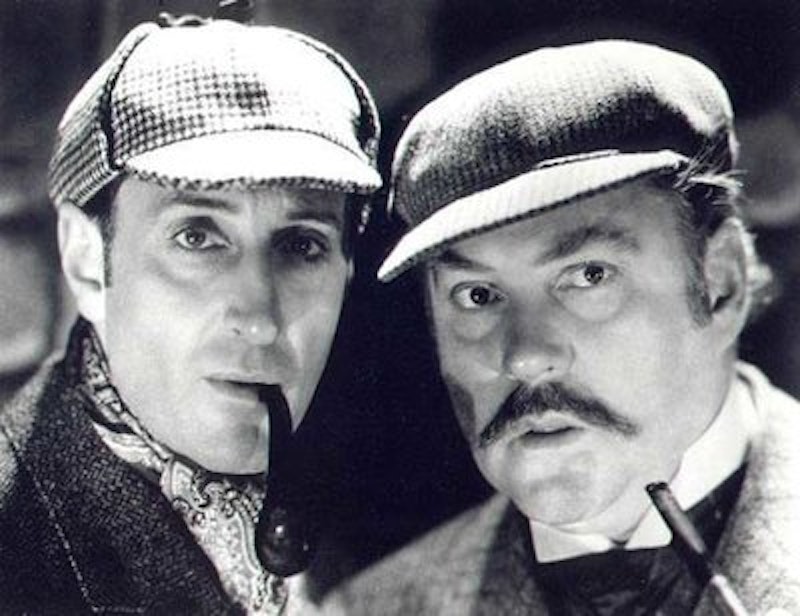

The black-and-white Universal Pictures logo spins around a globe and a fanfare plays. But no monsters here, nothing that won’t be proven human. Fog fills the screen, then shadows and the feet of two standing men. Pan up: one’s slack-jawed, rounder in the face, moustachioed, older. The other eyes the camera warily, unblinking, magnetic: thin-faced, hawk-nosed, a pipe between stern lips. Music swells and dissolve to their shadows, and the credits we already know, that we can tell at a glance. Basil Rathbone as Sherlock Holmes. Nigel Bruce as Doctor Watson.

The two actors made 14 films as the famous duo between 1939 and 1946. The first two, The Hound of the Baskervilles and The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, were big-budget A-pictures made by Fox. The studio chose not to go on with the series, but after a radio series featuring Rathbone and Bruce was successful, Universal picked up the film rights to the Holmes stories and again cast the two men in their now-familiar roles. Roy William Neill directed them a dozen times, in settings updated to then-modern times. The first three pitted Holmes against German agents, including the despicable Professor Moriarty. Though watchable, there’s something slightly off about them. When Neill became producer as well as director, starting with Sherlock Holmes Faces Death, the series became more gothic, setting Holmes against evil in manor houses and isolated villages, taking full advantage of sets originally built for Universal’s monster movies.

Some of the Universal films very loosely adapted Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories, giving them new structures and a 1940s polish. At the same time, the films have an identity of their own—partly, perhaps, because of their limitations. These were B pictures, cheap movies turned out to fill the bottom half of a double bill, if better funded and more prestigious than most. The Holmes pictures had higher-quality acting than most B movies, which is part of the reason why they hold up today—Rathbone simply is Holmes, the definitive interpretation of the Great Detective, with Jeremy Brett in the Granada TV series of the 1980s and 90s his only real rival. But watching Rathbone’s Holmes films now, they also work because of the sheer craft to them, the directorial skill that manipulates light and camera and design. That’s Neill’s work, and it’s worth talking about.

Consider The Scarlet Claw, often said to be the best of the Universal Holmes series. The opening shots are like something out of the “Night on Bald Mountain” sequence in Fantasia: a nighttime wasteland; a small church with a bell tower and cemetery, surrounded by bare-branched trees reaching to it with fluid limbs, everything drowning in mist and night; a bell tolling; a village under a church spire. Cut to a local inn, then inside, where everyone’s silent as the bell echoes. Pan across the motionless locals in the barroom to a brightly-lit man looking uneasy. He walks away from camera, which moves to find a man entering the room and follows the newcomer as he walks past foreground objects: a stove, an unmoving waitress.

Dialogue sets up the story, establishes character. The mystery of a tolling bell, a priest who doesn’t believe in ghosts. A weird glow on the marshes; dead sheep. But the scene’s really been made by the visuals. Not just the eerie establishing shots, but the overall craft. The atmospheric lighting, with heavy shadows out of a Halloween story. The camera moving across the tavern, setting up the people and the scene, letting us drink in a sense of place. And keeping things visually interesting. A little later a dialogue scene inside a manor house is established by a crane shot, then framed by a lamp and the side of a chimney. There’s a consistent vocabulary in these films of high establishing shots, of Dutch angles, of elegant little tracking shots and, always, images of Rathbone in profile: widow’s peak, sharp nose, bony cheeks, Holmes through and through.

There’s a lot more in The Scarlet Claw typical of the series, if perhaps more accomplished than usual. The series used different cinematographers with each installment, but always striking and dramatic lighting. An example in Claw is a moment when a mysterious figure comes to Holmes’ room at the inn; he’s seen first as a shadow passing along the wall like something out of Nosferatu. Darkness lies heavy all across this movie, palpably dark even in its restored version on DVD. You wonder how it played 70 years ago.

There’s a clever attention to detail, sets dressed with remarkable detail for a B picture, filled with elaborate props. You can see it again and again in the films: scenes in castles, manor houses, auction houses, museums, even (as here) the sadly-fictional Royal Canadian Occult Society—all these things look like the most lavish possible versions of what we might expect. Walls are decorated with elaborate wallpaper, boast paintings, are given more definition with curtains, bookshelves, grandfather clocks. In Claw, set in Canada, there’s even a mounted moose head.

The budget’s used well and smartly. Look closely, and you might notice a distinctive prop or bit of dressing reused from other films in the series. Look more closely, and you’ll notice the occasional stumble or blown line that there wasn’t time to reshoot on a B-picture schedule. Look extremely closely and you’ll see sets and pieces of the Universal monster movies—Sherlock Holmes Faces Death, for example, uses the crypt from Bela Lugosi’s Dracula.

But mainly if you watch these films you’ll see the craft of classic Hollywood: effective, atmospheric moviemaking on a budget and a tight schedule. The frame’s filled with stuff that tells us where we are, that gives us the feeling of a deliberately unreal place and of the stylized reality proper to Sherlock Holmes. On the one hand, there’s a credibility that comes from simply having background extras walk up and down a set of stairs in a hotel lobby behind Rathbone as he reads a plot-relevant letter. On the other hand, the subtle camera moves themselves frame and flatter the actors. Particularly Rathbone, who seems to pull the camera after him as he strides through the mysteries.

The films are creations of their time, to be sure. Few women, except for villains, damsels in some form of distress, and the matronly Mrs. Hudson. Caucasians, except for unfortunate incidents as when Holmes disguises himself in brownface. At this distance, the 1940s feel almost as archaic as the late-19th century of Doyle’s tales.

But that distance also helps the movies. From Faces Death on, 20th-century elements are used with restraint. There are telephones and electric lights and automobiles, but after those first anti-Nazi films these things rarely shape the story. The films feel like they could have been set in the classic Holmes era, and so get at something of what makes the character work.

Crucially, the 1940s are like the 1890s as a time when logical deduction was enough to explain the world. There’s a faith in human reason common to both periods that’s largely alien today. Contemporary versions of Holmes regularly show him making incorrect deductions, which rarely happens in the Rathbone films. That’s partly a script convenience—the movies are less than 90 minutes long, often less than 75, and Holmes’ ability to see through bullshit drives events like a shot. But it feels significant that the last film, Dressed to Kill, quotes a line from Samuel Johnson: “There is no problem the mind of man can set that the mind of man cannot solve.” These movies were made in a time when human intelligence could (to paraphrase Thomas Mann) will more strongly than fate and thus be fate.

Thus also Rathbone’s Holmes: he’s fallible, but his errors are brought about by the machinations of a rival and more sinister intellect. He’s all reason, saving only a demonic joy in confrontation and wordplay. He’s stern, authoritative, even superhuman. He’s nemesis, unwavering justice in the guise of mortal man. Far from the languorous, bohemian drug addict we sometimes glimpse in Doyle; it’s likely no coincidence that Jeremy Brett’s Holmes explores those aspects much more—you can’t present a better Holmes than Rathbone, only a different one pulled from the same source material.

Bruce’s Watson is a good foil, somnolent and avuncular. He’s nothing like the Watson of the books. But he works as a contrast to this Holmes, particularly when presenting a moment of human empathy that’d come strangely from Rathbone. Previous screen Holmeses minimized Watson, who had no obvious reason to exist when removed from his role as narrator. Bruce reinvented him as comic foil, and his real-life friendship with Rathbone helped seal Holmes and Watson as one of the great friendships in all of fiction. It’s notable that as later Holmeses became more fallible, their Watsons have become more persnickety—a little more like the Watson of Doyle’s tales, with his unexpected vein of pawky humor.

Past the leads, the acting’s stylized, but the point in these stories isn’t subtlety of character. The films used a kind of repertory company, many of the bit parts played by the same actors. There’s a commedia dell’arte effect, as though we watch a cast of murderers, aristocrats, and Scotland Yard coppers always playing out the same stock narratives. That’s not quite the case, but the use of Doyle’s stories as inspiration helps lend the films the feel of twice-told tales. That works, as the murders in these movies feel oddly weightless—not tragedies, but acts signposting evil intent. They establish there’s a bad guy in the world of the film, and we watch the good guy work out who he (or she) is and eliminate the evil.

It’s all tremendous fun, because these movies feature a rare meeting of the right director with the right actor with the right character. The slickness of classic Hollywood is deployed by a master craftsman to tell mystery stories around the archetypal detective, played by a man who looks and acts the living incarnation of the imagined hero. These stories work precisely because they don’t aim at making a great statement about character or theme. They don’t manufacture a love interest or family interest. They’re about Holmes being Holmes. Without Rathbone, they don’t work. Without Neill’s direction, they’re something other and probably lesser. But they have both, and well into another century they’re still the definitive filmed Sherlock Holmes.