Next year will be 50 years since the release of Richard Fleischer’s Mandingo, or more accurately Dino De Laurentiis’ Mandingo. Only a producer as rich and insane as Laurentiis had the audacity to make two big budget exploitation movies about black American slavery, both smuggled into MGM and made with studio tools and money. Mandingo is a great American movie, known more for its title than itself; the unrelenting brutality of the film, surely a fraction of the reality of the antebellum South, is paired with our own disbelief and nationalist cognitive dissonance. There have been many movies about black American slavery in the last 50 years, some bigger than others, some more brutal than others, but Mandingo and Drum predate and tower above them all.

Maybe not Drum, the even lesser-known 1976 sequel. The same year that Laurentiis made another King Kong, he made another Mandingo and got another Hollywood journeyman to direct it: Burt Kennedy. He walked off the movie four days in, disgusted with the script; recent AFI graduate and Roger Corman mentee Steve Carver took over. According to him, it was an exercise in filmmaking, an opportunity to work on a movie with a crew of 160 rather than 20. In August 2020, Carver told Flashback Files that, “Dino said to me: You worked with Roger Corman? You did lots of tits and ass? I want exactly that! And [producer] Ralph Serpe kept telling me: Try to get as much as you can! And I did. I went up to every one of the actors and said: You signed the contract with Dino. You said you would do the nudity. Except for Pam Grier who had it in her contract that I could shoot her up until her breasts. So, of course, I respected that. But Isela Vega would walk around the set totally nude! She didn’t care.”

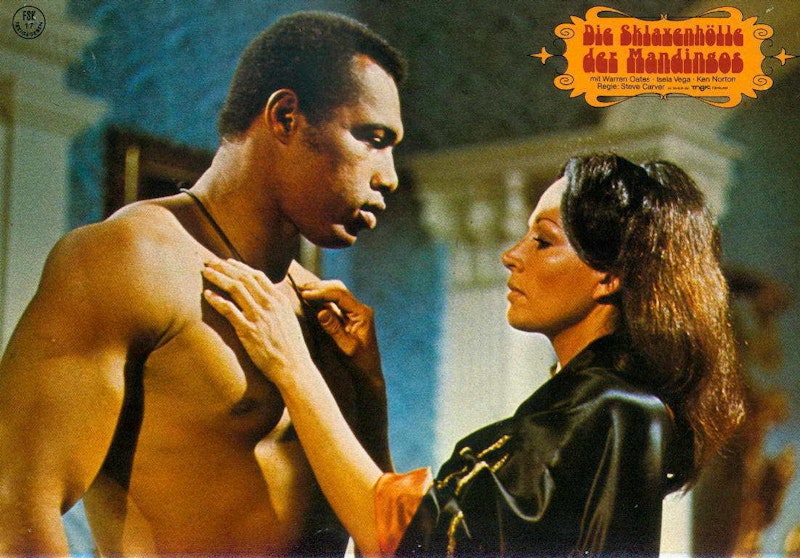

Drum, like most sequels, is a bit dissonant and strange to begin with, but just about everything contributing to that are what make it interesting: another great cast full of New World regulars like Grier and Rainbeaux Smith, Peckinpah favorites Isela Vega and Warren Oates (in the James Mason role), and actors returning from Mandingo like Ken Norton, Brenda Sykes, and Lillian Hayman. Unlike Mandingo, it’s over-lit and studio-bound, swapping the sinister sun and vast, empty, and dirty plantation of the first film with a lot of night scenes and a ton of extras (it’s not Goodbye, Uncle Tom, but this was a Laurentiis production). Norman Wexler returned to adapt Kyle Onstott’s novel, though it was surely chopped and spiced up during shooting; Lucien Ballard shot Drum, but it might as well be anybody walking the lots at MGM—the photography in Drum never rises to the material, especially compared to Richard H. Kline’s work on Mandingo.

Yaphet Kotto appears in a major supporting role, unhappily: “Everybody had fun on that picture, except for Yaphet Kotto. I don’t know what brought it out, but he had a real attitude about the content of the script. Also, there was a competition between him and Kenny [Norton]. First, he wanted as big a Winnebago as Kenny’s. He refused to act until that happened. I’ll tell you, the Winnebago was the size of a small house. Dino had to intervene.” Yeah, I can’t imagine what made 37-year-old Kotto have an “attitude” about playing a slave in an exploitation movie because he needed the work. Kotto might be best known for Alien, but in the 1960s and early-1970s he was, like many black actors, stuck in a certain kind of role in a certain kind of movie. His biggest role by then was the voodoo villain in Live and Let Die, and now, three years after being blown up and bulged eyed by Roger Moore, he’s introduced getting his face beat in by Norton.

Work is work, but by that point, Kotto had been in Friday Foster, The Liberation of L.B. Jones, Truck Turner, and Across 110th Street, films that exploited black glamor and heroism; they were violent and crass, but Grier, Richard Roundtree, and Fred Williamson played heroes, not slaves. They weren’t boiled alive at the end, they got the girl/guy and lived happily ever after! Maybe that’s why Quentin Tarantino loves Drum almost as much as Mandingo; besides Caligula level T&A, the climax of the film breaks the rules by giving the audience everything they want. Even years after self-censorship ended in Hollywood, rarely were women shot in cold blood on screen—if you remember nothing else from The Wild Bunch, you remember William Holden shot-gunning a woman in the stomach after calling her a “BITCH!” Here, Peckinpah favorite Isela Vega is cornered by some of the slaves she tormented, and while there’s a moment of hesitation, they finally pull the trigger, and we watch her slump against the door, wide-eyed and dead. Death is ordinary, final, ugly and sick like this, even a righteous revenge.

Carver and Laurentiis’ sensibilities, combined with the over-lit MGM atmosphere, create something, if not as powerful as Mandingo, still unique even among 1970s American exploitation films. All of the bad guys and girls die bad; Django Unchained is the only other modern Hollywood movie to deal with black American slavery not only as an “adventure film” but as riotous revenge as well. Mandingo is one of the few films that Jonathan Rosenbaum and Tarantino line up on, and for the same reasons. Drum isn’t trying to be important—Drum only tries to be entertaining and extreme. Carver says he wanted to show “the audacity of slavery,” and he does in his own way. Movies like this are rare in America, and it makes sense that a foreign producer like Laurentiis would be the one to dare to make them.

What a time to be a journeyman director—coming off of Corman co-production The Arena, Carver was called in to replace Kennedy, who didn’t hold it against him, and got to work with some of the greatest technicians and tools in the history of commercial filmmaking. This was also an era when legends still stood, some still working; asked if he ever saw Fellini, Carver says, “Yeah, Federico was so funny. He didn’t speak any English, but he would come during his lunch break and sit beside me, next to the camera. He loved to watch the big breasted girls fight the gladiators. Then I would go over to his set and watch him shoot Amarcord. It was great.”)

Sounds like it, sho’ does.

—Follow Nicky Otis Smith on Twitter and Instagram: @nickyotissmith