The French New Wave finally made its way to Africa in the late-1960s thanks in part to the French postcolonial presence on the African continent, which gave rise to the particularly influential artistic output of directors in Senegal, with films like Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Touki Bouki (1973).

Though originally a commercial flop, and previously only available in low-quality VHS releases, Touki Bouki was one of the first films restored in 2008 by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, which “preserves and restores neglected cinema from around the world.” Now in streaming format on the Criterion Channel, we can all see Mambèty’s brave film in a modern context.

Mambèty’s non-linear tale shows two college students, Mory (Magaye Niang) and Anta (Mareme Niang), scheme to steal some money, but after that plan fails, the two wander (and wonder) aimlessly around post-colonial Senegal. Repeating and spatial incongruities form Mory and Anta’s fantasy landscape, as they attempt to break free from their colonial consciousness. The real daring of Mambèty, though, is in his stark refusal to be a propagandist.

Past critics have noted that Touki Bouki represents an aesthetic counterpoint to what is called Third Cinema, post-colonial cinema best represented in films like Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (1966) and Ousmane Sembène’s Black Girl (1966), two films with explicitly revolutionary politics, their aims toward anti-capitalism and, ultimately, decolonization.

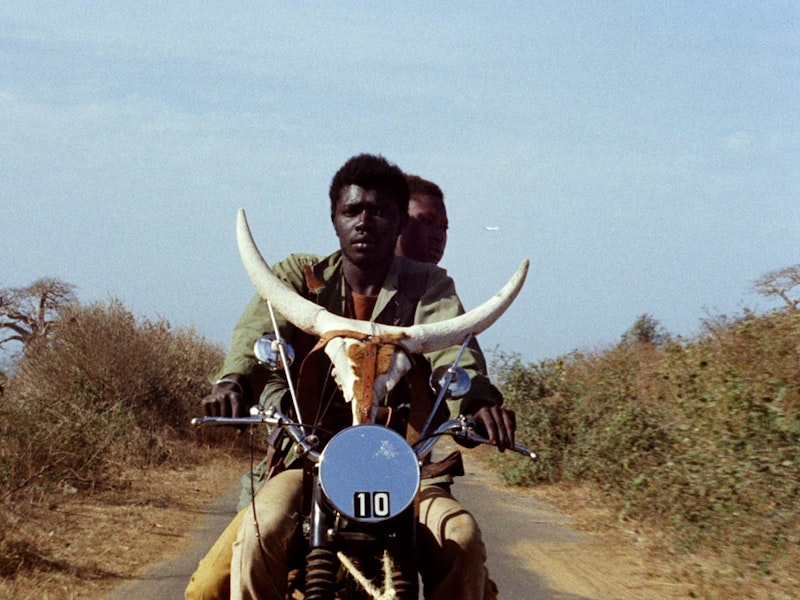

In Touki Bouki, Mambèty’s filmmaking is ambiguously political; he refuses to make the sort of political statements that in many ways defined Francophone African cinema. This isn’t to say that Mambèty is apolitical; certainly, the images of violent animal bloodletting (such as when cattle are slaughtered and a goat’s throat is slit) and the film’s famous bullhorns, Mambèty’s images of fate, say otherwise. The representation of left politics in the film, signified by a group of hostile revolutionaries who hassle Mory and Anta, shows total defiance towards an African intellectual elite.

That’s because Mambéty’s goals in Touki Bouki weren’t unequivocally political. Using the road genre, a love story about two university students, Mory and Anta, Mambety’s camera syncretizes two different cultural practices—the aural and the aural-visual—into a distinctly African style of filmmaking that re-contextualizes them both.

More recently, Touki Bouki has entered the public consciousness, through its appropriation by wealthy artists Jay-Z and Beyonce. In 2018, the couple recreated an iconic image from the film—with protagonists Anta and Mory on their fledgling motorcycle with mounted bullhorns—in a poster for their On the Run II tour. Like Mory and Anta, whose daydreams blend fantasy and reality in post-colonial Senegal, Beyonce and Jay-Z’s recreation hoped for a diasporic effect, suggesting they, too, are runaways.

In one scene, Anta and Mory pull a heist; they steal a wealthy gay man’s car (he then calls the police and flirts with the investigator), nabbing some of his clothes, too. The joyride takes place on an empty road, heading into town. Mory emerges, naked, on top of the car, and begins a hostile-yet-not-angry speech. Mory declares victory over all his foes, real or not, describing in detail how he wrestled his way to the top. Intercutting the sequence are shots of children running alongside the car. But the camera reveals that these children are a fantasy, Mory’s imagined audience. The result is a scene that’s a great act of myth-making.

The stolen car, painted in red, white, and blue, provides Mambèty perhaps his most daring image of rebellion, an image that not only re-contextualizes the African story-telling tradition of Griot storytelling in post-colonial France but also reminds the audience of an American and British colonial past. Mory's naked oration mixes personal fantasy with colonial history, an appropriation of oppressive symbolism that now provides, at least for a moment, the feeling of freedom, pre-Oedipal plenitude, where anything and everything is possible.

Mory’s griot, though not a strictly traditional griot performance, nevertheless syncretizes Senegal tradition with a then-contemporary postcolonial subject’s desires—a representation of what scholars David Murphy and Patrick Williams call in African post-colonial cinema the “griauter,” a hybridization of the African (griot) and Western (auteur) storyteller. As the film intercuts the car and children sequences, he creates a mythos of victory—of conquering through wrestling—with masculine self-assurance. It’s a distinctly African sequence, transformed by both histories of European colonialism and technology. Mambèty’s filmic equivalent brings African tradition to European film and European film to African tradition.

Mambèty’s daring in this scene reveals the importance of that kind of brazen freedom that most Americans are afraid of having, let alone reflected back at them onscreen. Mambety’s hybrid style is, on its face, typical of the categorizations applied to African filmmakers whose styles combine the West with the Global South. Yet his execution and craftsmanship, his awareness of both African and European filmmaking styles, is unique.

He never makes overt political statements, unlike his contemporaries. But, for the viewer, Mambety’s understanding of the post-colonial situation, its politics and cultural impact, is intuitive and instinctual. Now we can all appreciate Mambèty’s cheekiness.