It was the early-1980s, and I was in college surrounded by Reagan pods. There had been more intellectual and psychic exploration in Glen Burnie High than was to be found in the dorms of College Park, MD., where on weekends missiles of half-full and unopened beer cans and bottles launched regularly from all windows of every floor.

One of the few lights of this period was an intense teacher (he looked like a speed-wrecked John Denver) who taught a “Beat Literature” course. He disparaged us for being so much more staid than previous classes. “A few years ago I had kids that would show up wearing bathrobes high on LSD!”

Once a year near spring, the two college friends who I made music with (and kept me from applying Exacto knives to blood vessels while Leonard Cohen sang “Songs of Love & Hate”) would have a “Beat Week” inspired by our teacher and our desperation. Ditch studies more than usual, make and listen to as much music as possible, scribble stuff down, and avoid sleep.

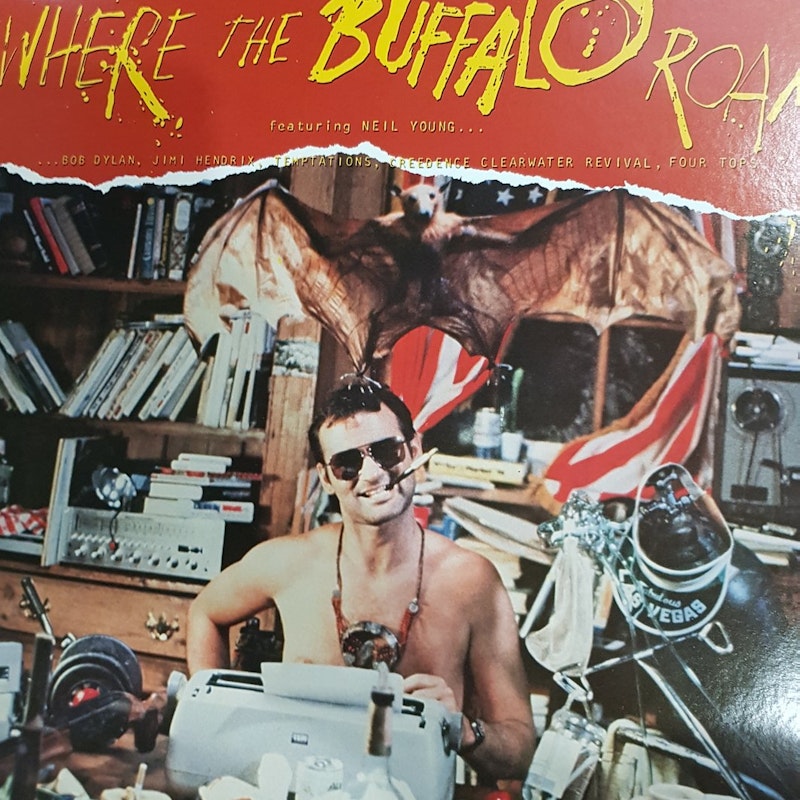

I haven't read Hunter S. Thompson in over a decade, but I believed him when he said, "He who makes a beast of himself relieves himself the pain of being a man”—as a late teen and early-twentysomething. I was white-knuckling it through anxiety and depression, and the elevated everyday horror of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas inspired me. With that in mind, I planned a Beat Week hitchhiking trip that would eventually end at my friend Rebecca’s place, and an outing to see Where the Buffalo Roam, which I hadn't read any reviews of.

After spending a nearly sleepless night up in a tree and later on pine needles beneath the tree, I walked a few miles to Rebecca's in the morning. We then took part in early-afternoon wine and weed, filling ourselves with excitement for our excursion into the world outside.

Pushing open the heavy theater doors into a dark immersive womb smelling of popcorn and cool air over concrete, we clutched each other in anticipation and with the heightened paranoia of introverts who shouldn’t smoke so much weed. Though they started the same year as Where The Buffalo Roam’s release in 1980, I hadn’t heard Einsturzende Neubauten—the closest I’d come to an aural maelstrom was The Pop Group, but if I had I would’ve had a context for what we heard in the theater. Ferocious clanging, battering waves of reverb, sparking drills. Jagged shadows appeared on the gray screen and were quickly snuffed out. Glimpses of fragments of shadow arms and slices of head. “Oh my god, this is amazing,” we both stage-whispered clutching each other’s arms. I was witnessing a cinematic breakthrough with one of my favorite people, in Glen Burnie of all places, on little sleep and high as a kite.

We crept and staggered along the backs of the back row seating, too engaged to hurry to a seat. Five minutes after we’d entered the theater and had our minds blown, the lights snapped back on, revealing the mundane scene before us, making us feel like cockroaches caught in God’s kitchen at midnight. Two or three bored repairman dragged their tools and some cables from out behind the movie screen and shut it all in some back room.

Stunned, we took seats and witnessed a thoroughly mediocre take on the exploits of Hunter S. Thompson. Bill Murray chilling it to Hawaiian shirt degrees and it was the basically the same performance he gave many years later as FDR in Hyde Park on the Hudson. To me, Thompson was far darker than Murray, Johnny Depp or their directors portrayed him. All that ether, whiskey, weed, acid, amphetamine, adrenaline, and whatever else was in the kitchen sink stew wasn’t just sport for an athlete of the brain, a wild party pirate: he was seeking while also running, hiding, and fearing.

Many years after seeing Where the Buffalo Roam, I saw Thompson speak at a bar in Baltimore on the occasion of a new book of essays. And “speaking” is overselling what took place. His tongue was rubber, rolling around in electric wool blankets. Trying to follow his thoughts gave way to trying to thread sentences from him to hoping to catch a word or two to finally just absorbing the presence of the person who spoke to my inner writhing and twitching.

But the raw nerve art happening that my friend and I had in that five minutes of darkened theater under repair couldn’t be taken from us. We shared an elevated artistic experience that was 90 percent our own damaged making.