If you look up Werner Herzog’s 1971 documentary, Land of Silence and Darkness, the internet will spit out a rather Herzogian description: “edifying, touching, and bleak.” One could describe Werner Herzog in such a way, as well as Land of Silence and Darkness. The film’s written, produced, and directed by Herzog (missing is Herzog’s unique narration, and in this case it was provided by Rolf Illig), and tells a story of a German woman, Fini Straubinger, who became deaf and blind early in her life.

In the film, Straubinger visits people with the same affliction, and the narrative unfolds through her encounters with others. Straubinger became deaf and blind gradually. When she was nine, she fell off the stairs, and this caused various health issues. She slowly lost sight and hearing. She was mostly neglected by her family, at least emotionally and psychologically. Straubinger found solace in God and religion, but that wasn’t enough to combat the loneliness she felt throughout most of her life.

“People seem to think that when you are deaf, you hear nothing, absolute silence… Or when you are blind, you see darkness,” says Straubinger. But this isn’t true. The sound of silence is “droning,” and the seeing involves flickering colors. Both have no concrete meaning attached to it, and hence Straubinger’s world is depressingly and nihilistically abstract. But Straubinger’s driven to find meaning in life.

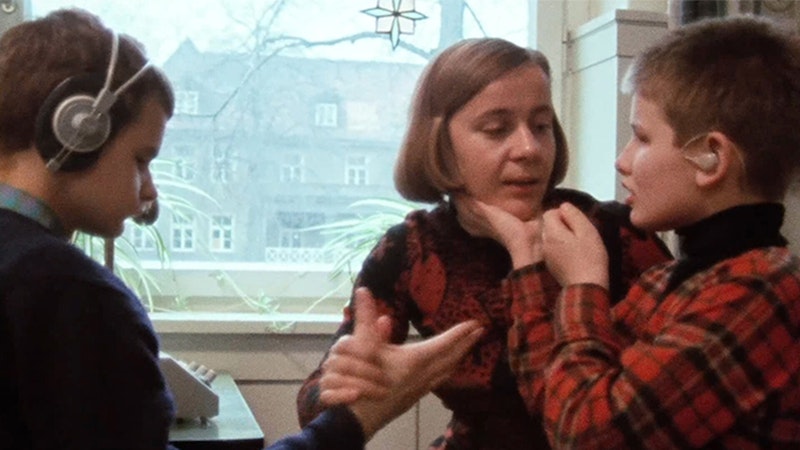

As if subconsciously enacting Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy, Straubinger enters into encounters with others in her attempt to give them what they seek the most: recognition. We witness her own birthday party. As guests are coming in, we realize that most are deaf and blind. They require “translators,” companions who have one affliction but not both. Some are able to read lips, others touch lips with their hands to find out the meaning of words. Straubinger communicates with hands, using a kind of Morse code to piece the words together.

Straubinger can function mostly on her own, but some people she visits are at the mercy of others. Often, they’re forgotten and neglected either by their family or the health and social system. One woman was entirely discarded only to end up in a neurological clinic—not exactly the right fit. Herzog’s camera focuses on these human faces, at once frozen and speeding along the existential lost highway toward nothing. Yet, they’re all somehow aware of his camera and do their best to remain dignified. In all of the disorder, they’re searching for the inner humanity.

Some people featured in the documentary became deaf and blind as a result of illness or an accident. Others were born that way. It’s difficult to watch the children suffer. Herzog’s uniqueness lies in his rejection of sentimentalism, and this is no exception. There’s bleakness, yet Herzog’s vision and his own openness to such encounters renders his work hopeful.

One boy struggles greatly. He’s deaf and blind, but is taken care of, living in a facility. His caretaker describes the progression of the boy’s betterment. It’s a long journey but it’s not without meaning or even destination. In one scene, the boy’s trying to get into a pool. He used to be afraid of the water but now appears to be more comfortable. His caretaker wants him to do as many tasks as possible of his own volition. Full independence is impossible but small achievements every day are and they do happen. The man encourages the boy to keep going. There’s a great love and compassion in this relationship, as the man teaches the boy to be.

Perhaps the most difficult encounter Straubinger has is with a boy named Vladimir. He’s deaf and blind, and never learned to walk. His father was the only one who didn’t abandon him but had no means or knowledge to help his son. Vladimir was never taught to walk or properly eat. Here, we see him move awkwardly, touching his head, his arms and legs, trying to find himself.

Straubinger sits with him, and begins to touch his shoulders and face. Vladimir smiles slightly. A radio’s brought in and Vladimir is holding it in his hands, clutching at it like an innocent child would a teddy bear. His face changes. He expresses giddiness at feeling the vibrations of music coming from the radio. Life is possible.

Every documentary filmmaker has some kind of agenda, or at the very least, an intention. Herzog clearly wants these forgotten people to remain in someone’s memory. Yet he never imposes a meaning (whether of life, deaf and blind people, or the film itself). The dignity of these people is there not because Herzog is trying to create it but because he’s not a selfish voyeur. He sees them and their daily struggle, as well as small but meaningful triumphs. He sees their joys and their loneliness. (If Diane Arbus was taking photographs of these people, they’d metamorphose into freaks, but in Herzog’s hands, they’re humans, worthy of love.)

There’s one aspect that binds Land of Silence and Darkness together; the relationship between an encounter and mystery of being. Even an encounter with a tree (seen at the end of the film) builds a relationship between a deaf/blind man and nature. The touch itself reverberates back into a man’s being, and he feels recognized.

Many caretakers in the film make one repeated remark: we don’t know fully how the deaf and the blind feel. They remain a mystery to us, and perhaps even to themselves. But the mystery’s not an obstacle to an encounter. On the contrary, it’s an invitation to a recognition of the human face.