Strangely, a horror movie festival is not as straightforward as the name implies. The first I attended was the Fantastic Films Festival in Bradford, England—UNESCO’s first international City of Film in 2009—at the National Media Museum. Despite being home every spring to the world-class Bradford International Film Festival, I went to the National Media Museum expecting to fill my gullet with as much schlock as I could bear. I certainly could have taken in Candyman or that Hammer Films classic, The Satanic Rites of Dracula—instead I saw Carl Theodor Dreyer’s numinous Vampyr, a late silent movie from 1932, projected with a new score played live by Britain’s foremost silent film ensemble, Harmonie Band. Schlock it isn’t. Rarely has a cinematic nightmare been so dreamlike, and Vampyr’s power of psychological suggestion is unmatched in the horror genre except by Let the Right One In and Val Lewton’s improbably named Cat People, one of a string of mid-1940s B movies whose merits are only now being recognized.

Of course, schlock has a time-honored place in the hearts of many moviegoers, especially in the post-Rocky Horror Picture Show and Ed Wood era, and coming at them with a high brow reflects more poorly on the critic than on the movies themselves. Still, I was pleasantly surprised that none of the five new films I saw at the Nevermore Film Festival, held recently in Durham, North Carolina, were of the “so bad it’s good” variety. Some were good, some were bad, but all were made in earnest and asked to be taken seriously. Well, as seriously as one can take a zombie movie set at Christmas time in LA, for example. Held at the Carolina Theatre, a 1926 movie palace and Durham’s best venue for independent film and live music, the Eleventh Annual Nevermore Film Festival made up for its modest size with an impeccable selection of films, from 10-minute shockers to a revival of Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. The new movies I saw, which I will profile here and in a follow-up piece, were strikingly varied, a tribute to the flexibility of horror movie conventions and the kid joy that can be found by playing with them in different circumstances.

Strigoi, directed by British filmmaker Faye Jackson and shot on location in the Romanian village of Podoleni, features a mostly Romanian cast who improbably speak entirely in English. The movie opens cold with a dead old man lying splayed in the foreground, the field he once tended rolling into the background. Mob justice quickly takes over—convinced of their culpability, a group of townspeople including the mayor (Zane Jarcu) and the shifty priest (Dan Popa) execute Constantin (Constantin Barbulescu), a tyrannical ex-Communist Party member with whom the murdered farmer had a land dispute, and his wife (Roxana Guttman). It is up to the audience to decide which of the subsequent shots is more unsettling, Constantin’s blood running into the shallow grave that has been dug for him, or the mob looting the couple’s house as jaunty gypsy folk plays over their glee.

The perspective shifts to Vlad (the affable Catalin Paraschiv), a medical school dropout in a family of doctors who has returned home after an unlucky period living in Italy. Now staying with his grandfather (the gnomish Rudi Rosenfeld, straight from Waiting for Godot central casting)—who pipes up only to blame the theft of their last cigarettes on the communists and the gypsies—Vlad’s idle curiosity is piqued by the farmer’s death. Vlad questions the mourning party about the mysterious wounds in the farmer’s neck, and has about as much success as you’d imagine he would have talking to five men gathered around the coffin using the excuse to get lousy drunk. He then finds himself crisscrossing the village looking for answers. When he walks through an unnervingly beautiful silver fog toward the dead ex-Party member’s house, only to be greeted at the door by his dead wife, Vlad walks straight into a vampire movie.

Strigoi predictability skirts by hewing close to Romanian, rather than Hollywood, folklore about the undead. You’re never quite clear on how somebody becomes a vampire—but nearly everyone in the movie becomes one anyway—and these vampires are more likely to show up in the middle of the afternoon and eat all the food in your refrigerator than stalk you across a lonely graveyard. Structurally, the movie resembles film noir more than horror. The deeper Vlad delves into his own connection to the vampires, and probes into the corrupt way the land was divided up after the end of communal ownership during communism, he finds he can trust fewer and fewer of the people he grew up around. As it develops, somewhat slowly in parts, Strigoi bears a resemblance to The Big Sleep, with its main character worn down by outrageous circumstances and distrusting everyone around him, searching for answers that may not exist. However, Strigoi’s vein of absurdist humor keeps the proceedings from getting too bleak, as in the scene when Vlad warns his grandfather to stop sucking his blood while he sleeps. “It’s my blood,” the grandfather impassively replies, “I gave it to you.” Shot with an eye for local color by cinematographer Kathinka Minthe, its black humor and noir sensibility make Strigoi a vital contribution to the genre, especially given a recent run of less-than-glittering vampire movies.

Bonnie and Clyde vs. Dracula could have been an interesting contribution to its genre if it had picked one of its two genres and stuck with it. In the case of Strigoi and other successful genre-melding movies, even an unlikely combination can graft new life onto an old formula. Less successful combinations only lead to confused expectations and a frustrated audience. As its brilliant title suggests, Bonnie and Clyde vs. Dracula attempts to integrate gangsters into the campier variety of vampire movies, using pulp comic glee as the emulsifier. Would that it could have lived up to the title. The movie opens with an entertaining parlor trick: we watch as a grifter and his moll try to knock over a farmhouse—Bonnie and Clyde, I presume?—only to watch them get wasted by a tommy gun, the more famous couple having gotten there first. Just by the look of them you can tell they’re the real deal. Bonnie’s (Tiffany Shepis) too-dark red lipstick looks as if it’s over-correcting for how dark lipstick looks in black-and-white pictures, and Clyde (Trent Haaga) exudes oily bravado, putting the dirty in the martini.

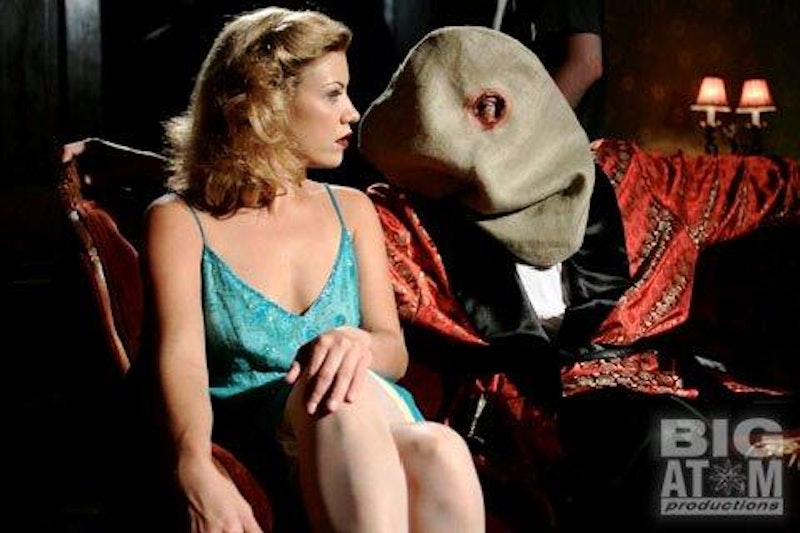

What follows is really two movies; the filmmakers only decide to take up the brilliantly campy promise of the title in the final act. In one, Bonnie and Clyde carve their way along back roads from one job to the next, saying things are going “swell” when they manage to rob someone of their “spinach.” Clyde remains fairly mawkish, but Bonnie has moments of real animal charm. After she kills a farmhand for interrupting them as they smoke a “reefer,” she sways back and forth with maniacal glee, looking as if she might be thanking the Academy if her dress weren’t spattered with blood. Meanwhile, Dracula is finishing up his long con, being resurrected by the mad Dr. Loveless (Allen Lowman), whose disfigured face is covered by a burlap sack, assisted by his charmingly hapless sister Annabel (Jennifer Friend, director Timothy Friend’s wife). Annabel was described by Joe Allen, the producer who introduced the screening, as a sort of funny, updated Dorothy, and she does get a lot of laughs. But unfortunately her Oz is a jumble of genre conventions all thrown together. One of Bonnie and Clyde’s co-conspirators is wounded when they try to rob a truck, and the duo wind up at Dr. Loveless’ mansion to ask for help. Yes, the connection between the plots is as tangential as that. No, none of it is very scary. All of this could have been fun if I had gotten a better idea of which carnival ride I was on, but Bonnie and Clyde vs. Dracula mostly left me feeling kind of nauseous.

Next: Zombies and demons and … Minnesota? Oh my.