I couldn’t help but feel sorry for the director Ang Lee when plans for this summer’s new movie, The Incredible Hulk, first leaked. For all of his own 2003 Hulk’s problems—it was painfully long and ignored the comic’s original story, for starters—it remains overly maligned, and this new movie, starring Edward Norton as Bruce Banner, so consciously aims to avoid its “mistakes” that I wouldn’t be surprised if all remaining DVD copies were being systematically bought and burned by Marvel Enterprises.

If you thought that Lee’s film took too long to set up the back-story, you’ll be pleased that the new film distills all necessary exposition into the wordless opening credits. If you thought Lee’s Hulk looked too green and cartoony, the visual effects team for Louis Leterrier’s new version have gone out of their way to darken the beast, adding veins and texture until he now looks like a ‘roided-out cousin of the cinematic Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, or even the more reptilian specimens of the Gremlins movies. The 2003 film was self-consciously styled like a multi-panel comic book, but the new movie goes even deeper into Hulk-specific lore: they repeat the 70s TV show’s gimmick of having Banner’s eyes turn green, the beast himself is voiced by that show’s Hulk, Lou Ferrigno (also present in a cameo), and there’s a pretty funny play on the show’s famous “You wouldn’t like me when I’m angry” tag line. Leterier and his screenwriter Zak Penn even repeatedly address the most nagging suspension-of-disbelief problem with the Hulk story—do his pants grow with him, or what?

But other than that, the 2008 Incredible Hulk is summer action movie business-as-usual. Leterrier’s not a bad director, and I do credit him for keeping his blockbuster to a relatively svelte 114 minutes, but movies like this don’t even feel like products of actual filmmaking. They feel like unconscionably loud assaults on the senses, focus-group tested to appeal the broadest possible audience in order to recoup their bloated budgets. Is it faint praise to say that The Incredible Hulk is a decent-to-good movie from a hollow, worthless genre? Indeed it is, and it’s the most honest praise I can muster.

For the unfamiliar, the Hulk is one of the Marvel Universe’s most tortured and sad inhabitants. Poisoned by gamma radiation during a government weapons experiment, scientist Bruce Banner discovers that when his pulse goes over 200 beats per minute, he transforms into a massive, destructive green beast that stands about ten feet tall and can throw an 18-wheeler like Nolan Ryan threw fastballs. These rampages are also out-of-body experiences for Banner, however, and during one he injures his colleague and romantic interest Betty Ross (Jennifer Connelly in ’03, here played by Liv Tyler). Ross’s dad happens to be an army General, however, and the one in charge of the gamma experiment at that. He orders the U.S. Army to capture Banner by any means necessary in order to harness his powers for artillery purposes.

All superhero myths deal with the protagonists’ balance between their capacity for greatness and their desire for “normal” existence, but the Hulk may be the only character who seems genuinely disgusted with himself. Banner spends most of his screen time lamenting his lot and trying to permanently rid himself of his superpower: “I don’t want to control it, I want to get rid of it,” he tells Betty in the new movie. As for that power itself, it’s pretty unfulfilling as they go; once the pulse hits the danger zone, he goes on a destructive spree, his skin impervious to all army firepower, and the whole event ends with him in exile from humanity. Audiences are left to sympathize with a guy who’s either beleaguered and unhappy or monstrous and destructive. As a character, the Hulk is somewhere between King Kong and a recovering alcoholic, complete with violent blackouts (the new film even has a recurring “Days Since Last Incident” ticker); that’s manna for adroit comic makers like Hulk creators Stan Lee and Jack Kirby—not to mention the solitary, young readers who buy them—but it’s a lot of sturm und drang to foist on pleasure-seeking moviegoers. Somehow people still blamed Ang Lee for failing to rake in tickets five years ago.

The obvious solution for getting people excited about a Hulk movie is therefore to up the destructive ante and turn the monster’s bouts of rage into cacophonous CGI symphonies indistinguishable from whatever other special effects-laden nonsense is competing for theater space. Leterrier even added another Hulk-sized villain, his main comic book nemesis Abomination. Played by Tim Roth, Abomination is the gamma-infused version of government bounty hunter Emil Blonsky. Blonsky’s a power-hungry type who willingly undergoes a procedure to transform himself into the Hulk’s equal, but who cares? Whatever motivation or characterization there is behind the Blonsky character, it’s all just buildup to the inevitable 500-decible dogfight that ensues between the monsters in Act Three.

I was entertained by The Incredible Hulk—occasionally even exhilarated by Leterrier’s sweeping shots of the Brazilian shantytown where Banner hides out—although I mainly felt condescended to. For a movie concerning government tampering and rife with topical issues (what is the Hulk if not a potential WMD?), this is a profoundly safe movie. Everything in the film, from the chemistry-less love story to the second-act comic relief of Tim Blake Nelson’s scientist role, feels like the product of a terrified and cowardly marketing research team. And that’s the problem with movies like The Incredible Hulk: they are products first, and necessarily so. Hundreds of millions of dollars are pumped into these summer blockbusters, so the emphasis has to be on pleasing as many people as possible: genuine comic fanboys, girls and women, young children, fast food and toy companies looking for tie-in bait, Generation-X moviegoers who grew up with TV show, and of course television syndication distributors. The scripts therefore become a mishmash of romantic yearning, pubescent angst, easily identifiable good and bad characters, and special effects sequences that bludgeon everyone in the theater as if to remind us, “You Are Being Entertained Now.” Hulk and Abomination even rumble in front of Harlem’s Apollo Theater, lest the audience forget that it’s showtime.

Much has been made of younger generations’ supposed immunity to screen violence thanks to video games and mass media, but what of the more general audience desensitization to this empty form of entertainment-as-bludgeoning? Every time a CGI creature like Leterrier’s Hulk wreaks havoc in a recognizable metropolis, movie audiences lose a little bit of appreciation for what a subtle art the suspenseful set piece really is. Contrary to current popular belief, sensory overload has very little to do with it; the ear-splitting volume and computerized shots of industrial shrapnel flying towards the audience may work in a post-THX multiplex, but they don’t tease or excite our sense of human drama.

I was in a half-crowded bar two weeks ago, just enjoying conversation with friends, when one of the employees had the terrific idea to scratch whatever Food Network rerun was on the TV and pop in a DVD of Jaws. Spielberg’s 1975 masterpiece is the original summer blockbuster, and yet it’s astounding to see how little resemblance it bears to this era’s crop of supposed crowd-pleasers. The TV was on mute, yet you could overhear every bar conversation slowly acknowledge Jaws’ presence in the room. Even without John Williams’ famous score, Spielberg’s visual sense is hypnotic and tense on its own. You can watch the drama of the movie unfold without any sound at all (or, in the case at hand, with decontextualizing background chatter and bar music) because Spielberg’s camera so perfectly frames the drama. Whether shooting from the shark’s perspective or letting the frame bounce with the waves while aboard Robert Shaw’s skipper, Spielberg continuously uses visuals to heighten the sense of fear in his movie, making the shark a threatening, lurking presence in the film even though we don’t see it for nearly an hour.

Most importantly, Spielberg knew (and knows) that fear and suspense are emotional states as well as physical ones, and as such are heightened when the onscreen dangers happen to characters we actually care about. Hence the relative visual calm of his movies compared to The Incredible Hulk; he isn’t afraid to pause and let his characters converse or laugh. To act, in other words, which is a sorely missing element in our current conception of summer blockbusters. When everything—both the budget and screen time—is subservient to CGI-created characters and events, the best a director can hope for is that his film will have a few years of good DVD sales before people move on to the next punch in the face. Too bad for Ang Lee.

The Hulk is a tricky commodity to pull off in this form: the pain at the heart of his character seems to require a director who’s willing to take audiences to a psychologically difficult place, but the physical aspects of his character require CGI mayhem and at least three long sequences of him throwing cars. The closest that any modern superhero movie has come to obtaining this balance is Christopher Nolan’s Batman Begins from 2005. Nolan performed the revisionist feat that Leterrier was supposed to achieve, only going in the opposite direction. He did away with the gloss and one-liners that ruined Joel Schumacher’s abysmal Gotham City attempts and instead embraced the extreme psychological darkness at the Batman myth’s core. Then he hired a fantastic crew of actors, minimized the forcefulness of his special effects, and shot a visually compelling movie filled with shadow and fog. It was a movie for people who cared about Batman, not a Batman movie for the biggest possible audience.

The new Incredible Hulk isn’t a Schumacher-level disaster, but it’s a complacent film, maybe even a step backwards. Ang Lee at least attempted to shake up the summer-movie conventions to which Leterrier hews so closely. The Lee version was a noble failure, but it at least had vision. Edward Norton, who also helped write the script and served as a general artistic guide for the new film, seemed like the right guy to return the blockbuster formula to its humanistic Spielbergian roots; he showed impeccable understanding of the best 1970s Hollywood conventions in the criminally under-appreciated 2006 film Down in the Valley. But alas, no matter how much money this new Hulk may make, it isn’t a memorable film in any important way. It’s symptomatic of a larger cultural expectation for relentless, soulless action during the summertime, and an unfortunately spineless homage to the dark vision of Lee and Kirby. Save us, Dark Knight.

That's Entertainment?

A new Incredible Hulk movie assaults viewers like a giant green fist to the face, but that’s apparently what we crave in the CGI era.

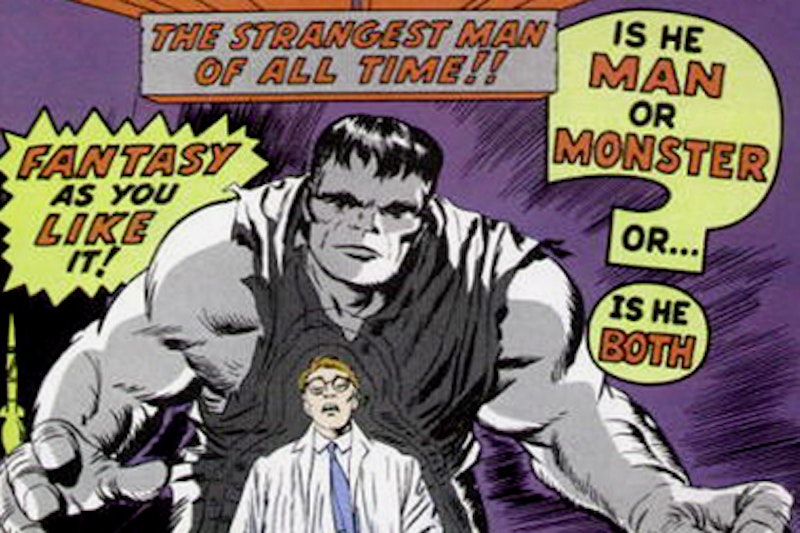

Simpler times: A detail from "The Incredible Hulk" #1, May 1962.