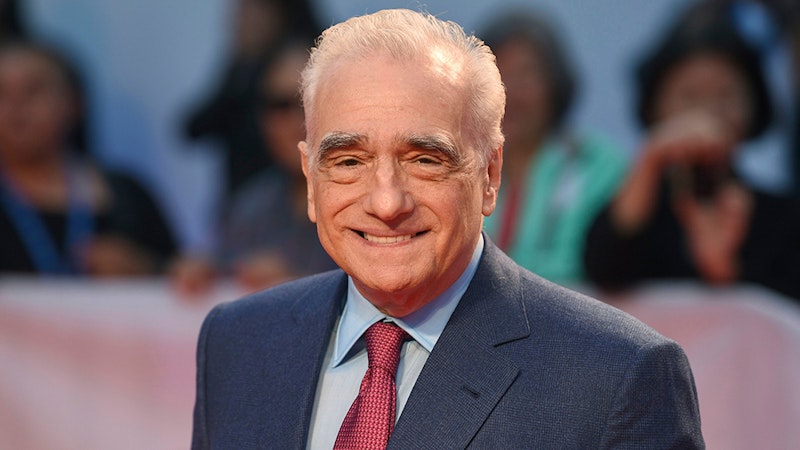

Martin Scorsese has caused a stir on social media and the film world by criticizing Marvel movies. In an interview for Empire magazine, Scorsese said, “I don’t see them. I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

This comment prompted a response from Joss Whedon and James Gunn defending the franchise. Reflecting on Scorsese’s work, Gunn said he “was outraged when people picketed [Scorsese’s film] The Last Temptation of Christ without having seen the film,” and he’s also “saddened that he’s now judging [Gunn’s] films in the same way.”

Scorsese wasn’t trying to pick a fight with anyone. His comment was simply a response to a question by an interviewer, and he wasn’t “picketing” superhero movies in any way. Scorsese was making an aesthetic judgment. Are we so uncomfortable that we can’t have discussions about art anymore? Does everything have to boil down to an emotional response, in which we imply that someone’s aesthetic judgement is “not nice” or not “woke” enough? In addition, this behavior has destroyed talk or creation of artistic standards. In today’s equalizing society, everything is great, and nothing or nobody is better than something or somebody else. This kind of attitude toward art and excellence has mostly generated mediocrity.

Scorsese’s comment may have been just a quick response to a question but it reveals his view of film. In order to not get offended (as if that should matter), one has to understand what Scorsese means by “cinema.” In a moving essay, “Standing up for cinema,” Scorsese reflects on the power of the moving image and what kind of impact it’s made on him. Scorsese was inspired by film, and what he saw “illuminated something within” him. The images he saw were a gift—“a means of understanding and eventually expressing what was precious and fragile…”

Scorsese contemplates the meaning of one single image (“The baby carriage rolling down the Odessa Steps in Battleship Potemkin,” or “Peter O’Toole blowing out the match in Lawrence of Arabia”) and how beautiful and extraordinary and awe-filled it can be. But there’s more to it. What about the second image? And the third? And the fourth? What happens when they are connected? For Scorsese, this connection of celluloid is a metaphysical connection between the filmmaker and the images.

Scorsese is moved by the process of editing: “One image is joined with another image, and a third phantom event happens in the mind’s eye—perhaps an image, perhaps a thought, perhaps a sensation.” Scorsese is implying that there’s a phenomenological component to making and viewing films. The filmmaker has to be open to what’s unfolding before his eyes. This “collision of images” is a fundamental part of cinema according to Scorsese, and furthermore, “this is where the act of creation meets the act of viewing and engaging, where the common life of the filmmaker and the viewer exists, in those intervals of time between the filmed images that last a fraction of a second but that can be vast and endless.”

In other words, there’s an existential component to film, and this is especially true when we view it. This isn’t to say that we’re not engaging in any way with a Marvel film, but films such as these are rarely about the interior lives of characters. Everything about them is directed outwardly. They can be fun, and as Scorsese has said, well-made, but the question is will we go back to them in order to unravel and uncover yet another meaning we may have missed upon first viewing?

Such films have their place but can we really say that their importance or meaning should be treated the same way as, for example, Ingmar Bergman’s work? They can’t be viewed in the same way, with the same mind’s eye, that we would approach Cassavetes, Kubrick or Scorsese. I wouldn’t sit down to watch Cassavetes’ A Woman Under the Influence (1974) expecting some old-fashioned entertainment. Rather, I watch it with an understanding that this will be a demanding experience, that when Cassavetes challenged himself and his actors also challenged his audience.

What Scorsese encapsulated in his statement about the Marvel franchise is that we need to go back to acknowledging aesthetic standards. His statement may sound elitist but we shouldn’t see it as that. It’s true that Scorsese is not in favor of democratizing cinema but his idea of an aesthetic standard has to do with both excellence in filmmaking and the philosophical imagination of the filmmaker. A film of great depth jolts the audience out of an existential slumber; it makes an aesthetic imposition on the dullness of heuristics; it awakens the soul. This is what makes cinema both approachable and ineffable at the same time, and why we keep coming back to the power of the moving image.