In 1946, when screenwriter Carl Foreman began outlining his new script for a revisionist Western, the Allies had just won the war and the United Nations was a new entity. Foreman wanted to write an allegory about the need for world unity to defeat unchecked aggression and uphold democracy. The story would be about a lawman recruiting local townspeople to help fight a gang of violent outlaws. Then the Cold War started. The spirit of cooperation between the United States and Russia was replaced by a new era of anxiety and mistrust.

By the time Foreman started his first draft of High Noon, America had shifted right and opportunistic Republicans were accusing domestic communist sympathizers of threatening American freedom. Karl Baarslag of the American Legion said, “A communist is a completely transformed, unrecognizable and dedicated man. While he may retain the physical characteristics of the rest of us… his mental and psychic processes might as well be from another planet.” In other words, communists were like zombies dedicated to destroying the American way of life.

J. Edgar Hoover, head of the FBI, called communists “masters of deceit.” His paranoia had a seed of truth since the American Communist Party did take marching orders from Joseph Stalin. But most American communists were not agents of a foreign power. Like Bernie Sanders supporters today, they were responding to the inequality of American wealth distribution. They desired change through peaceful means, not revolution.

Carl Foreman was a struggling screenwriter. Like many of his peers, he joined the communist party in 1938. “The idea was just in the air,” he said. He quit the party in 1943 after joining the army. During World War II he made military training films with Frank Capra, including writing the film Know Your Enemy-Japan. After the war, he returned to Hollywood and his career took off. He worked with his friend, producer Stanley Kramer, writing the films Champion and The Men (Marlon Brando’s movie debut). Both were nominated for Best Screenplay Awards.

As Foreman toiled on the High Noon screenplay, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) held public hearings into communist infiltration of Hollywood. HUAC ignored Foreman in their first round of hearings in 1947. “I was a very unimportant little fellow,” Foreman said. But as his career grew in prominence, HUAC took notice. In 1951, Foreman received a pink letter in the mail. It was a subpoena commanding him to appear before the committee. Foreman had two choices: confess his communist past and provide names of fellow travelers or plead the Fifth and refuse to answer questions. Option one meant humiliation; option two was career suicide.

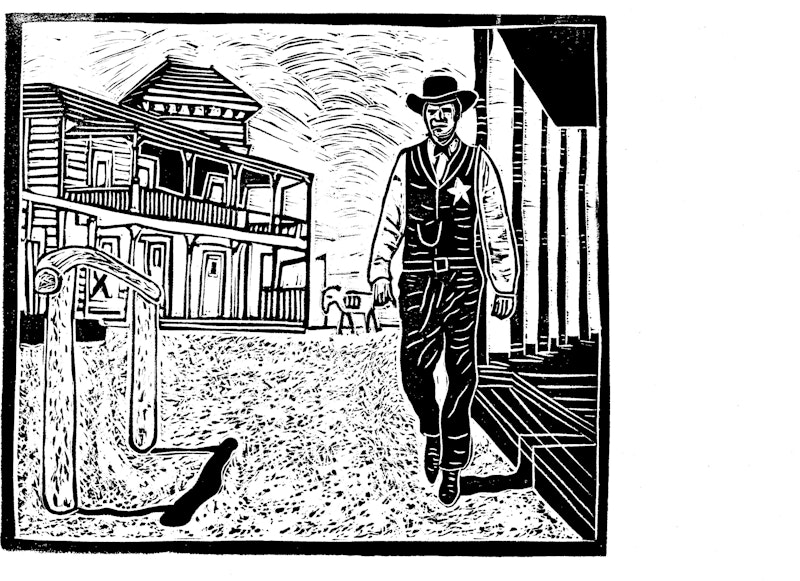

As he contemplated, his High Noon screenplay took a new direction. It became an allegory about the blacklist. Marshall Will Kane (Gary Cooper) was Carl Foreman. The outlaws gunning for the Marshall were the HUAC members threatening Foreman’s livelihood. The cowardly citizens of the small town were Foreman’s Hollywood peers who refused to protest the blacklist. “As I was writing the screenplay, it became insane,” Foreman said. “Life was mirroring art and art was mirroring life… I became the Gary Cooper character.”

The Cold War gained momentum and national sentiment turned against the so-called “reds in Hollywood.” Ten prominent filmmakers (the Hollywood Ten) were convicted of contempt of Congress and sentenced to a year in prison. Stanley Kramer, the producer of High Noon, had a difficult decision. He’d started his own production company and was on the verge of a distribution deal with Columbia. He knew if he publicly supported Foreman, he’d his risk his studio deal.

Foreman tried to convince Kramer to resist the committee. Kramer urged Foreman not to plead the Fifth as if he had something to hide. Kramer felt this would cast shade on everyone involved with High Noon. The two old friends became enemies. By the second week of production, Kramer told Foreman to hand in his resignation and sell his stock options in the film. Foreman refused. He wanted to see the film through to the end. He also didn’t want to testify before HUAC as someone who’d lost the support of his peers.

Foreman was fired. But Fred Zinnemann, the film’s director, and Gary Cooper, the star, objected. In addition, Kramer learned that Foreman never signed a contract deferring his film salary. This meant Bank of America, who was financing the film, could cut off the funding needed to complete production. Kramer had no choice but to rehire Foreman as writer and associate producer. According to Foreman, Kramer told him, “Well, you’ve won.” They met for several hours but their friendship ended that day.

On September 24, 1951, Foreman drove to the Los Angeles Federal Building to testify in front of HUAC. When asked if he was a communist, he said he’d signed a loyalty oath for the Screen Writers Guild stating he was not a communist party member. “That statement was true at the time and is true today,” he said. Committee members asked if he’d been a communist prior to 1950. He invoked the Fifth and refused to answer. He also refused to supply names of other communists.

HUAC members grew agitated but Foreman stood firm. He was labeled an “uncooperative witness.” Days after his testimony, stockholders and company directors of High Noon legally removed Foreman from all involvement with the film. “They threw me to the wolves,” Foreman said. Foreman’s lawyers negotiated a settlement for around $150,000 and Foreman surrendered his Associate Producer credit.

He was at the peak of his craft and one of the best screenwriters in Hollywood, but Foreman was blacklisted and unable to find work. Frustrated, he moved to London where he’d live and work for the next 25 years. In 1956, he co-wrote The Bridge Over the River Kwai. The film won a Best Screenplay Oscar but due to the blacklist the screen credit went to Pierre Boule, author of the novel that inspired the film. Not until 1984 did the Motion Picture Academy finally recognize Foreman (and co-writer Michael Wilson) as the true screenwriters. Foreman died of a brain tumor a few months before receiving his belated Oscar.

High Noon was released in 1952 and was a smash success among moviegoers and critics. The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards including Best Screenplay and Best Picture. President Eisenhower loved the movie. Ronald Reagan called High Noon his favorite film. So did Bill Clinton, who screened the film in the White House 17 times.

Not everyone was a fan. John Wayne, a conservative and anti-communist, called High Noon “the most un-American thing I’ve seen in my whole life. I didn’t think a good marshall was going to run around town like a chicken with his head cut off asking everyone to help. And who saves him? His Quaker wife. That isn’t my idea of a good western.” Howard Hawks also made his 1958 film Rio Bravo in response to High Noon. He agreed with Wayne that the film's ending was unrealistic, and at odds with the Western genre.