By the time my family moved to Baltimore in the summer of 2003, our moviegoing habits and tastes were fixed: at least once or twice every weekend, every rating and genre other than horror (a real blindspot before a few years ago), matinees at the Senator and Charles Theaters, the Rotunda Cinematheque, AMC Towson Commons and White Marsh (the Hunt Valley Regal was a scuzzy backup), and reading all of the entertainment press. But it was jarring to discover that The Baltimore Sun didn’t print movie showtimes like every daily paper in New York, and while we weren’t in a desert, Baltimore’s theater lineup hasn’t changed much at all since 1999 at the earliest, when George Figgs’ Orpheum in Fells Point closed. In the nearly 20 years I’ve lived here, I’ve seen hundreds upon hundreds of movies at the Charles, far more than any theater I went to growing up in Manhattan. I may be able to walk around the UA Union Square 14 in my mind, I was only a regular for seven or eight years. The Charles still feels like a somewhat recent addition to my life.

Gus Van Sant’s Elephant came out in October 2003, and along with Mystic River, it’s the first movie I saw at the Charles. We’d lived in Baltimore for four months, but all the movies I remember from before then were at the Senator (Hulk, Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines, Seabiscuit) or the AMC Towson Commons (The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Matchstick Men, Legally Blonde 2: Red, White & Blonde) or the Rotunda (Buffalo Soldiers, House of Sand and Fog, Kill Bill: Volume 1). The trailer was an exclusive on the Apple website, and I watched it hundreds of times on there, along with the trailers for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Kill Bill: Volume 2, and I Heart Huckabees. It’s still a remarkable trailer, understated but powerful and evocative without ever even approaching cloying or exploitative.

Elephant was developed by Diane Keaton, who commissioned a script by performance art fraud/prankster J.T. LeRoy, which was thankfully thrown out by Van Sant, who was in the middle of his “Death trilogy,” with the superb Gerry behind him and the minor Kurt Cobain sketch Last Days coming in 2005. Elephant was about Columbine, but not by name; unlike 9/11, there was no footage of the actual massacre that day, just blurry security cameras and kids running away; unlike 9/11, a film about Columbine could also be about every school shooting, and every school in America; unlike 9/11, it hasn’t produced a major work in response. A film as much about 9/11 as Elephant is about Columbine would just be World Trade Center or United 93 over again, both 2006 perfunctory dramatizations of an event that couldn’t be topped dramatically. For the first time in the history of American cinema, it couldn’t absorb and enlarge a tragedy dramatically—even the Holocaust yielded dozens of well-known narrative films. I’m convinced the reason there hasn’t, and never will be, a narrative film of 9/11 is that the actual news footage of that day is impossible to “outdo.” It will always be more astonishing.

And unlike 9/11, I wasn’t effected by Columbine. I don’t even remember it happening, less than a month before the release of Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace. I didn’t start paying attention to the news until 2000 or so, but after 2001 it was constant. I was paranoid about school shootings throughout early-middle school, a fear based on nothing but the reality of Columbine, and other less-documented instances in the past. I’d no idea that I was living in a decade-long oasis where school shootings really did take a break, without resuming at full speed in the early-2010s, when I was out of high school. The idea of seeing Elephant wasn’t any more complex than seeing a cool looking new movie about a contraband, violent, and adult subject. It was a cool-looking art movie in the first year that I started going to art houses. It was on the menu.

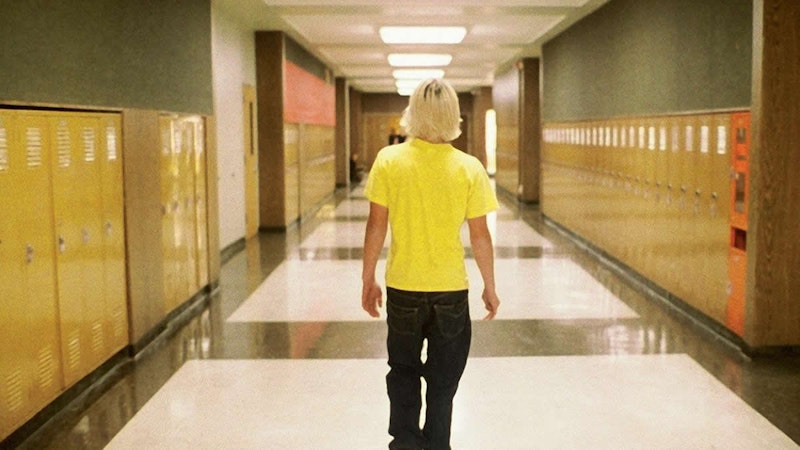

Van Sant’s film is a masterpiece, his best by a long shot, and it remains one of the best American films of the 21st century so far. The only professional actor of note in the cast is Timothy Bottoms, who plays the drunk father of the mop-headed bleach blond boy we follow for a lot of the movie, one of the few who survives. Van Sant allows characters the time to walk and talk and go about their day in real time, using real high school students with good instincts who could improvise dialogue. It’s a chilling movie from the beginning, no music besides Beethoven’s “Für Elise,” and nothing else to tell us how to feel or what to expect. The camera moves indifferently, and stays wide, or focused, often omitting huge amounts of information. But this isn’t Nashville, nor a way-out-there arty “investigation” of a mass death event like Hiroshima, mon amour—Elephant is photographed like a Chantal Akerman movie, and though I wouldn’t see her work for another decade, the way Elephant moved and was photographed, with the camera as much a character as anyone else, struck me and stuck with me for years until I re-watched it for the first time in 2018, when I found it even more powerful and enduring.

I saw that movie with my dad, like Kill Bill: Volume 1 a week or two earlier. Although I saw R-rated movies in 2002, this was the first year anything was available to me, and while the violence in Kill Bill was exhilarating, it wasn’t foreign or mind-blowing; the movie was, but the fountains of blood and hundreds of limbs were cartoonish. I was years past learning that this kind of violence wasn’t anywhere close to real death. Elephant is about real death. I’ll never forget the close-up shot of a girl in the library with the back of her brains blown out, her face a grim mask of raspberry mush and a droopy final sulk, a slow sink before crumpling to the ground. It’s by far the most explicit shot in the film, and while we do see other students and teachers get blown apart, it’s in wide shot, and recognizable as something you’d see in a movie. That close-up still isn’t.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith