The recently released documentary Muscle Shoals takes its title from the town in Alabama famous for its music: Rick Hall’s FAME studio—and the 3614 Jackson Highway facility that splintered off from Hall’s operation—helped to craft a number of hits in soul, rock, and blues, especially in the second half of the 1960s and the first half of the 70s. As a celebration of a history, Muscle Shoals presents a triumphant account of the music scene, but also a simplified one. The film may be too fond of the Muscle Shoals sound—and Hall—to present a complete and informative picture of what went in to making it.

Muscle Shoals follows FAME (Florida Alabama Music Enterprises) from its inception, when Rick Hall partnered up with Tom Stafford and Billy Sherrill and bought a space above a drugstore to record music and write songs. Here Hall managed to earn a hit with Arthur Alexander’s “You Better Move On.” Not long after that song was a success, the musicians who played on it left Alabama and headed to Nashville, and Hall soon fell out with Stafford and Sherrill and built a new studio in the fall of 1962.

He roped in a new crew of musicians as well, most of whom were white, which caused consternation when they became legendary for their bottom-heavy grooves. Apparently, Paul Simon once called up and asked to borrow the black guys who played on the Staples Singers’ “I’ll Take You There,” only to find out that the rhythm section was white. Jimmy Hughes’ “Steal Away” was the first hit at the new location; soon Hall and co. were cranking out soul for big-name heavy-hitters like Aretha Franklin and Wilson Pickett.

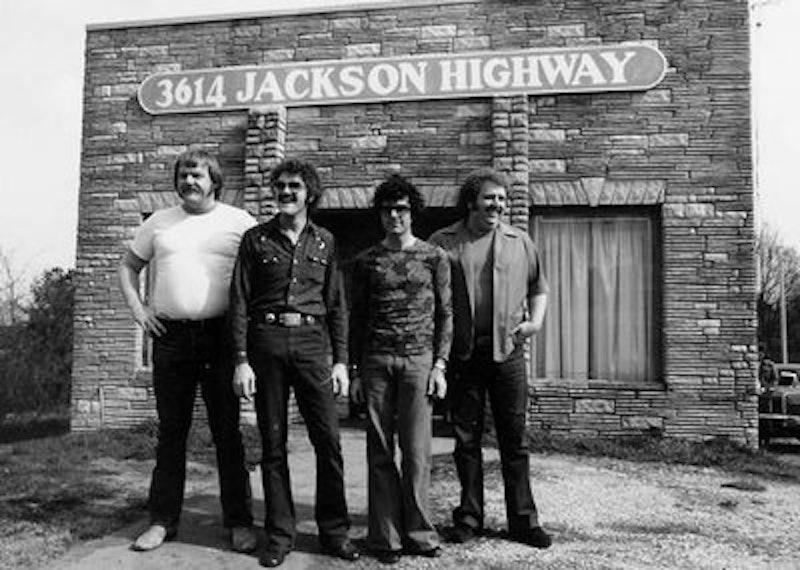

Hall’s core crew of musicians left to start their rival studio, Muscle Shoals Sound, located at 3614 Jackson Highway, in 1969. The movie keeps track of the two studios’ activities into the 70s, when both were still flourishing. Since Hall ran FAME, the movie is as much the story of him as it is the Southern soul and rock his studio and its offshoots became known for.

This documentary is not the only story of Muscle Shoals. Peter Guralnick wrote Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm And Blues And The Southern Dream Of Freedom in 1986, which investigated the history of Southern soul and devoted several sections to Muscle Shoals. History books operate under very different rules than documentaries, able to delve deeply into texture and complexity without worrying about time constraints. Some of the adjustments made by any documentary are necessary, since each minute counts. But if we can believe Guralnick’s account, the movie’s celebration of the sound sidesteps some of the conflict that surrounded that sound’s creation.

Hall got great music out of his studio; he also paid rock bottom for it, which is why the musicians kept leaving him. In his book, Guralnick rejoices in the music, but also details the business angle: Hall had “a tight working band that would play behind the singer and accept union minimum for a simple session, no matter how long cutting the session actually took…” He “had no label roster” except the singer Jimmy Hughes, and he only had a single “salaried employee[s].”

This was one of the reasons that Jerry Wexler, a veteran of the New York music industry and a big-shot at Atlantic records, came knocking after destroying his relationship with Stax. With Hall, Wexler could pay little and earn big profits on the Southern R&B sound. The first number one hit for Hall, Percy Sledge’s “When A Man Loves A Woman,” “was neither recorded by Rick Hall nor put out on the Fame label,” according to Guralnick. But “Rick played a major role in its release and reaped most of the benefits,” as did Wexler. The movie doesn’t go far enough in pointing out that both men were masters of exploitation: this was job outsourcing, R&B style. Did the musicians make some decent money off their work? The film doesn’t tell us. The Muscle Shoals boys were “local people” making timeless soul hits, but those hits were big money for someone.

Muscle Shoals spends a lot of time marveling at its subject, often with stock language. The movie opens with the phrase, “Magic is the word that comes to mind,” and people appear on screen talking about the mystical properties of sound and place. Bono—who had no connection to Muscle Shoals whatsoever—pops up repeatedly, noting that great music often emanates from locations near rivers. (Perhaps this is because American towns are usually built around rivers?)

But Bono’s not the only person heaping rhetorical nothings. We hear that Muscle Shoals is “an enigma,” and that the music produced there is music from the gut or heart. We don’t hear much about the factors that helped create the sound, other than a brief mention of the advanced technology FAME used. There’s a suggestion that Jimi Hendrix changed music in important ways at the end of the 60s; no one says how. After FAME and Muscle Shoals Studio split, Muscle Shoals Studio seemed to traffic mainly in white performers—Lynyrd Skynyrd, The Rolling Stones, Paul Simon, Rod Stewart—while Hall continued to work with black singers like Candi Staton and Joe Tex. This seems interesting, but it’s ignored.

One of the things that makes Southern soul valuable in a different way than its Northern counterpart is that it’s unmediated, very close; the production doesn’t add distance between the listener and the singer in a way that it might on a record from Detroit or Philadelphia. Muscle Shoals likes long, cinematic shots of the rivers, swamps, and fields of sunflowers near the studio, the nature that bleeds into the music. These images are undeniably pretty. But they are the cinematic equivalent of the musical frills and flourishes that Hall and his musicians eschewed in favor of simple melodies and a thick back beat. Celebrating Muscle Shoals is important, but smoothing the complexity of the story doesn’t do the place—or the sound—justice.