually undefined. It may make us uneasy but the perception that this film is merely chaotic and haphazard is false. There are many beginnings and middles, and Welles tells us so. He even assures us that he’ll show a film in which “everything…I s strictly based on the available facts.”

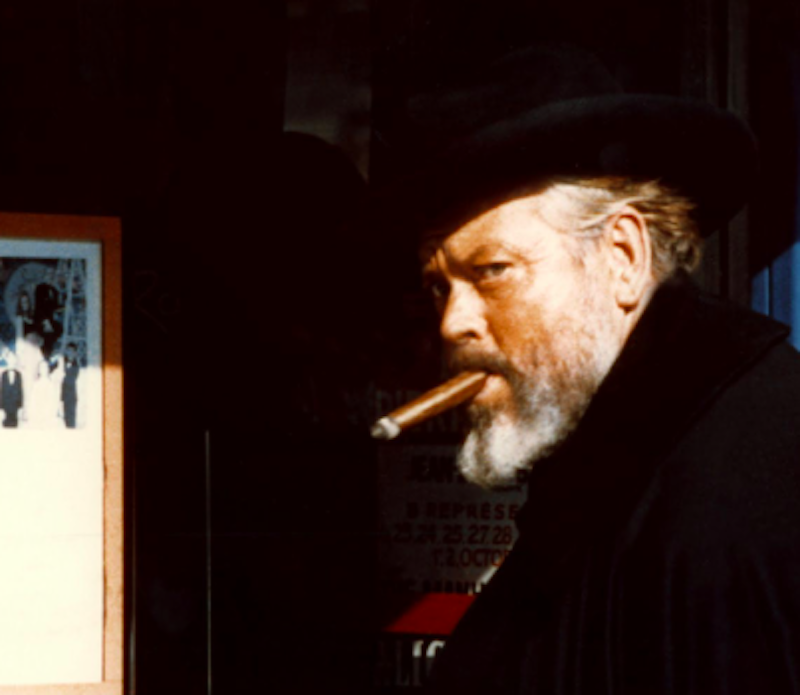

A towering figure of Welles covered in a magician’s cape is the first thing we see. He’s performing a magic trick for a couple of children. “Ladies and gentlemen,” begins Welles, “by way of introduction, this is a film about trickery and fraud, about lies.” His partner at the time (or mistress), a Croatian actress, Oja Kodar, looks at him from the train: “Up to your old tricks, I see.” “Why not? I’m a charlatan,” says Welles.

Why is he calling himself a charlatan? Is he really serious? Could this be a commentary on the fact that he was kicked out of the American cinematic establishment and found home in Europe? Is F for Fake attempting to be a European auteur film, with sexy sounds of Rhodes piano? Or is Welles an American through and through, disguising himself in the cloak of European sensibility and perhaps existential sentimentality?

Welles is brazen in his film, especially when it comes to showing off Oja Kodar. Her face, hair, and entire body are photographed from every possible angle. She’s a beautiful woman, and Welles has no problem indulging in what seems to be an older man’s obsession and possession of a younger woman. Kodar is, at times, an erotic object for men to ogle and also Welles’ young lover.

I ask again, what is this film about? Fakes everywhere. Fake art, fake biographies, fake artists, fake writers, and most of all, fake experts. Welles has no mercy for the so-called experts: “Experts are the new oracles. They speak to us with the absolute authority of the computer.” Of course, Elmyr has a complete contempt for the experts and art critics: “[They] pretend to know something what they only know superficially.” This is mostly true. Experts tell us all the time what to do with our lives and do we really question them? Welles insists that “Man cannot escape his destiny to create whatever it is we make—jazz, a wooden spoon, or graffiti on the wall. All of these are expressions of man’s creativity, proof that man has not yet been destroyed by technology. But are we making things for the people of our epoch or repeating what has been done before? And finally, is the question itself important? The most important thing is always to doubt the importance of the question.”

Any artist is burdened with constant thoughts about the external world. He doesn’t know if what he’s creating is true and most of all, new. But why, as Welles suggests, are we so concerned with whether our output is new or never-before-seen? Is it the critics we’re so concerned with? An acceptance from the establishment and audience? Does any of it matter? Shouldn’t the glory of creation be enough to the point where the question of who created it doesn’t matter at all? Chartres, as Welles notes, has no creator that we know. Yet, there it is, solidly standing in time and timelessness designed and built by the human mind and the human hand.

Despite the fact that Welles does play a harmless trick on us toward the end of the film, his constant narration presents him as a guide through this ridiculous series of hoaxes. He’s amusing yet disorienting. We assume he’s telling us the truth because he’s the director, the master charlatan, and the magician but are we being dupes by believing Welles? Even when he’s serious about the “facts,” even when he appears to be laughing and ethically commenting on Elmyr’s and Clifford’s foray into fakery, Welles retains that mischievous look on his face. His voice, his eyes—they seduce (even with that fat body underneath the cape), yet the seduction remains alive right next to the knowledge that his face is behind a metaphysical mask. He appears to be our co-conspirator in the revelation of these “available facts,” yet the careful editing of the images conceals the truth andthe lies, and the only thing that’s left is Art. But is that bad?

It would be foolish to assume that F for Fake is only about art and forgery. It’s also about who we are. Are we fakes with one another? And are we fakes with our very selves? Is our life just one big lie? Is our face constantly masked? Are we engaging in the duplication of masks that Nietzsche so eloquently writes about and reminds us of the real, perennial, and existential problem. How many masks are we creating as we fall deeper and deeper into the fakery and our own lies until the human face is nothing but a distant memory, or worse, a mirage in the desert?