The Sundance Film Festival is an institution that no longer has interest in supporting challenging cinema. Films from 2024 that landed distribution deals fell within familiar genres; A Real Pain was a classical road trip buddy story, Didi was a charming coming-of-age tale, Exhibiting Forgiveness was an emotional family drama, and My Old Ass was a wacky comedy with a science fiction slant. These films deserved the attention that Sundance granted them, but the festival has also become a void in which films that dared to push boundaries are left to die.

2024’s festival saw the premiere of Little Death, the directorial debut of Jack Begert, with Darren Aronofsky as a producer. The satirical dramedy featured a bifurcated narrative that tackled two of the most critical issues within America today; the loss of creative individualism in media, and the horrors of the opioid crisis. Begert turned his sights on the worst of America, but unlike other kaleidoscopic ensemble pieces like Traffic or Margaret, Little Death doesn’t have a protagonist who could generate sympathy. It’s a bleak, cynical film that rivals Aronofsky’s Requiem For A Dream or Pi in terms of consistent misery.

Perhaps the only way a film as blatantly non-commercial as Little Death could wrangle a halfway decent budget is the involvement of a recognizable face, even if it’s one that has been out of the spotlight for some time. David Schwimmer has benefitted from Friends’ consistent circulation for decades, but outside of a few memorable roles in Band of Brothers and Curb Your Enthusiasm, his career hasn’t been interesting. Perhaps it’s stunt casting, but Schwimmer is perfect as Little Death’s Martin Solomon, a disheveled filmmaker whose pent-up frustrations reach a breaking point when he’s told that his project will be altered.

Although comparisons could be drawn between Schwimmer’s performance and various “difficult” filmmakers that are active in the industry today, the difference is that there’s no indication that Solomon has any talent. His stories are personal, drawn from his childhood, but there’s nothing that suggests that he’s the next Christopher Nolan. While it’d be possible to empathize with Solomon if he was burdened by integrity, Schwimmer has indicated that the character is a sullen, sexist provocateur who has mistaken callousness for wisdom.

The question that Little Death asks is an interesting one; if artistic individuality is of such value, should that freedom be extended to those who lack the talent? Solomon’s under the impression that the world needs to hear his story, and becomes flummoxed when he’s told it’d be more agreeable if his self-insert of a protagonist is played by a woman; this is embodied by a memorable moment in which Schwimmer is temporarily replaced by the underrated actress Gaby Hoffman. The loaded commentary could’ve been taxing if that was all Little Death had to offer, but the use of creative animated segments, odd needle drops, and trippy visual anecdotes is enough to sustain the narrative momentum.

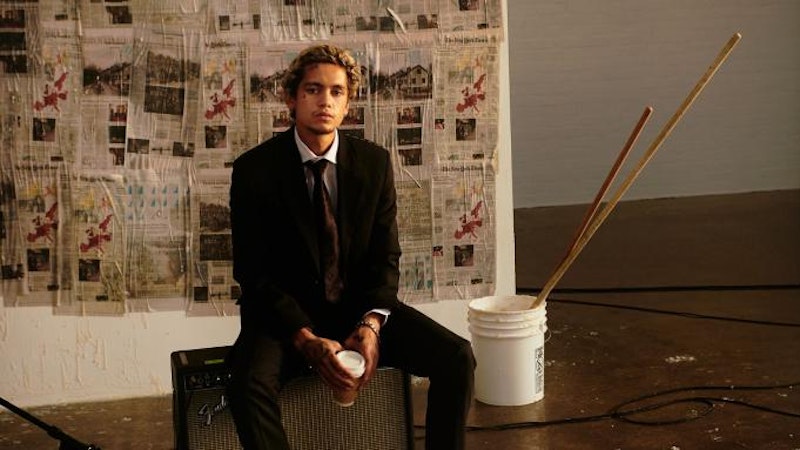

Begert understood how intolerable it’d be to spend an entire film within the company of Schwimmer’s obnoxious performance, because Little Death is also centered on two addicts who come to grips with reality after a botched robbery. AJ (Dominic Fike) and Karla (Talia Ryder) begin as the type of goofy stoners that could’ve popped up in a Kevin Smith film, but they eventually face a crisis that’s far more grounded. These aren’t complex characters, but they’re not just plot points either. Begert’s interested in how the opioid crisis has robbed young people of their futures.

Both halves of Little Death reach the same conclusion—the infrastructure of American society today doesn’t support lessons being learned. Solomon’s trapped in a cycle of self-congratulation and suppression; any success he’s granted will satisfy his egotistical projection, but setbacks will serve as fuel in his argument against “woke” politics. Similarly, AJ and Karla are in the midst of a heist that never ends, as opioid addiction only ends in forceful separation or death. Should they actually begin the recovery process, they’d be forced to assess how much of their lives have been wasted in search of the next hit.

It’s not surprising that Little Death didn’t attract any attention from buyers like Netflix or Prime Video, as it's not a film that’d stand out on a streaming interface. The divisive response from initial critics indicated that its awards prospects were slim, which may have dissuaded a theatrical-focused distributor like Focus Features or Fox Searchlight from even paltry offers.

Most films don’t deserve awards, and they usually don’t make money either; that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be seen. The worst byproduct of internet film criticism is that whenever quantitative values are assigned, audiences assume that they’re under no obligation to engage with something that they’ve already written off.