In a year that’s seen roughly 30 transgender people murdered, and the LGBTQIA community shift its focus to trans rights after the Obergefell v. Hodges case guaranteed same-sex marriage rights, Tom Hooper’s film The Danish Girl is a slam-dunk piece of Oscar bait. Socially conscious, beautifully performed, and directed with all the schmaltz and pabulum we’ve come to expect from the average Hollywood historical drama. Too bad, then, that it’s a revisionist pile of trash.

Hooper and screenwriter Lucinda Coxon adapted their flick from David Ebershoff’s novel of the same name, which itself was a heavily fictionalized account of the life of Lili Elbe—the first transgender woman in history to undergo sex-reassignment surgery. (Bookish types may remember Ebershoff’s previous novel, The 19th Wife, a murder mystery about polygamy; perhaps it was the smash commercial success of that book which encouraged him to write another novel about people he doesn’t truly understand.) In this account, Lili (Eddie Redmayne) slowly grows to recognize her true identity as a woman while alternately supported and berated by her wife Gerda (Alicia Vikander); the two painters begin as the fondest of lovers and slowly grow apart as Lili comes into her own, a split that inevitably ends in death for Lili, who slips away happy that she is finally “completely [her]self.”

Except all of that is bullshit. The Danish Girl remains mostly accurate through its initial 15-20 minutes, establishing both characters as up-and-coming talents in the European art world and showing us their uniquely playful relationship. But once Lili makes her first appearance, it’s all downhill. Gerda is immediately shuffled into the typical “But I want my HUSBAND back!” role, and keeps a mostly-stiff upper lip through Lili’s transition despite her grief at losing “Einar” (Lili’s former name). In reality, this couldn’t be further from the truth; according to almost every account, Gerda was either a lesbian or bisexual herself (evidenced by the wealth of sapphic erotica she created, which reportedly caused riots), and their marriage remained mostly unharmed for decades. According to trans historian Susan Stryker, who consulted for the film, “She seemed incredibly open to it [Lili’s transition]… That was the feedback that I provided on the script. And I hope they took that to heart.” Obviously, Hooper and Coxon did no such thing—they blatantly ignored it.

In fact, despite The Danish Girl’s stubborn insistence on turning its fascinating subject matter into Generic Trans Tragedy #56, Lili and Gerda lived happy lives together for many years. After Lili decided to live as a woman fulltime, the two moved to Paris, where they could live more openly as a lesbian couple. Gerda threw lavish parties at their apartment, and it was only in 1930 that King Christian X of Denmark discovered that Lili was legally recognized as a woman and forcibly dissolved their marriage. Lili then embarked on a staggering series of five reassignment surgeries over two years, the last of which (a womb transplant) killed her.

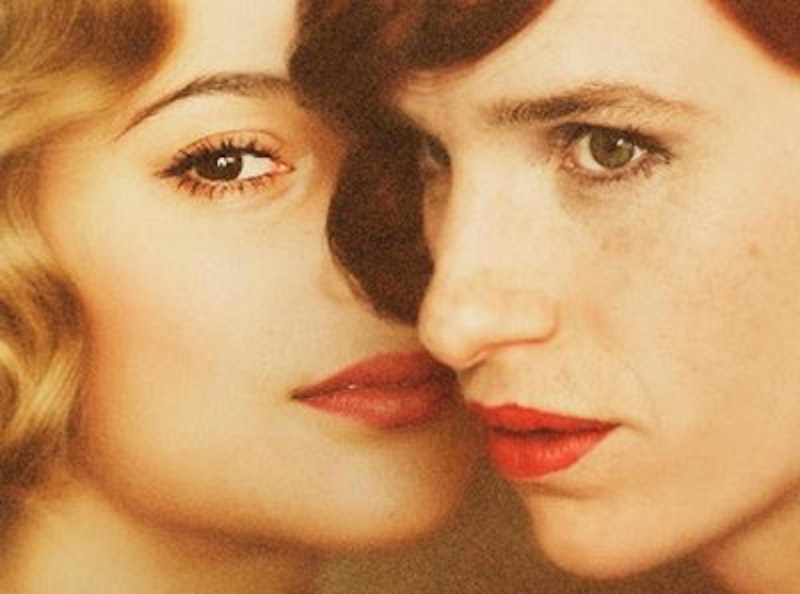

If there is anything to celebrate here, it’s our principal players, Redmayne and Vikander. I feel obligated to compile a supercut of every scene without dialogue, as it is in those moments where the story manages to capture the merest glimpse of the true Lili and Gerda. Redmayne’s emotion is real and raw; his research thorough and earnest. His early look of curious longing at Gerda’s vanity is stirring, and his cautious exploration of his own naked body in a mirror evokes Lili’s artistry—one can sense that Redmayne is analyzing the areas of light and shadow, looking for the brushstrokes on his skin to paint with his fingers. There’s one scene in particular where Redmayne slips into a peep show to learn to imitate the worker’s feminine sensuality, and their cautious game of follow-the-leader that follows is heartbreakingly genuine. It’s nearly impossible for a trans person to see Redmayne as anything other than a man play-acting as (trans) woman, which is a source of intense dysphoria and grief for many in their own lives; but Redmayne comes as close as a cisgender man possibly can to representing this fundamentally different identity.

Vikander is even better, possibly because as a cis woman playing such, she can more naturally inhabit her role. It’s a tragedy that with her talent, Vikander wasn’t allowed to explore the far more complex relationship Gerda truly had with Lili. As it is, Vikander rips her chest open so we can see the very beating of her heart. Her love for Lili and glee at her newfound professional success is constantly at odds with her fear for their future, for Lili’s health—and her fervent wish to go back to the way things were, despite her knowledge that the “old way” was always a lie, even if neither of them knew it at the time. As Redmayne shudders with joy while exploring femininity, Vikander savagely sketches Lili onto her canvas, eyes grim with loving loss, pouring every ounce of feeling into physical art. She embodies creation at its purest in one of the finest performances of the year.

In a way, I wish neither actor had done such a good job. If the acting was as buffoonish as the script, which fundamentally misunderstands 1920s Paris and perpetuates harmful, joyless trans narratives, more influential critics would write this off as another film in the vein of Emmerich’s laughable Stonewall: well-intentioned, but worthless. Instead, cis reviewers around the world will flock to Redmayne and Vikander’s masterful work and prop up The Danish Girl as a watermark in queer cinema, ignoring the countless ways in which it erases the most important parts of Lili Elbe’s existence. There’s nothing past the first act that remotely approaches the true love and companionship Lili Elbe and Gerda Wegener shared. To imply otherwise is an insult to their memory. Eddie Redmayne’s character may be called Lili, and speak some words lifted from her correspondence and memoirs, but she is not Lili, nor is Vikander’s character Gerda. They are shallow imitations, spellbindingly acted but devoid of their fundamental truth. And a trans movie without authenticity isn’t a trans movie at all. It’s a sham.

—Follow Sam Riedel on Twitter: @SamusMcQueen