I am struck by awkwardness.

Over the past few years, it’s grown in literature and film. Character, dialogue, camera work, diction—directors and authors have taken up an itchiness of form, an aesthetics of awkwardness.

I was watching a 12-minute movie the other day, Death To the Tinman, directed by Ray Tintori, which got me thinking. Tintori is a New York director, 24, a film graduate of Wesleyan. Death To the Tinman received Honorable Mention for Short Filmmaking at Sundance and was included in Issue 5 of Wholphin, a quarterly DVD magazine of short film. The movie is a bit out of synch, the timing and pacing very self-conscious and clumsy, the acting a bit forced. Nonetheless, it’s pretty effective filmmaking.

The film is an adaptation of Frank Baum’s book The Tin Woodman of Oz, which tells how a lumberjack became the Tinman, losing his heart along the way. Instead of a world of Munchkins and flying monkeys though, Tintori's is a place of fundamentalist preachers and socialist revolution. The woodsman is a rebel, stealing from the rich to give to the poor, collaborating with an iconoclastic inventor and his flying machines. He dates the preacher's daughter, despite hellfire condemnations from the pulpit. When the preacher puts a spell on the woodsman's ax and it chops off its wielder's arm, the inventor fashions him a new one of tin. As the woodsman continues to sin, more amputations and more tin, follow on.

At first blush, the awkwardness of the movie seems the result of the filmmaker's inexperience. The leading scene, the first beats of dialogue, are forced, the characters push their lines at each other, reacting rather than interacting. The camera appears uncomfortable with the actors' faces and bodies, wandering about as if trying to stay out of their way. Considering the director's age, the fact that Death To the Tinman was his senior thesis in college, this reaction could seem justified. As the movie continues, though, and we get a feel for these characters and their world, that clumsiness begins to make sense. It's a styled awkwardness. It opens the characters up, lets us share their feelings and experiences.

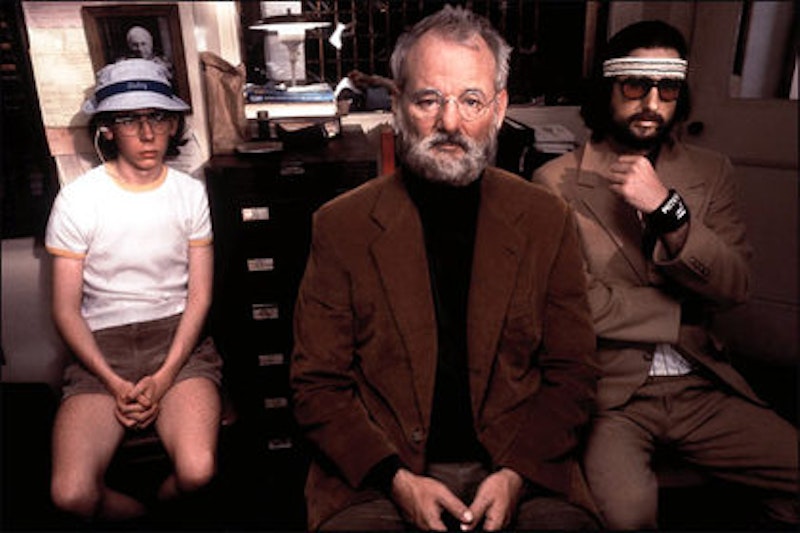

Perhaps what this clumsiness gives us is an answer to realism, an alternative to the clean lines of production and form that predominate in film. The most well known dissenter from realism, the auteur of the awkward, is Wes Anderson, director of The Royal Tenenbaums and The Darjeeling Limited. He's made a career out of a clumsiness of direction, his actors bumping against each other like overstuffed couches. His characters don't so much relate to one another as provide running, sequential soliloquies. And there is something to the brightly colored sets, the camera work, that contributes to this itchiness; nothing is settled, we viewers are kept fidgeting in our seats. The visuals, acting, dialogue, they don't let us get comfortable, and we are never completely swept up by the story.

The way Anderson's, and Tintori's, characters deliver their lines sets them apart, both from each other and from the action. This staginess cuts through the narrative dream and keeps us aware of the movie we are watching. In a strange way, the result is that we’re better able to see who these people are. As the awkwardness of the characters builds, we look past the story, past even the characters' actions, into their thoughts and feelings. The self-consciousness of the story gets around the problem of the film being a film, the seamless design we've come to expect from a movie, resulting in the unexpected.

As the Tinman reaches the point where he is more metal than flesh, his double, the Meat Puppet—made from the woodsman's body parts left behind at the morgue—moves in on the preacher's daughter and takes the Tinman's place in her heart. To win her back, the Tinman starts a revolution, installing the inventor as mayor of the city. The town devolves into violence and chaos, as the Tinman aches for his lost love.

The initial awkwardness at the film's start doesn’t let up. The inventor continues to chew over his lines, the composition remains angular, and the love scenes stay tentative and faltering. And yet, we feel ourselves falling for these characters; the style becomes infectious. It succeeds in fumbling past our objections by giving us raw feeling.

What's interesting, and revealing, is that this aesthetic is as much a trend in fiction as film. Young writers like Tao Lin offer similarly stylized action, clumsiness of diction, in the same hope of getting past the story, circumventing realism. Lin provides unadorned, painful loneliness, the characters all left feet and sore hearts. His novels are halting and disjointed, bits of suburban life interrupted by hallucinatory fantasy. In fact, his work reads much like the scrolling of an 18-year-old boy's daydreams, all clumsy desire and shapeless fear. And again, it’s strangely effective.

Still, many people have problems with this kind of writing, these kinds of movies, often objecting that the awkwardness is a put-on, a cleverness that's too self-consciously quirky to take with any seriousness. The lonesome boys running into talking hamsters as they deliver pizzas in Lin's novel, Eeeee Eee Eeee, aren't real enough for us to care about them, his critics say. And they have the same problems with Anderson's movies, or Miranda July's, claiming it's all just too trendy, oddity for odd’s sake and at the expense of the audience.

But what exactly is this interest in clumsiness? Critics might say it's the fault of fashionable magazines like McSweeney's, Dave Eggers and his hipper-than-thou sensibility. It's postmodernism run to its final absurdity, irony and detachment more important than human experience. It's the tongue cluck of sarcasm beneath the surface of hipster literature and scenester film.

And yet, Death To the Tinman is nothing if not earnest. The woodsman's heart bleeds in front of us, his loneliness blunt and raw. If the acting and directing are to be criticized, it should be for too much emotion, not detachment. Its clumsiness isn't ironic, we aren't supposed to snicker over the funny camera work and primitive special effects; we're supposed to feel them.

What these filmmakers look to be after is a way of busting through realism to get at essential human emotion. The movies are often filled with weirdly fantastical elements, and this helps to displace our usual attitudes to story too, but it’s the awkwardness, the staginess of the production that ultimately opens the characters up. There is a produced feeling, surely, a postmodern self-consciousness, but it's not irony these directors are after, not cool detachment. It is awkwardness—deliberate, affected, and raw—that is the ideal.

That Was Awkward

How unfinished conversations, poor camerawork, and clumsy characters can actually reveal deeper emotions.