Stanley Donen’s 1967 film, Two for the Road, stands out for many reasons. It bends the genre of romantic comedy, takes the plot line and presents it in a non-chronological way, and blends both American and European film elements to achieve a unique artistic coherence. But that isn’t all: much like in Fred Zinnemann’s The Nun’s Story (1958), Audrey Hepburn takes on a role that expands her acting range. She leaves the wardrobe of the quiet sophistication of Givenchy we see in Charade (1963), and exchanges it for Paco Rabanne’s cool indifference.

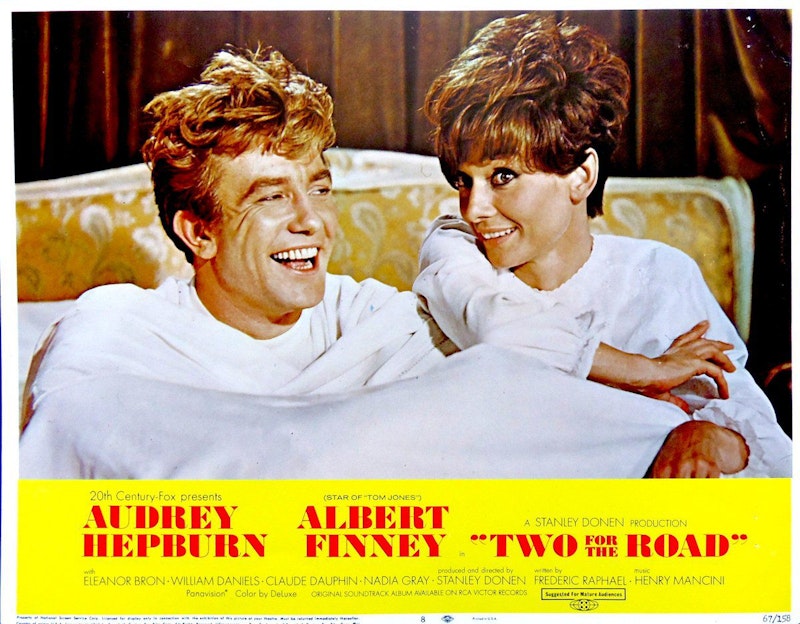

Hepburn plays Joanna Wallace, with the incomparable Albert Finney as her husband, Mark Wallace. The film opens with the couple in a car driving through France, hoping to reach the Italian border soon. They’re cold to each other, and begin to reminisce about their marriage. The relationship is clearly falling apart, and Joanna and Mark are wondering whether they should stay together. Years into it, and with one daughter, they realize it’s not easy getting rid of old habits, which seem to include love itself.

As they drive through France, the film cuts back and forth to when Joanna and Mark met, loved, fought, had extra-marital affairs, and how Mark’s work as an architect ended up as an imposition on the relationship. Yet this isn’t a film about divorce or a loveless marriage. The two keep sticking with each other. Joanna likes the lifestyle that Mark has brought to them but that came at a price. He’s essentially a kept man by Maurice Dalbret (Claude Dauphin), a wealthy businessman who arranges for Mark to have work. Joanna hates this yet she can’t deny that the wealthy lifestyle is something she wished for.

It’s an odd relationship. Right from the beginning, Mark doesn’t really want her, and prefers Joanna’s friend, Jackie (the beautiful Jacqueline Bisset). But Joanna keeps hanging around. Mark warns that he’ll be unfaithful and that she won’t be able to rely on him. But Joanna doesn’t care. Despite the low self-confidence, Joanna still has some kind of power over Mark. He knows that he won’t be able to stay in any relationship long enough so perhaps, in some way, he’s resigned himself to being with Joanna. Yet, Joanna’s charm keeps throwing him off.

On the surface, fast cars, cool 1960s fashions, European lifestyle, and Henry Mancini’s beautiful music score may be the primary elements of the film. There’s no doubt that Hepburn’s style and Finney’s irritable attractiveness play a part in making this film unique. But it’s also a commentary on the modern perception of marriage. How can a couple were in love with one another suddenly begin to hate each other with such passion? Are these to be accepted forms of marriage? Are people simply typologies that one marries?

Some of these issues get examined a bit more in Joanna’s and Mark’s encounter with Cathy and Howard Maxwell-Manchester. Played by Eleanor Bron and William Daniels, they represent a different kind of marriage: one of convenience and decisions based on social and economic standing. Cathy, who was in a relationship a long time ago with Mark, tells him that Howard is the “marrying type” while Mark is the “lover type.”

The four (along with Howard’s and Cathy’s spoiled daughter Ruthie) are traveling around Europe but things are tense. Not only is there a specter of Mark and Cathy’s relationship that’s haunting the tourist enterprise, Howard and Cathy have a different view of marriage and child-rearing. They treat Ruthie like royalty, and act on any silly or stupid whim she has. Apparently, they feel like they have no right to impose any rules on her, and she needs space in order to emotionally mature.

Howard’s also in “analysis,” yet another indication of the modern marriage that rejects religion or tradition as the guide through the relationship. Laying on the psychiatrist’s couch is a far better “confessional” for the modern couple, yet the Maxwell-Manchesters have problems of their own.

Howard’s organized and fastidious. Cathy likes this but only because of the sense of security. Throughout the trip, she throws it in Howard’s face that Mark is her “favorite beau,” yet Howard’s unfazed. As tensions mount, the real breaking point comes when Howard tells Joanna that she resents Ruthie because she represents the child that she wishes to have. In addition, it’s Ruthie who spills the beans in the end, revealing that Cathy called Joanna “a suburban English nobody.”

This is the only instance in the film when Mark defends Joanna but such events and emotions are rare. Is there anything that Joanna and Mark can hold onto in order to save their marriage? Is calling each other “bitch” and “bastard” both aggressively and endearingly enough to save the marriage? Is there nothing that’s bigger than their egos that can balance these two people?

Donen never sacrifices romantic comedy for drama, yet the subtext is always present. It’s a dark film, and brings out a different aspect of Hepburn’s performances. One can’t help but think about the tensions she was experiencing with her then-husband, Mel Ferrer. The marriage was dying, and the chemistry between Hepburn and Finney is undeniable. Perhaps this contributed to Hepburn’s understanding of Joanna’s personality and choices she made.

Two for the Road is a good companion to Donen’s Charade and William Wyler’s 1966 How to Steal a Million, but it carries a darker message. It’s not just about the star power and elegance of Audrey Hepburn. That glamor takes on a secondary role. Donen chooses to examine the pitfalls of marriage, which isn’t grounded in anything solid, and thus offers an important commentary on the evolving culture. Hepburn and Finney prove to be the exquisite vessels of that cultural examination.